(Updated at 2:30 p.m.) In the latest episode of PBS’ Finding Your Roots, historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. helped guide six-time Tony-winner Audra McDonald on a tour of her family lineage — a journey that led her to a golf club in Arlington.

McDonald’s trip through her family tree started with her maternal grandfather, whom she credited as a major influencing force on her life. Her grandfather, Thomas Hardy Jones, was described by McDonald as “born into the depths of the Jim Crow era” but managing to build a respected career as an educator in historically Black institutions.

Her awareness of her mother’s paternal lineage ended there, but Gates took McDonald further to meet her great-grandfather: Clarence Jones.

“After stints as a miner and chauffeur, Clarence supported his family and paid for his son’s education by working in a locker room in a segregated golf club in Arlington, Virginia, where it seems he somehow managed to thrive,” Gates said.

Clarence Jones worked at Washington Golf & Country Club, the first golf club in Virginia and a prestigious regional institution that counted presidents Wilson, Taft and Harding as active members.

The club was segregated, however, and Clarence Jones worked at the club but could never play there. Only starting in the mid-1970s were Black and Jewish applicants granted membership, according to a book by former Northern Virginia Sun publisher Herman Obermayer.

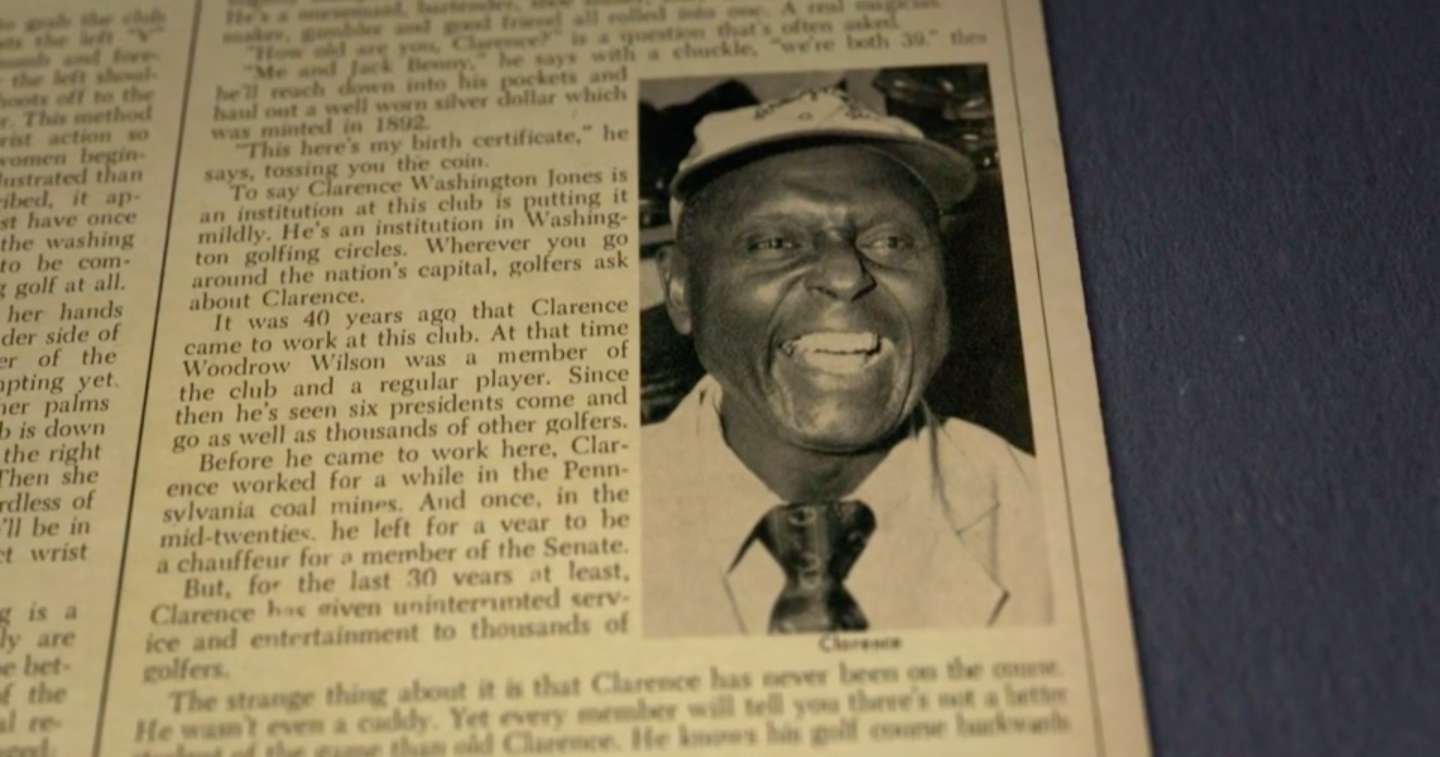

Even so, Gates’ team found a newspaper article from the time that profiled Jones, in which he was described as indispensable and well-loved by the golfing community.

“[He is a] shoe shiner, story teller, match-maker, gambler and good friend all rolled into one,” Gates read from the newspaper. “Wherever you go around the nation’s capital, golfers ask about Clarence.”

McDonald said many of those traits described in Clarence Jones were passed down to his son, her grandfather.

Records showed that Clarence Jones’ parents were both born in D.C. shortly after the Civil War, but the paper trail ended there as their parents were likely enslaved.

McDonald said that learning about her great-grandfather was bittersweet knowing that he was held back by the racist institutions of his era.

“There’s a part of me that’s amazed and proud of my great-grandfather,” McDonald said, “but a part that hurts for him too.”