Modern Mobility is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

Modern Mobility is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

The 20′ Clear Width rule of the VA Fire Code has removed on-street parking that had existed safely for decades, prevented the installation of protected bike lanes and made new sidewalk installations politically infeasible — and you’ve probably never heard of it. This rule can save lives by speeding fire response or cost lives by preventing safer street designs. Is Arlington finding the right balance?

What is the 20′ Clear Width Rule?

The 20′ Clear Width rule is codified in section 503.2.1 of the VA Statewide Fire Prevention Code: “Fire apparatus access roads shall have an unobstructed width of not less than 20 feet.”

A fire apparatus access road is, essentially, every road, street and driveway that a fire truck might need to drive on to get from the fire station to a structure that is on fire.

What makes an area obstructed? The Arlington Fire Department says that this area “does not have to be completely flat,” but past projects seem to indicate that curbs or medians within this area are not allowed.

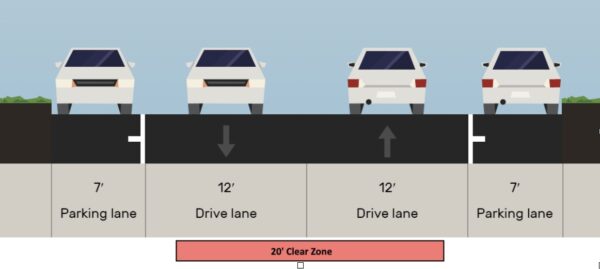

Here is an example Arlington residential street that more than meets the 20′ clear width rule because of its two adjacent, wide travel lanes:

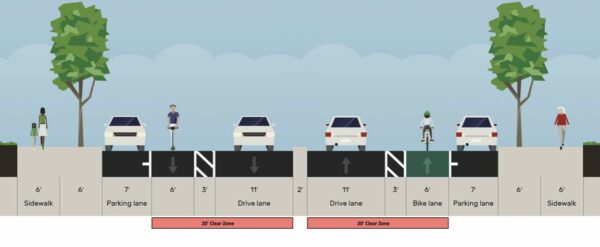

And here is an example arterial street with buffered bike lanes that meets the 20′ clear width rule because of the combination of the travel lane, buffer and bike lane, despite the car lanes being separated by a raised median:

What is it supposed to accomplish?

The Arlington Fire Department helpfully explains that the 20′ clear width rule is designed to make sure there is “continuous and unobstructed access to buildings and facilities” and to provide a “safe operational area around the fire apparatus to access compartments and equipment.”

The clear width isn’t so much to speed the truck’s arrival at the scene, fire trucks generally fit fine in normal lanes and factors like good grid connectivity are much more influential on response time than street widths. The clear width is to ensure that when the truck gets to the fire, there is space to park, extend outriggers (if necessary) and safely and easily access the equipment stored in and around the truck needed to fight the fire.

To the extent to which having 20′ of clear space at the scene of a fire speeds up response time by helping them quickly get set up and working, this portion of the fire code should help save lives in an emergency where every second counts.

Trade-offs & Consequences

On the other hand, the 20′ Clear Width rule has prevented numerous street safety improvements over the years, as well as causing the removal of on-street parking. These issues fall into two broad categories: yield streets and streets with medians

Yield Streets

A yield street is a quiet residential street where the driving area is narrow enough that one driver must pull to the side and yield to allow an oncoming driver to continue. Yield Streets calm traffic, reduce speeds and, thanks to the slower speeds, reduce traffic fatalities and serious injuries.

Drivers hate driving on yield streets as they feel unsafe, but that feeling causes them to drive more slowly which ends up resulting in a street that is pleasant and safe to live on and actually more safe to drive on.

Arlington’s Master Transportation Plan allows and endorses the use of yield street widths for quiet residential streets, allowing a “travel way” as narrow as 14′ in some cases. Yield streets have existed in cities throughout the world for many decades with no demonstrable increase in fire-related damage or deaths. Nonetheless, these yield streets don’t have 20′ of clear width and so do not meet the Fire Code without being granted an explicit exemption from the fire marshal.

