(Updated at 4:10 p.m.) A public art plan slated for consideration this weekend has angered some Green Valley residents, who say it essentially erases a portion of the historically Black community.

After multiple years of community engagement and study, county arts staff have drafted an update to the Arlington’s Public Art Master Plan (PAMP) — first adopted in 2004 — to reflect changing county values, such as equity and sustainability, and more modern public art practices. The updated strategy for bringing art into public spaces is slated for a County Board vote this Saturday.

“Public art will continue to be a timely and timeless resource, responding to current community priorities while creating a legacy of artworks and places that are socially inclusive and aesthetically diverse features of Arlington’s public realm,” the county wrote in a report about the updated plan.

But members of the Green Valley Civic Association are urging County Board members not to approve the updated plan without wording changes to the various references to their community.

“This master plan aims to nullify a historically Black community in Arlington,” they said in a letter to the County Board dated Nov. 1. “It is a painful and blatant attempt to suppress the Green Valley community and rewrite our historical narrative.”

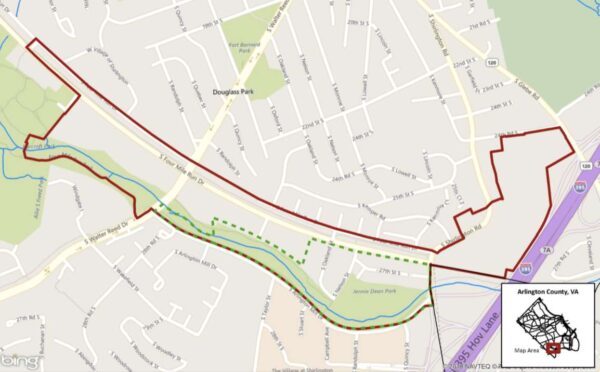

Settled by free African-Americans in 1844, Green Valley — formerly known as Nauck — is one of Arlington’s oldest Black communities. Its borders are S. Arlington Mill Drive to the south, the Douglas Park neighborhood (and S. Walter Reed Drive) to the west, I-395 and Army-Navy Country Club to the east, and the Columbia Heights neighborhood to the north.

Geography and names comprise two chief concerns for residents, who take issue with the document’s use of the monicker “Four Mile Run Valley” to refer to an area north of Four Mile Run near Shirlington — much of which is actually part of the historic Black community.

The name “Four Mile Run Valley” started being used widely by the county in connection with a planning study that discussed the proposed creation of an “arts and industry district” in the area. But Green Valley residents are taking exception to the term being used instead of their neighborhood’s actual name.

“This is wholly incorrect and offensive,” the civic association said.

More from the letter:

The report defines a fictitious community of “Four Mile Run Valley.” This heretofore non-existent community is defined as running from the “north bank of the stream where the lower and upper reaches meet.”

It further, incorrectly states, that Shirlington Village is “on the south bank of Four Mile Run.” It is not. The northern border of Shirlington Village begins in the middle of Arlington Mill Drive.

The report states, “Green Valley is a historically African-American neighborhood to the north of Four Mile Run Valley.” This is wholly incorrect and offensive. Again, “Four Mile Run Valley” is a fictitious name created by county staff. It is not a location. The southern border to Green Valley begins in the middle of Arlington Mill Drive. To try to push the historic boundary of our community up the hill is unconscionable and disrespectful of what Green Valley means to Arlington.

Civic association president Portia Clark says this turn of phrase is part of a pattern of erasure.

“This isn’t the first time the county has tried to paper over Green Valley. Green Valley established in 1844 was rebranded Nauck in 1874, after a confederate soldier purchased land in our freed Black community,” Clark said. “We finally got our name back in 2019, only to find the county trying to discard us again. This time the county tried to hide the deed in the middle of a 200-page arts report.”

Just after publication of this article, county staff told ARLnow that some of the changes suggested by the civic association have been made.

“Staff did receive the letter and incorporated several revisions into the plan per the community’s suggestions, as we have endeavored to do with all public comment we have received to date,” said Jim Byers, Jr. of Arlington Cultural Affairs. “These changes will be reflected in a matrix incorporated into the Board report which will be available tomorrow.”

In addition to concern about the community name, the letter writers say the arts document doesn’t include work that community members had done regarding their vision for the area.

“In 2018, the County Board adopted a plan that would move forward on opportunities for an arts and industry district in Green Valley. A well-researched blueprint for this district was prepared by County Board-appointed committee members and enthusiastically endorsed by the community,” said Robin Stombler, the civic association’s first vice president. “Why would a public arts master plan not even reference this rich resource?”

She added that the plan’s vision for arts in Green Valley should include more than permanent installations, and should integrate the community’s industrious side.

“From furniture-making to metal-working, from technological innovation to maker-spaces, from recording studios to culinary arts, in Green Valley we view the arts broadly,” Stombler said. “This report should too.”

They requested the county tone down a section touting collaborations with the community to tell underrepresented and forgotten stories through public art.

“We have witnessed inaccurate portrayals of history of Green Valley, including in the drafting of language for the FREED sculpture to be placed in John Robinson, Jr. Town Square,” the letter said. “While we have been reviewing and commenting on the county’s language, and hope to resolve the misinformation, it is disturbing to have to continually make these corrections.”