Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

Lyon’s Legacy was a series that ran for the last four months on ARLnow, telling a story of the history of housing and racism in Arlington, and putting forward a suggestion for one way we could end the regime of economic exclusion that has dominated most of our county for the last century. As the series ran, some eagle-eyed readers kindly identified a few mistakes in the historical research.

In this follow-up article, I’ll address and hopefully correct those errors. You can read the whole essay, with these corrections incorporated, here.

All of these errors are significant, in the sense that any factual error in a piece of historical writing is significant. But correcting these errors does not change Arlington’s history of racial exclusion through single-family zoning and does not change our responsibility to end this exclusion by legalizing multifamily housing county-wide.

I offer my apologies to readers for my failures in research and my gratitude for those who helpfully corrected my mistakes.

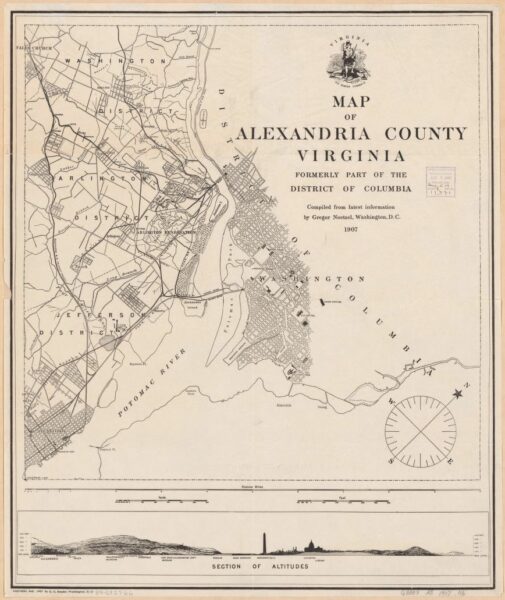

1. My description of Freedman’s Village failed to mention that residents were subject to labor requirements — a major omission. Nonetheless the Village was a better place for Black people to live in the 1870s than most of the rest of the South, as proven by their commitment to staying there until they were evicted in the winter of 1887. An imperfect attempt at racial inclusion would still make a fine symbol for our county.

2. Crandal Mackey’s raid on Rosslyn was not solely motivated by white supremacy. I failed to mention that one of the primary victims of the raid, Eddie Heath, was white; I underemphasized the extent to which violent and non-violent crimes did indeed take place in Rosslyn; and for the sake of the narrative I didn’t mention the same-day raid in Jackson City (another relatively unsegregated community).

Mackey was also a prohibitionist, and it may well be that he saw alcohol, rather than Black people, as the more significant barrier to Arlington’s development. But prohibition and racism were closely intertwined, and it’s worth remembering that drugs are still used as an excuse for selective enforcement and police brutality today.

3. Arlington did not institute segregation districts in 1912. Virginia passed a law in 1912 permitting localities to institute such districts, and five years later the law was deemed unconstitutional. During that five years, Arlington did not take advantage of its power to segregate. This detail is pretty much irrelevant to the history of segregation after 1917.

4. When touching on the history of economic racism in America, I referenced median household wealth. This can be a misleading indicator because it doesn’t account for variation in age, family size, etc. But my argument wasn’t meant to be nuanced — I was only trying to show that there exists a large historical racial wealth gap in our country. This inequity is real, and it can be illustrated by any number of more nuanced indicators.

No matter how it’s measured, the racial wealth gap has a major bearing on people’s ability to buy single-family homes in Arlington.

5. I failed to tell the stories of other racial and ethnic groups besides Black and white Arlingtonians. A major portion of our county today is Hispanic or Latino, and we boast sizable populations from countries all around the world. Those are fascinating, important stories, and they deserve to be told well in their own articles.

6. Frank Lyon’s developments were only slightly more car-oriented than others of that early period, and it is not clear that Frank Lyon, or anyone else in his day, saw car-oriented urban design as a tool of exclusion.

By focusing on the urban design of Lyon Village, I missed the forest for the trees: the real story here is of the indisputable car-dependence of Northern Virginia, and the rest of the nation, increasing over the 20th century. Lyon Village represents only the first emergence of that trend in our county, not its full manifestation.

My point is not that curved roads are racist. It’s that car-oriented design is racist in several ways, unsustainable, uneconomical, and harmful to public health. This includes Arlington’s current regime of free or subsidized parking, streets with several lanes for parked and moving cars but none for buses or bikes, and zoning that prohibits corner stores.

7. I didn’t mention that the company established by Frank Lyon, after Lyon left its leadership, went on to build apartments. It is an interesting quirk that these apartments are fair examples of missing middle housing, but they are not the work of Lyon himself, nor are they representative of the general trend in Arlington, so the Lyon Village Apartments don’t have much to do with the greater history here.

8. Without access to original documents, I found no clear evidence for whether or not Frank Lyon placed racially-restrictive covenants on every lot he developed. I only found that he used them in Moore’s Addition, one of his first projects. I admit that my initial source — in fact, the spark which set off this entire effort — was a secondhand story of a Lyon Village homeowner finding such a covenant in their deed. But even if Lyon did not use these covenants, they were common across the county. “Neighborhoods including, but not limited to, Alcova Heights, Bluemont, Glebewood Village, Monroe Courts and Westover had some variation of restrictive covenants that prohibited home sales to African Americans.”

Frank Lyon — and his individual legacy — is not really the problem here. The problem is the broader legacy of Lyon’s era of development in Arlington and the marks it left on our zoning code, marks which touch our entire county to this day.

I focused on Frank Lyon in this series not because he was the single villain, or even the most important figure, of Arlington’s early suburban development. I focused on Lyon in order to tell a story. And I hoped to push back on the published history of the man’s life, an essay from the 1970s by local historian Ruth Rose. This essay is thoroughly researched and well-written — I recommend it — but it is uncritical and only mentions race once, in a quotation. Rose’s work serves to vindicate Lyon’s vision for Arlington just as much as my series aims to question it.

9. Living in a single-family home does not make you a racist, and I never meant to say that it does. But denying your neighbor’s right to build and rent apartments on their own property is an action that can have racist effects.

10. I am not advocating government intervention to help middle- or lower-income people live in Arlington. Housing assistance and subsidies for affordable-housing developers are an established part of Arlington’s policy, but Lyon’s Legacy is not about the role of those programs.

I am advocating only for an end to the zoning code, dating from the days of KKK rallies and minstrel shows, which denies private landowners the right to build multifamily housing on private land in the vast majority of our county.

Thank you for reading. If you have any questions about this or the rest of the series, please email me at [email protected] with the subject line Lyons Legacy Question.

D. Taylor Reich is a native of Arlington and a graduate of H-B Woodlawn. They work as a researcher in urban mobility analytics with the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, where their research has been covered by international publications including The Guardian, BBC, and China Daily. Previously, they were a Fulbright scholar in Amman, Jordan. Taylor has served on the Arlington Transportation Commission and the Plan Lee Highway Community Forum.