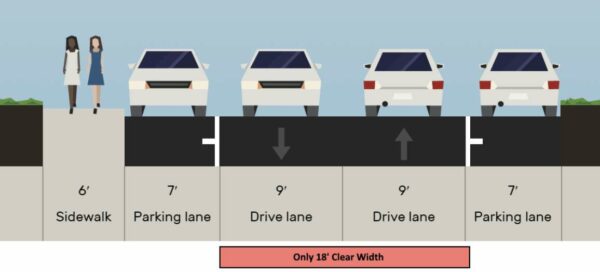

Here is our residential street from above, except with the addition of a newly built sidewalk. It now would function as a yield street (unless on-street parking is removed) and no longer meets fire code:

After having several sidewalk projects stopped by this 20′ clear width rule (or told they would have to remove huge amounts of on-street parking), Arlington’s Neighborhood Complete Streets Commission recently sent a letter to the County Board and County Manager asking for clarity on how the Clear Width Rule will be applied and guidance from the County on how they should move forward given the Clear Width constraints.

Streets with Medians

Many of Arlington’s arterial streets have medians and they have various jobs. Some of them are wide enough to provide a refuge for pedestrians crossing the street, for those unable to make it all the way across in a single attempt. Others are there to prevent left turns onto or off of a major street, or they contain trees for shade, landscaping for beautification or a place for treating the stormwater that runs off from the adjacent street.

The presence of raised medians is known to decrease crashes on a street, they have a calculated “Crash Modification Factor” in the highway safety manual. These medians, however, aren’t generally considered to be part of the street’s “clear width” for fire code purposes.

This effectively prevents medians from being added to two lane streets (one lane in each direction) as well as preventing existing four lane streets that have a median from being put on a “road diet” without also removing the median.

It also often prevents the creation of protected bike lanes on streets with a median since the “protection” for the bike lane — whether parked cars, planters or curbs — is generally considered an obstruction that cannot exist in the clear width area.

In Arlington, this clear width issue was the stated reason for why the Wilson Blvd Road Diet west of Larrimore Street resulted in a buffered bike lane rather than a parking-protected bike lane and a similar result on Potomac Avenue.

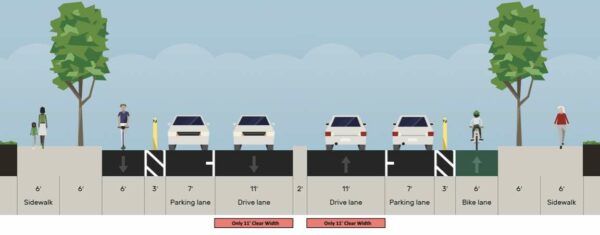

Here’s our arterial street from above, but with the bike lane and parking lane flipped to create a protected bike lane. Because of the median and the presence of the parked cars, this street no longer meets the fire code:

Medians make streets safer. Protected bike lanes make streets safer. But, in many cases, this fire code rule is preventing their implementation.

Clear Width Violations are Everywhere

Despite this regulation, it’s not hard to spot clear width violations across Arlington. Yield Streets can be found throughout Arlington (Upton Street is a good example) and streets like 6th Street in Penrose have a median even though their car lane and bike lane don’t add up to 20 feet.

When asked about this, the Arlington Fire Department acknowledges that “there are many streets that do not meet fire code” but claims that because the fire code is “not retroactive,” it “cannot be applied to an existing condition.” Given the County’s complete operational control over its own streets, and the clear width rule’s presence in the fire code since 1976, this claim seems utterly bizarre.

If the 20′ Clear Width is critically important to saving lives, why wouldn’t the County go back, slowly, over time, and apply it to its existing streets, especially when said application is usually as simple as putting up “no parking” signs?

