Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

“A racist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups. An antiracist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial equity between racial groups. By policy, I mean written and unwritten laws, rules, procedures, processes, regulations, and guidelines that govern people. There is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy. Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity between racial groups.”

– Ibram X. Kendi, How To Be An Antiracist

This is the penultimate part of Lyon’s Legacy, a biweekly series on ARLnow (you can read the whole thing, with citations, here). Until now we’ve been looking back into history, trying to understand the part racism played in Arlington’s transformation into a suburb. This time we’ll see what antiracism could do in the transformations of today. This time we’ll face the Missing Middle Housing Study, and you’ll learn what you can do to make your voice heard.

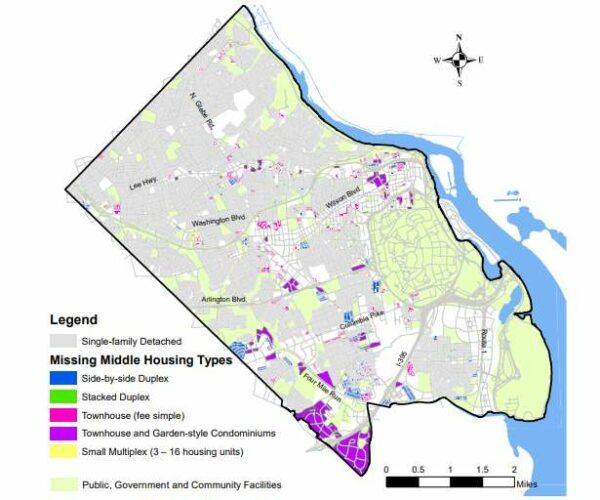

‘Missing-middle’ housing is anything denser than a single-family detached house but smaller than a high-rise tower. The ‘white-washed, one-and-a-half story duplexes’ of the Freedman’s Village were a form of missing-middle housing. So are the rowhomes of Georgetown, the triple-deckers of New England, the five-story canal houses of Amsterdam, the eight-story city blocks of Paris. A century ago, Frank Lyon and people like him made them illegal in Arlington. In most of our county, our zoning still bans them today.

By setting aside three-quarters of our land for single-family homes, our zoning code artificially inflates the supply and deflates the cost of high-end houses, while doing the opposite to apartments and condos. Our zoning code privileges the wealthy.

Over the next two years, the ongoing Missing Middle Housing Study could legalize some forms of more affordable housing. The question is whether it will legalize enough. The math is clear: wealth inequality is so extreme that legalizing duplexes alone won’t make Arlington the inclusive county we say we want to be. We have to legalize apartments.

The median income for Black households in the greater Washington area is about $75,000 per year, while the median income for white households is $124,000. A home is affordable when the sale price is no more than roughly 4.5 times the family’s annual income, so a median-income Black family can afford to buy a home costing up to about $340,000.

Existing houses in Arlington cost an average of $959,000, up by over $100,000 since 2018 alone. But for new single-family detached houses with five or more bedrooms in Arlington, which are by far the most common kind of new house in our county, buyers are willing to pay an average of over $1,600,000. The gap between what Black families can buy and what our zoning code produces, the gap between $340,000 and $1,600,000 — that gap is Lyon’s legacy.

The gap between $340,000 and $1,600,000 is also the first thing we need to know in order to undo Lyon’s legacy. It tells us that duplexes, like the ones in Freedman’s Village, won’t be enough. Half of $1,600,000 is $800,000, and $800,000 is still too much.

So what kind of housing would median Black families be able to afford in Arlington? Assume it costs $2,000,000 per lot to replace an old single-family home with a new missing-middle one. This is almost certainly an underestimate, so it’ll underestimate the density required. $2,000,000 divided by $340,000 is about six. Six is the magic number for the Missing Middle Housing Study. If we make it legal and feasible to build six-unit buildings on any plot, then landowners will be able to build housing that is dense enough to be racially inclusive while also being profitable enough to compete with the demand for single-family homes.

You can see the details in your own neighborhood by using a model I’ve assembled using data from across the county. The economic reality is more complicated, yes, but the model is a first-order place to start.

To make apartments and condos feasible, we have to do more than make them legal. Today, single-family detached houses are required to have ‘setbacks’ — yards in front, in back, and on both sides, and they must have parking spaces. There are also height restrictions. We must remove those onerous requirements. Two years ago, Minneapolis legalized three-unit buildings in every neighborhood. But they didn’t change any setback or parking requirements. The reform didn’t work: you can count the number of new three-unit buildings since then on one hand. In addition to removing setback, parking, and height restrictions, these new buildings must also be legal for anyone to build, without a costly review process: we must have a rezoning rather than a GLUP change.

This kind of zoning isn’t insanity. It won’t tear Arlington apart. Similar reforms have already been adopted in Sacramento, CA and Portland, OR. Many others, including Charlotte, NC, are considering the policy. These cities haven’t transformed overnight, but they’re gradually starting to see more affordable homes being built.

