Modern Mobility is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

Modern Mobility is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

I have heard some variation on that sentence more times than I can count at public engagement sessions, County Board hearings and civic association meetings: “Cars just come speeding around that corner.” They shouldn’t be able to.

A street designed for pedestrian safety uses a solid, dependable and simple technique to force cars to slow down, the “corner radius.” Arlington is building streets using corner radii that are much larger than our policies say they should and they don’t seem to be taking into account a key concept: “effective” versus “actual” curb radii. The end result: drivers can whip around a corner at a high rate of speed making them much more likely to kill or severely injure a pedestrian in the crosswalk.

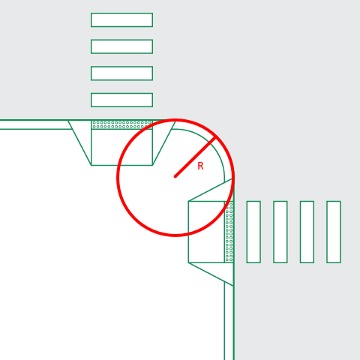

If you look at any street corner in Arlington, that corner is rounded off, it doesn’t actually come to a 90-degree angle. If, in your mind’s eye, you inscribe a circle onto that corner whose outline follows the contour of the curb line, the radius of that circle is the “corner radius.”

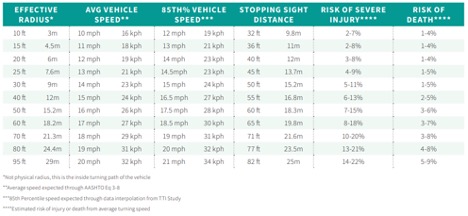

The smaller that radius, the sharper the turn a car needs to make and the slower they need to go to accomplish it.

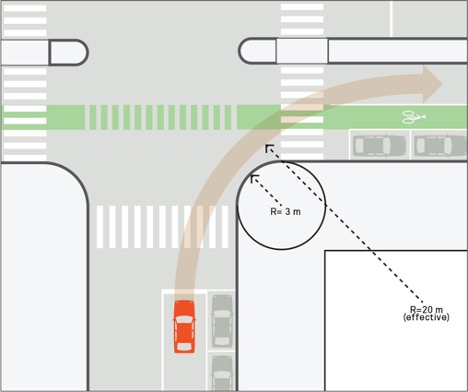

On many streets, turning cars don’t follow the curb line because the area they are supposed to be driving on is offset from the edge of the street by parking lanes, bike lanes, etc. This means that their “effective” corner radius is much higher than the “actual” corner radius.

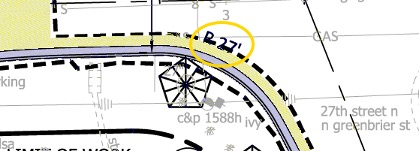

In this example, because the car is starting to the left of a parking lane and turning onto a street that has both a bike lane and a parking lane next to the curb, they can make a much more gently sweeping turn than the actual radius of the curb would indicate, and as a result they can make that turn at a much higher rate of speed.

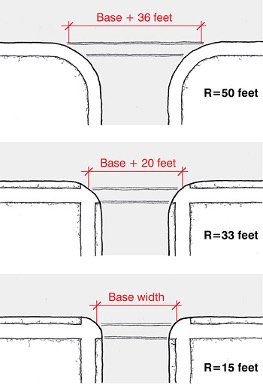

In addition to determining the speeds that cars travel through the crosswalk while turning, corner radii impact the distance that pedestrian have to walk in order to cross the street in the first place. The longer a pedestrian has to spend in the crosswalk, the longer their exposure to danger.

So how small should our corner radii be for safe pedestrian travel? The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) says “Minimizing the size of a corner radius is critical to creating compact intersections with safe turning speeds… In urban settings, smaller corner radii are preferred and actual corner radii exceeding 15 feet should be the exception.” The Federal Highway Administrator’s Pedestrian Safety Guide concurs: “The smallest practical actual curb radii should be chosen based on how the effective curb radius accommodates the design vehicle. An actual curb radius of 5 to 10 feet should be used wherever possible.”

The Pedestrian section of Arlington’s Master Transportation Plan is decent, but lags behind even the Federal Highway Administration in prioritizing pedestrian safety. It says that “the standard curb return radius is 15 feet with larger radii used when necessary to accommodate the low‐speed turning movement of expected truck and bus traffic.”

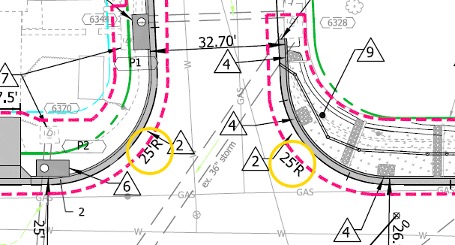

In practice, however, Arlington’s Department of Transportation completely ignores these policies and guidelines. A quick spot-check of recent construction plans produced by Arlington County shows typical corner radii of 25′ or more. This Neighborhood Conservation project in a quiet residential neighborhood in North Arlington with little to no bus or truck traffic nonetheless specifies corner radii of 25′.

This project that reconstructed 23rd Street S. and S. Queen Street? Also a 25′ radius. This project at 2nd Street S. and S. Kensington Street features a 20′ curb radius. This N. Evergreen Street project features a 27′ curb radius for one intersection and a 25′ radius for another. This N. Greenbrier Street project features a delightful assortment ranging from as high as 30′ down to one corner with a 12′ radius; 25′ is the most common here as well.

To make matters worse, in most of these situations, there are parking lanes along one or both of the streets that form these corners. As a result, the “effective” curb radius is even larger — often three to four times larger. A 25′ physical curb radius that results in a 100′ effective curb radius because of parking lanes on both streets results in a massive difference in speed that drivers can take through the turn, a huge increase in how long it takes them to stop and a major increase in how likely they are to kill or seriously injure a pedestrian. To make matters worse, these high curb radii mean the crosswalks at these intersections are longer than necessary putting pedestrians at risk of these higher speed cars for longer periods of time.

[source]

As part of its Vision Zero initiative, Arlington has committed to updating its design guidelines and producing a “toolkit” of safety designs. It is critically important that we take a hard look at how we design our street corners and take into account the “effective” corner radius. Our stated policies are lagging behind peer cities and modern guidance in prioritizing pedestrian safety and our actual on-the-ground designs don’t even live up to our stated policies. Cars should not be able to “just come speeding around that corner.”

Chris Slatt is the current Chair of the Arlington County Transportation Commission, founder of Sustainable Mobility for Arlington County and a former civic association president. He is a software developer, co-owner of Perfect Pointe Dance Studio, and a father of two.