The Structural Effect

This practice of only applying the rule to new streets has an unfortunate structural effect. Arlington’s single-family home neighborhoods are largely built out on existing streets. Major street modifications and new streets are being built almost exclusively as part of multi-family residential development.

This means slowly, over time, living on a quiet, safe, residential yield street could become a privilege reserved exclusively for those who can afford to buy a single-family home. Those who rent, or who can only purchase a duplex or condo, will only be able to do so on newer streets subject to the 20′ clear width rule and do not benefit from the safety and traffic calming effect of a narrower street width.

Experience Elsewhere

Oregon and Washington State both allow local communities flexibility to design street standards that go below the 20′ clear width. Many of those jurisdictions allow yield street conditions, but require 20′ clear widths in particular areas on each street (around the fire hydrant, for instance). The city of Baltimore, after a major dust up over the clear width being applied to protected bike lane projects but not other street projects, removed that requirement from their fire code.

Some jurisdictions (such as San Francisco) have started purchasing smaller, more nimble fire apparatus – sizing their equipment to the street they have & want, rather than forcing street design to conform to an arbitrary fire vehicle. DC recently had a demonstration of a smaller, all-electric fire truck.

Striking a Balance in Arlington

The Fire Code recognizes that some flexibility may be necessary to properly balance safety. In the 2015 version of the Fire Code (the most recent adopted version), language was added to grant local fire officials the authority to “permit modifications to the required access widths . . . where necessary to meet the public safety objectives of the jurisdiction” and the Arlington Fire Department has indicated that they work with Arlington’s traffic engineers to “balance the intent of the Code” and “achieve the goals of the project” on a “case-by-case basis.”

Despite these assurances, we see important transportation safety projects being stymied by the requirement. Perhaps we are not striking the right balance here between fire safety and street safety. It’s hard to know for sure. There are no published guiding principles, policies or criteria around granting exemptions to the width requirement. The exemptions that are granted are not recorded anywhere, so there is nothing to audit or examine to see which projects are making the cut and which are not.

Arlington can’t just nix the requirement, even if it wanted to. The fire code is adopted at the State level in Virginia, and localities are empowered to make the fire code stricter, but not less strict. The county can, and should, however, take the time to set out some criteria and policies around granting exceptions. Yield conditions could be allowed on residential streets, medians could be allowed within the clear zone if they don’t contain tall obstructions like trees, or if they have frequent breaks, in order to meet Arlington’s goals for Vision Zero.

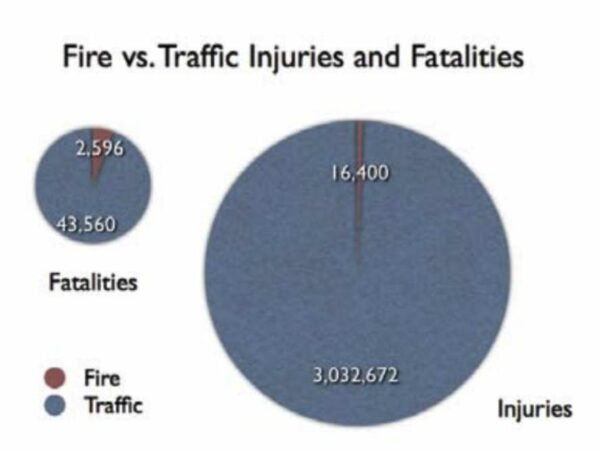

With street fatalities and injuries far eclipsing fire fatalities and injuries, it is important that we look at how we are balancing these conflicting safety needs in Arlington, or we may be saving one person from a fire, at the expense of 10 people in additional car crashes.

Chris Slatt is the current Chair of the Arlington County Transportation Commission, founder of Sustainable Mobility for Arlington County and a former civic association president. He is a software developer, co-owner of Perfect Pointe Dance Studio, and a father of two.