Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

The H-B Woodlawn Secondary Program is housed today at 1601 Wilson Boulevard, a hundred-million-dollar building located not far from the place in Rosslyn where, a little over a century ago, a posse fired at a fleeing Black man because white landowners wanted to make the county more profitable for real-estate development.

But when I was a student at the H-B Woodlawn Secondary Program, it was housed at 4100 Vacation Lane. That building had once been Stratford Junior High School, and on February 2nd, 1959, it was the first school in the Commonwealth of Virginia to be racially integrated.

When I skipped class for pizza, my slices came from the same shopping strip where, in 1960, Howard University students faced off against the American Nazi Party in sit-ins that desegregated eateries across Arlington, Alexandria, and Fairfax. We studied that history with pride during my four years at H-B. We may even have studied the 1968 Supreme Court decision that made racially-restrictive covenants — Lyon’s bluntest tool — illegal across the nation.

But somehow, despite Arlington’s proud history of civil rights activism, my H-B graduating class of perhaps 90 students included only three or four who were Black. The number of other racial and ethnic minorities, and of low-income white students, was also disproportionately small. We studied school integration, sit-ins, and voting rights at H-B Woodlawn. What we did not study were the ways that implicitly-racist policies, like exclusive zoning, survived that activism and remain with us today.

This is the sixth part of Lyon’s Legacy, a biweekly series (you can read the whole thing, with citations, here). This series is not intended to claim that Frank Lyon or his developments are uniquely responsible for Arlington’s present problems. Rather, the particular story of Lyon is meant to illustrate the broader history of how economically-exclusive zoning, established a century ago in an atmosphere of white supremacy, still dominates our county and our nation today.

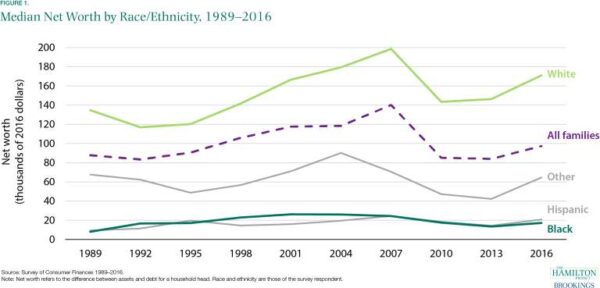

In Frank Lyon’s time, just decades after Emancipation, Black Americans usually — though of course not always — had less money to spend on housing than white Americans did. By creating large lots and banning missing-middle housing, developers of the time ensured that their homes would be so expensive that low-income people, including most Black people, couldn’t afford them.

That was the beginning of a two-handed strategy that keeps Black families out of places like Arlington to this day. With one hand, as we saw two weeks ago, local and federal governments adopted the technique, pioneered by Lyon and his peers across the country, of economic exclusion through car-oriented, low-density land use. With the other, the same governments limited financial and employment opportunities for Black people, trapping many in a cycle of poverty. By the time that explicitly-racist policies were curtailed in the 1960s and ’70s, the damage had been done, and most Black people were priced out of most suburbs.

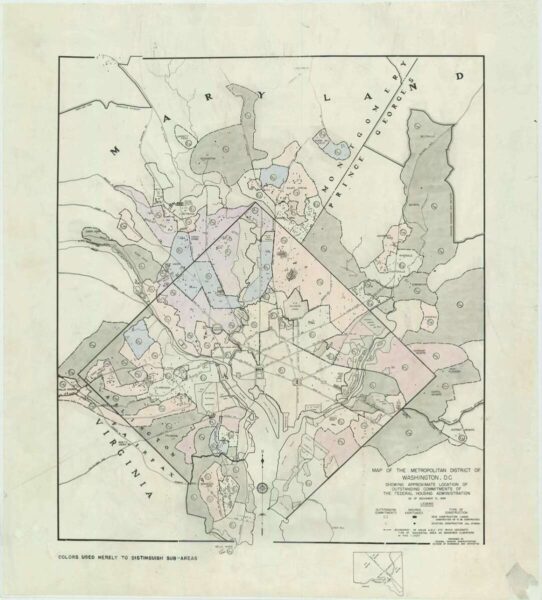

Car-oriented single-family zoning wasn’t the only technique that the federal government, local governments like Arlington, the private sector, and neighbors themselves used to keep Black families out of white neighborhoods. Others included ‘redlining’: the federal government’s refusal to insure mortgages in neighborhoods where Black people lived.

They also included subsidies for all-white neighborhoods, ‘blockbusting’ and ‘steering’ tactics used by realtors, racially-discriminatory and often exploitative lending by banks, the granting of tax-exempt status to discriminatory institutions, and even not-infrequent violence visited upon Black families who dared act upon their legal right to move into white neighborhoods. Some of these continue today. All these techniques kept Black families from building equity through suburban homeownership in the way that white families could.

Nor was housing the only sector in which Black Americans, and other minorities, faced discrimination. An equally-extensive array of obstacles kept them from economic participation more broadly. Before the Civil Rights movement, most banks wouldn’t loan to Black people. When Black people started their own banks, they were sometimes persecuted — most dramatically in the case of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 2021, which killed hundreds and burned ‘Black Wall Street’ to the ground.

Inability to access credit meant that Black people were excluded from the rest of the country’s upward cycle of economic growth. The New Deal and the GI Bill also systematically denied employment to Black Americans, as well as racist employers and state-level employment laws. And discrimination extended beyond employment, into education, healthcare, and politics – all of which had economic impacts. The Civil Rights movement ended most explicit economic racism. But it did not undo the damage.

Black people aren’t the only group to be systematically excluded by expensive housing. Immigrants and refugees often seek opportunity in places like Northern Virginia, but they can’t afford a mortgage because they come from countries that have been systematically underdeveloped by the extractive interventions of wealthier nations — including ours. People of all races who move to our region from disinvested parts of the United States often lack a foothold to buy into Arlington’s prosperity.

But costly, single-family detached houses are still the only legal thing to build in most of our neighborhoods. Our streets and buildings are engineered to give privilege to those already wealthy enough to own cars. In the 1970s, that began to be challenged by Arlington’s ‘Smart Growth’ plan of development around Metrorail stations, which provided for high-rise housing dense enough to be affordable.

Our success was so highly-regarded that Arlington trumps Hong Kong to put a photo at the top of the Wikipedia article for transit-oriented development. But we can’t rest on our laurels. The Smart Growth plan touched barely a tenth of Arlington’s land, leaving the rest in the grasp of exclusionary zoning. Fifty years on, as we run out of land near the Metro stations, demand is running circles around supply and prices are skyrocketing.

The racism of Frank Lyon’s day may no longer be in the letter of our laws, but it is still in our zoning codes, just as it was laid there a century ago when Klansmen raised their flag over Arlington.

This year, with the Missing Middle Housing Study, those zoning codes could change.

D. Taylor Reich is a native of Arlington and a graduate of H-B Woodlawn. They work as a researcher in urban mobility analytics with the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, where their research has been covered by international publications including The Guardian, BBC, and China Daily. Previously, they were a Fulbright scholar in Amman, Jordan. Taylor has served on the Arlington Transportation Commission and the Plan Lee Highway Community Forum.