Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

I grew up in Arlington because, in the 90s, it was a place where middle-class parents could afford to own a home and raise two children. I loved my childhood here. But because of Arlington’s economically-exclusive zoning laws and their contribution to rising housing prices, I don’t expect to be able to give my kids the same.

This is the eighth and last part of Lyon’s Legacy, a biweekly series on ARLnow. You can read the whole thing, with citations, here.

As I grew up, my family lived in three neighborhoods: Tara-Leeway, Woodland Acres, and Cherrydale. All were wonderful, with lovely neighbors, beautiful parks, friendly schools, and — my favorite — peaceful libraries. But all three are subject to restrictive single-family zoning, prices have skyrocketed, and on my NGO salary I can’t imagine ever being able to afford a home and children in any of them.

Now I am grown enough to see that Arlington has a choice. We can leave our zoning restrictions in place and watch our county turn into an exclusive enclave of the super-rich. Or we can build a few stories taller, turn some car parking into bike lanes, and smile at the kids of the new middle-class family in the apartment next door.

Legalize six-unit apartments on any lot in Arlington. Use the zoning code, not the GLUP. Remove requirements for setbacks and off-street parking. Build bike lanes, bus lanes, schools, and parks to provide for the new residents. Legalize neighborhood retail. Our neighborhoods will not only become more inclusive, they will also become more sustainable, economically productive, safer, socially-connected, and physically and mentally healthy.

Lyon’s changes to our county a century ago were radical. He and men like him utterly transformed Arlington, converting it from farmland to exclusive suburbs. Many things that Lyon did were good: he left us with beautiful parks and charming homes. But he also left us with laws, forged in racism, that have only become more stringently exclusive as housing prices have risen over the last few decades. To expunge racist exclusion from Lyon’s legacy in Arlington, we now must be as bold as he was then.

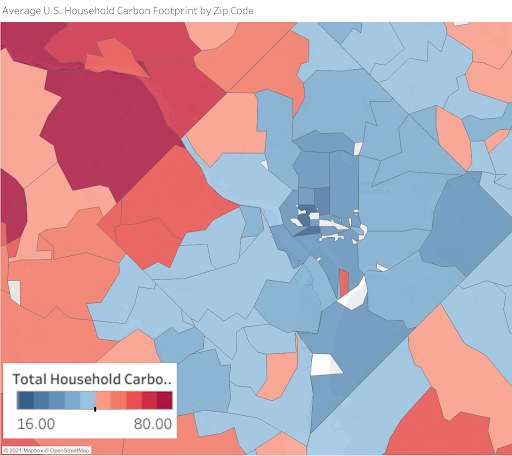

Confronting exclusive zoning, we not only face racial injustice — we face our own contributions to global climate change. Those of us living in Arlington’s northwestern, single-family, economically-exclusive ZIP codes of 22205 and 22207 have the largest carbon footprint in the county, over 60 CO2-equivalent tonnes of greenhouse gas per household per year. Carbon emissions in DC’s ZIP codes of 20001 and 20009 are about half of that. This is largely because people living in walkable neighborhoods drive cars less, but also because it’s more efficient to heat and cool apartments than single-family homes.

Just as with housing affordability, in climate change a compromise is insufficient. Minor increases in density through duplexes or rowhomes will not be enough to overcome Arlington’s car dependence and allow us to live less carbon-intensive lifestyles, doing our part to restrict anthropogenic global warming to 1.5 degrees C. Nor will electric cars, not when their batteries depend on extractive rare-earth mining and electricity from burning coal. If Arlington believed in climate science and in the urgency of the crisis, we would get rid of our garages, not just change what we park in them.

Climate justice is racial justice too. When sea levels rise, it is not places like Arlington that will flood: it is places like Kolkata and Dhaka, Lagos and Abidjan. Even within the United States, as the Climate Justice Alliance holds, we live in a regime of “environmental racism where communities of color and low-income communities have been (and continue to be) disproportionately exposed to and negatively impacted by hazardous pollution and industrial practices.”

By reducing carbon emissions, zoning reform in Arlington will change what our county means to the rest of the world. It will also change what our county means to us. But Arlington is already changing. Today’s Arlington could not be home to my children the way it was home to me. Our county is changing, and there’s no stopping what can’t be stopped. We must ask: what is more important to the soul of Arlington? For it to be a place where a middle-class family can raise their children? Or for every home to have a yard and a garage? We can no longer have both.

I think the soul of Arlington can live in an apartment just as well as it can live in a detached house. But I do not think that the soul of Arlington can live in a 2-million-dollar McMansion.

The soul of Arlington is in the Stratford integration, the Cherrydale sit-ins, in the family stories still told about Queen City or Hall’s Hill. The soul of Arlington is in the public school teachers like those who taught me my first lessons of justice — teachers in H-B Woodlawn’s new building as well as its old one. The soul of Arlington is in our proud punk music heritage, the memories of Dischord and Positive Force. But activists, teachers, and musicians can’t afford to live here anymore.

Arlington is changing, but we can choose how we change. We can reform our zoning code and watch our county’s physical body rebuild, flourish, and manifest justice. Or we can leave the code in place and watch housing prices rise, watch as our body of buildings and streets maintains its facade and our soul withers.

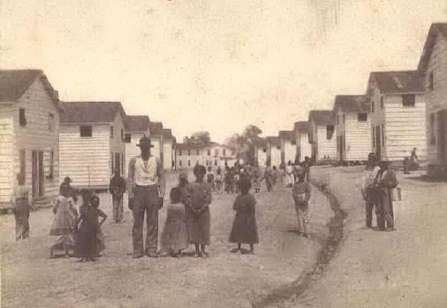

Our county seal is still the facade of Arlington House, an icon of white supremacy. But it’s changing – a second round of community submissions ended just yesterday. And in the history of the grounds of Arlington House we can find a better symbol for our county. We can remember what Arlington was in the decades between Lee and Lyon. We can remember Arlington as a beacon of opportunity for those who face racism elsewhere, of opportunity to have one’s own home and family in a community that we are building with our neighbors, the Arlington of Freedman’s Village that was a refuge from slavery and hate. We can remember the people who lived in the “white-washed, one-and-a-half story duplexes” of that village.

Tomorrow is Juneteenth. There will be celebrations and speeches, rightfully so. But don’t confuse symbolic celebration with real change. Choosing the Freedman’s Village duplex as our new county seal would honor Arlington’s Black history. It would honor the goodness in the soul of our county. But Juneteenth parades or a new seal are nothing but hollow symbols without antiracist policy reform. Legalizing apartments – real apartments, six units at least, with no setbacks or parking or special permits, on any lot – is one thing we can do to make these symbols real.

Arlington’s Black history isn’t just in our textbooks. Arlington’s Black history is being made every day. And Arlington’s future – for all races, backgrounds, and economic classes, for the children I and my generation may raise here – is for us to decide. Will we build homes for them?

Thank you for reading. To continue the conversation, my ARLnow editor has suggested publishing answers to your questions as a follow-up post in a Q&A format. If you have any questions about this or the rest of the series, please email me at [email protected] with the subject line Lyons Legacy Question.