Legalize apartments, anywhere in Arlington. These could include subdivided houses, garages and sheds turned into studios, or new homes built in backyards. They could be mixed-use, with homes above cafes, restaurants, corner stores, or bakeries. Somewhere, neighbors might consolidate their lots to build together. Elsewhere, someone with a large lot might subdivide it, selling their backyard and keeping their home.

People won’t be forced to choose between shoebox apartments in the sky or big homes on big yards, they’ll be able to live comfortably in the middle. Small buildings like these will be the work of local builders who know our county — they’ll be too small for the big national developers to care about. A few decades after we legalize the missing-middle, Arlington won’t just be more racially diverse. Our county will be more diverse, more vibrant, more thriving, more unique in every way.

Legalize apartments, anywhere in Arlington. The change won’t be instant. Most of Arlington’s homeowners could already turn a profit by selling. But people who live here want to stay, and zoning reform won’t change that. But with zoning reform, when an Arlingtonian does move out and their house is torn down, the developer won’t have to build a McMansion to turn a profit. They’ll be able to build something that Arlington’s teachers, firefighters, construction workers, even our janitors might be able to afford instead. Your neighborhood won’t be bulldozed overnight — it will evolve over decades.

There are four common arguments against zoning reform: traffic, schools, flooding, and skepticism. I’ll address each in turn.

“If we build all these new homes,” ask critics, “traffic will be unbearable! Where will they all park?” The answer: We want new neighbors in Arlington. But we don’t want a single new car.

With good planning, density makes traffic get better instead of worse. Between 1996 and 2012, 50,000 people moved to Arlington. In the same period, traffic congestion declined by 5-10%. Arlington successfully integrated transportation and housing along the Metro corridors. We must now do the same in our neighborhoods.

Walkability is the solution. Not just investing in better sidewalks, but building neighborhood retail. Everyone should be able to meet all their daily needs on foot: picking up groceries, getting a haircut, visiting a co-working space. And to get people between neighborhoods and into DC and Fairfax, we’ll use e-bikes in protected lanes; frequent, and eventually rapid, bus transit. To prevent people from driving unless they really have to, we’ll use market-rate on-street pricing for car parking.

Densification would bring more students to our schools. But it would also bring more money. Density increases land values, creating wealth that pays for schools and other services. Arlington derives 50% its present tax revenue from the 11% of the land that lies along Metro corridors. Meanwhile, our low-density areas “enjoy one of the lowest tax burdens in the Washington Metropolitan area.” Dense, inclusive neighborhoods subsidize single-family zones, not the other way around.

Storms have been bad lately. With climate change, they’ll get worse. Zoning reform would eventually result in us losing a lot of our front yards, which seems like a problem for stormwater management – but it’s actually a solution. Grassy yards aren’t actually very good at absorbing floods. Impervious driveways are terrible. With an opportunity to redevelop, we can replace them with biophilic stormwater infrastructure for the 21st century, working with nature instead of against it.

The final objection concerns zoning reform’s ability to create truly affordable housing in Arlington. Critics point at 1.2-million-dollar townhomes, at the high costs of both land and construction, at the white-hot real estate market, at the idea that this kind of upzoning would cause land prices to increase even further.

No matter how many units we can cram on to a lot, they say, those units might never be affordable to the truly low-income. These critics might even be right. It may be that wealth inequality in our country is so extreme that it has become impossible for the market economy to provide realistically-attainable housing for an average family in Arlington County — it might be that the only options are public housing or government subsidy.

But even if these critics are right, it doesn’t follow that zoning reform would not be a good thing. Imagine a condo building replaces a $2 million house in Lyon Park and four units sell for $700,000 each. This would not be affordable to a median-income family. But maybe it would be affordable to a young family whose other option is to renovate a rowhouse in a gentrifying neighborhood of D.C. Or maybe the three new units prevent another acre of farmland in Loudoun from being bulldozed into a subdivision. Densification in Arlington can prevent displacement elsewhere. Let’s not let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

The Missing Middle Housing Study is a multi-year process, and won’t result in any zoning changes until 2023. But one of the most important deadlines of the entire Study will come in just a few days. This Tuesday, June 8th, is the end of the Housing Typologies Feedback Opportunity. This Feedback Opportunity is an online survey that lets you tell the county’s planners what kind of missing-middle housing we should legalize in Arlington. It could determine whether or not multi-unit apartment buildings are even considered for discussion.

As a child in Arlington’s public schools, I was taught to share the things I loved, not to jealously guard them. Missing-middle housing is our chance to share Arlington. The Housing Typologies Feedback Opportunity will be open until Tuesday. This is the opportunity of a generation to shape the future of Arlington — the opportunity to play a part, a century after Frank Lyon, in changing his legacy.

D. Taylor Reich is a native of Arlington and a graduate of H-B Woodlawn. They work as a researcher in urban mobility analytics with the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, where their research has been covered by international publications including The Guardian, BBC, and China Daily. Previously, they were a Fulbright scholar in Amman, Jordan. Taylor has served on the Arlington Transportation Commission and the Plan Lee Highway Community Forum.