Parent-Teacher Associations are how students get new spirit wear or go ice skating with their class. They host staff luncheons during Teacher Appreciation Week and help to pay for classroom supplies.

These independent organizations play a pivotal role in the kinds of enrichment opportunities to which students, primarily elementary schoolers, and teachers in Arlington Public Schools have access.

And a PTA’s ability — or lack thereof — to pay for these activities varies dramatically by zip code. Some PTA leaders tell ARLnow that they know the money their organizations raise can exacerbate existing inequities among Arlington’s schools, and are trying to raise awareness and effect change.

“We already have schools that are unequal and on top of that — like really thick icing on a cake — it’s making disparities bigger,” said Emily Vincent, a member of the Arlington County Council of PTAs.

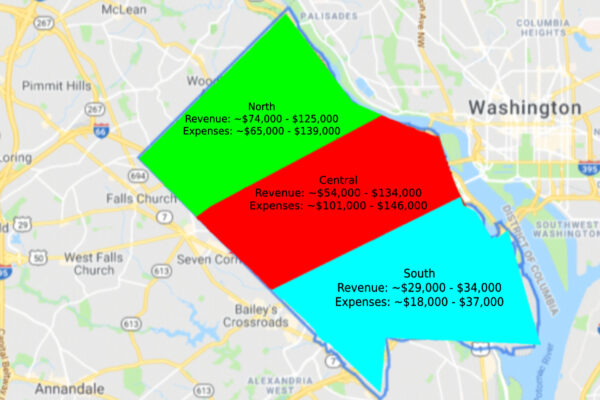

ARLnow requested and obtained copies of the 2018-19 budgets from a sampling of elementary school PTAs in northern, central and southern portions of Arlington. Individual PTA revenues ranged from $30,000 in South Arlington to more than $125,000 in North Arlington. PTA expenditures ranged from $18,000 to $139,000, a nearly eight-fold differential

While t-shirts and luncheons form the bread-and-butter of PTA expenses, other common expenditures improve the school through new furniture and books, or add to the curriculum with outdoor education and field trips.

Many PTAs did not respond to our requests for comment or for a copy of the budget.

Vincent said she saw similar discrepancies in the 2017-18 school year budgets she collected. PTA revenue at individual schools ranged from $20,000 to $200,000, and as a whole, Arlington PTAs spent $2 million. About 75% of that spending happened north of Route 50, she said.

(Northern Arlington neighborhoods are generally more affluent than those south of Route 50, which have higher poverty rates and lower household income levels.)

The Arlington County Council of PTAs is trying to tackle these entrenched discrepancies among its chapters. For about six years, the council has operated a grant fund: PTAs donate to the program and those who need extra funding apply for a grant. A 2019 report on the fund said most recipient schools use the money to pay for books, furniture and field trips.

But the grant fund can only go so far, especially because the requests are outpacing donations, Vincent said. Establishing a new policy could help address systemic inequities, particularly around PTA purchases that — if they were borne by APS — would result in a fairer distribution of resources, she said.

“We’re hoping for a culture shift,” Vincent said. “I do think a lot more of our PTA leaders understand that their decisions are not limited to their school.”

No school is an island

Over the last decade, outgoing Tuckahoe Elementary School PTA president Allison Glatfelter said APS has transitioned from a federation of schools that operated quasi-independently to a united school system. That transition, she said, revealed the extent to which some PTA budgets support school operations.

It was common for schools to improve their grounds through PTA funding without going through APS, she said. Budgets indicate that some associations have laid down track, installed sun shades or repaved their courtyards. Tuckahoe’s PTA once paid for a pond that the parent organization continues to maintain, she said.

Nowadays, she said wealthier PTAs spend money “on things that are hard to see.”

The budgets ARLnow reviewed indicated large expenses such as teacher training or, in the case of Jamestown Elementary in the 2015-16 school year, a dedicated horticulturalist.

PTAs get funding from donations and membership dues, but the bulk comes from fundraisers: from “no frills” fundraisers to auctions to restaurant nights in which a local eatery donates a percentage of sales.

According to the budgets that ARLnow obtained, the wealthier PTAs in north and central Arlington set aside tens of thousands of dollars for educational opportunities and capital improvements. Not all of that money gets spent, meaning the same schools have reserves exceeding $100,000.

Tuckahoe, for its part, is trying to change its relationship to fundraising and maintaining reserves, Glatfelter said.

“We definitely pared down fundraising. We don’t need the extra things that we were spending money on. Our kids don’t need extra field trips to places to which we can take them on weekends,” she said. “None of our schools should have giant budgets because we are an excellent school system with a lot of money.”

Vincent said she is not sure APS understands how much PTAs can contribute to school budgets. A policy that caps fundraising or redistributes donated furniture could equalize student experiences and ensure administrators keep tabs on school budgets that rely heavily on their PTA, she said.

The need for a policy

APS does not keep track of parent-teacher association contributions and typically does not rely on their funds for capital projects, said APS spokesman Frank Bellavia. That said, there is interest in drafting a policy that promotes equity between schools.

“As happens in many school divisions across the country, some PTAs can raise more money than others which does tend to lead to some inequities in resource availability,” Bellavia said. “This is why there is a desire to create a policy around this.”

But, he said, such a policy would have to consider how the school system could regulate independent organizations, which comes with a lot of open questions: Would it impose fundraising limits? What happens if a PTA raises more than the limit allows? How would APS provide equitable funding to schools who cannot fundraise to the same extent?

School Board candidate Mary Kadera said there needs to be more cooperation between schools and APS administrators.

“In a well-intentioned effort to provide support and enriching experiences for their own school communities, local PTAs sometimes end up exacerbating inequities across schools,” she said. “It’s really important for school and district leaders to work with local PTAs to ensure this doesn’t happen, and in particular to avoid setting any expectation that PTAs should be paying for the kinds of core instructional experiences, materials and support we want for every child in our school district.”

Changing the charity narrative

Located near the Lubber Run Community Center in the Buckingham neighborhood, Barrett Elementary School draws from both resource-rich and resource-poor neighborhoods, PTA president Will Le says.

“We’re a point of reference because we’re central,” he said. “We have a lot of need, but we have a lot of generosity.”

About 50% of Barrett’s students are English-language learners and 61% qualify for free- or reduced-price lunch. Some families have not been able to afford cleaning supplies, diapers and food during the pandemic, while others have had resources to spare.

Le said Barrett parents raised $26,000 in grocery gift cards, while the PTA used its own funds, a national PTA grant and purchases through an Amazon wishlist to distribute about $70,000 in essential items and products. Barrett also received donations from Yorktown High School teachers and Tuckahoe, he said.

The contributions are invaluable, but they cannot be the blueprint for how resource-rich and poor schools interact, Le said.

“I see that within our own PTA: Certain neighborhoods are more well-off, and we have the Buckingham community that is not well off, but they’re a part of our community. They do family dance night, they volunteer to cook and decorate hallways. Everyone’s pitching in, so it’s not like money and effort is going one way,” he said.

Le said he wants PTAs and schools to do more inter-school activities so the relationship is not defined by charity.

“I’m not one to make anyone feel guilty,” he said. “I’m somewhere between an idealist and realist: We know what the issues are but are there ways to lessen the disparity?”

Hannah Foley contributed to this report