This story was made possible by the ARLnow Press Club. Join today to get the exclusive Early Morning Notes email and to help support more local reporting.

You’ve probably seen, spoken to, been directed by, or maybe even gotten a ticket from Arlington County police officer Adam Stone.

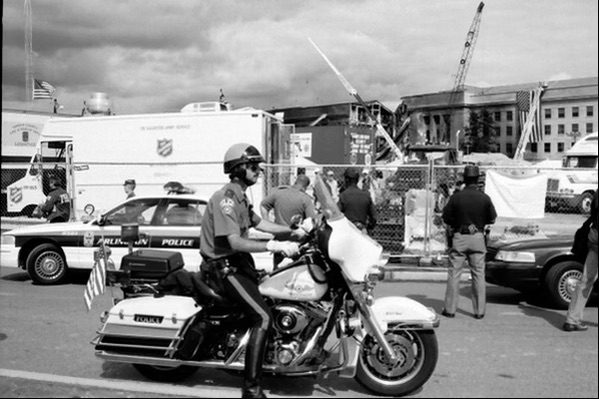

Ubiquitous on Arlington’s streets riding his gleaming blue and white motorcycle, Stone is a well-known presence in the community for his work patrolling, manning road closures, following motorcades, or letting kids try out his ride. He’s spoken up for police officers’ mental health while talking about his own challenges. Stone has escorted presidents, protected citizens’ right to protest, and worked dozens of Marine Corps Marathons and July 4ths.

And, after more than 30 years on the force, Stone is retiring.

As an appreciation of his upcoming retirement, Officer Adam Stone laid a wreath at the @ArlingtonNatl Tomb of The Unknown Soldier. Throughout his 33 years of dedicated service, Officer Stone has supported veterans and military members visiting and living in Arlington. pic.twitter.com/lQ6h3v5pzJ

— ArlingtonCountyPD (@ArlingtonVaPD) March 9, 2022

“Through all the years that I’ve been here, whether it’s good police times, bad police times, everyone in Arlington has always been super, super supportive,” he tells ARLnow, standing in front of his beloved motorcycle, yards away from the Iwo Jima memorial. “Not so much when I’m giving people tickets.”

Stone grew up in Long Island and joined the Arlington County Police Department in 1990, becoming part of the motorcycle unit four years later. And he’s been in the unit ever since, living in the Pentagon City area for the majority of his career.

“I always wanted to do two things in life: be a fighter pilot or be a cop,” he says. “Once I realized how much math was involved in flying, it was definitely police work for me.”

He holds countless memories of years of service. Some are still hard to think about, like the smell of concrete and kerosene after an airplane struck the Pentagon on 9/11. Others make Stone smile, even to this day. He’s met and taken pictures with six U.S. presidents, “still mind-blowing,” he says, and because his job often takes him to heavily guarded areas, he’s had the privilege of visiting places few others have.

“I’ve gotten to use the most secure bathrooms in all of the D.C. area,” he says.

And how are they different from other bathrooms?

“You have to walk through two doors to get there, ” Stone laughs. “And they are clean.”

Being a motorcycle cop also has added risks. He’s been hit three times, but says he’s gotten away with no serious injuries. He admits that he’s actually never told his mom that he rides a motorcycle every day at work. And when he retires in April, Stone says he will be “hanging up the helmet” and will never ride a motorcycle again.

Since he joined the force, Stone has seen noticeable changes in policing.

For one, the attacks of 9/11 added more training to a police officer’s job. Additionally, the concept of community policing, which wasn’t as highly valued back in the 1990s, has become an essential part of the job. For him, though, it comes naturally.

“For me, [community policing] means just being a good cop and it means the simple things like waving back when people wave at you and giving a smile. If you see some kid pointing at you [when driving by], make a U-turn, and take a few seconds to talk to them,” Stone says. “It’s the basics of being a good guy and being a good public servant.”

Paying attention to officers’ mental health was also not as appreciated back then. In recent years, Stone has been at the forefront locally of advocating for police officers’ well-being and making sure they know it’s okay to ask for help. More police officers die by suicide than heart attacks, accidents, or shootings, according to a recent study.

This stems from his personal experience, struggling with mental health challenges while serving.

“It happens to the most macho of us regular officers and that there is help,” Stone says. “Please take advantage of that.”

Stone has worked with department leadership to develop what he calls an “excellent” officer wellness program that provides individuals the resources, the time, and tools to meet the mental health challenges that many officers face. He calls his work with other officers and helping to develop these programs his “greatest accomplishment” in his 32 years of policing.

After those more than three decades, Stone has a few words of wisdom for young recruits looking to join the police force.

“If you are doing the right thing, the department will always back you up. More importantly, the [community] is going to back you up,” he says. “And if you have support from the community because you are doing good police work, it’s the best feeling in the world.”

Of course, he’s going to miss ACPD, motoring around the community, and chatting it up with Arlingtonians — “I’m a pretty talkative guy,” he says.

It’s the greatest job in the world, Stone says, but it’s his time to go. He’s done everything he’s hoped to do as an Arlington County police officer and lived a dream he’s had since a kid.

“I grew up reading comic books and always wanted to be a superhero,” Stone says, breaking into a smile. “This is the closest thing you can be without having to wear tights in the middle of Rosslyn. Which would get some attention.”