Over the last four days, fights involving kids and weapons broke out near Gunston and Thomas Jefferson middle schools, while Wakefield High School had multiple trash cans set on fire.

Those are the most recent incidents in what some parents — mostly to middle schoolers — say is a rash of fights, threats of violence and other concerning behaviors happening in the public school system.

Earlier this month, for example, a mother told the School Board her daughter at Gunston Middle School was attacked by other students.

“My daughter’s eye is messed up,” Shana Robertson told the Arlington School Board on March 10. “She was jumped by two boys and two girls, and nothing has been done.”

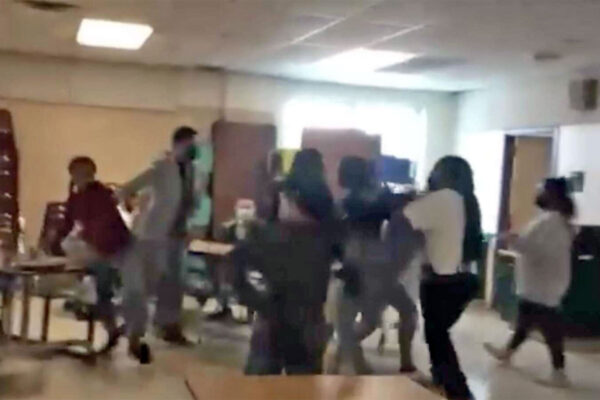

ARLnow spoke to multiple parents who say these issues are happening across the school system. We also reviewed several videos of brawls on school grounds, or near them, recorded by students this year.

Arlington Public Schools confirms to ARLnow that the school system has, in fact, noticed an increase in the number of reported fights and incidents this school year.

“This rise in concerning behaviors follows the national trend that is not unique to Arlington, as students re-acclimate to being back in school and face increased stress and anxiety, as well as other mental health and social-emotional challenges due to COVID and the trauma students experienced as a result,” APS spokesman Andrew Robinson said.

The trend has prompted some parents to call for more disciplinary actions for students and a renewed conversation about whether to reinstall Arlington County Police Department School Resource Officers, who were removed over the summer out of concern for racial disparities in juvenile arrests.

Opinions on reinstalling SROs are mixed. Some say this would help keep students in line and some say they may help — but they will not address the root cause. Others say SROs would not only fail to address the root cause, but they would also needlessly drive up the number of arrests.

“This is happening across the country, even at schools with police officers,” says Symone Walker, a member of the Arlington branch of the NAACP’s education committee and a former ARLnow columnist. “You really have to start addressing the emotional needs, the physical needs, the academic needs. Of course, there’s stuff going on at homes where families are stressed. Parents are angry and the kids are soaking it all up — it’s a much deeper problem.”

In the trenches

One Gunston Middle School father said his kids avoid going to the bathroom out of fear of running into a fight or kids doing drugs.

“Essentially, as far as I’m concerned, our children’s safety is the foundation on which their education is built,” the father said. “If they’re not safe in their schools, how can they feel comfortable trying to learn? If they’re too worried about not getting assaulted, having drugs everywhere, they can’t concentrate on what they’re there to do, which is learn.”

A mother to a Swanson Middle School student said kids are watching pornography and bullying each other during P.E. class and on school buses. She added that mental health is a “huge factor” that needs to be addressed before students hurt themselves more.

During the last School Board meeting, Robertson said that in addition to fighting each other, students are disrespectful to teachers, staff, school leaders, bus attendants and drivers.

“I was in Wakefield the other day and one student told a lady to ‘suck his you-know-what,'” she said. “Why are you guys allowing this to happen to the staff?”

This school year has also seen a lockdown at Yorktown High School in February and a lockdown at Washington-Liberty High School in October, each related to threats that turned out to be unfounded. In January, police and school staff investigated reports that a student reportedly brought a weapon to Gunston, and police eventually found an airsoft gun at the student’s home.

In December, a student wielded a knife against another student on the walk home from Swanson Middle School, and in October, a girl was touched inappropriately during the Yorktown homecoming football game, prompting a police investigation, walkouts and a petition against sexual misconduct at the school. In early August, a brawl broke out outside of the school amid summer classes.

“It’s a much bigger problem than I think APS is able to handle,” the Swanson parent said. “We have no recourse. They’re not providing any information on how they plan on addressing it.”

Robinson responded that APS has been “very open and transparent with our families, students and staff to notify them when these incidents occur, providing frequent reminders about the importance of reporting any concerns they see or hear.”

It starts young

Some mothers say this behavior starts as unchecked bullying in elementary school, and said APS needs to do more to intervene in these instances.

“It’s starting at an early age,” said one mother to a Williamsburg Middle School student. “I don’t think that high schoolers started behaving badly because SROs were taken out. It started in elementary and it worked its way up.”

Another mother said her child was bullied for many weeks, and despite multiple meetings with school leaders and talks with the parents of the alleged bully, the situation did not improve.

“I was told that ‘Arlington does not believe in consequences in fifth grade,’ despite their clearly defined anti-bullying policy,” she said.

Possible solutions

Whatever the cause, officials are mulling multi-faceted solutions.

So far, APS has tried to improve school security through investments in additional counselors, enhanced building safety and stronger emergency management operations. The School Board is poised to get an update on school security during its meeting tonight (Thursday).

But even if the school system were to entertain reinstating SROs — which the Alexandria City Council did in October after reports of out-of-control student behavior and multiple fights — the police department has said it would take up to two years to bring the program back. That is because the SROs have all been reassigned or retired and ACPD faces a staffing crunch.

Even without police in schools, they officers respond immediately whenever they are needed, Robinson says.

But as the conflicts and concerning behaviors increase, Arlington County officials are working with APS to explore recommendations and approaches to mitigate them.

This work is ultimately part of the Restorative Arlington Strategic Plan, which seeks to introduce practices into the county’s public schools, legal system and community settings that hold people accountable for their crimes without putting them through legal processes.

“This is an issue that requires all of us in the community — administrators, teachers, parents and students — to teach our children about appropriate conduct and behavior whether at school or participating in other community activities,” said Kimiko Lightly, the coordinator for Restorative Arlington.

Meanwhile, Robinson said APS remains focused on working with administrators and mental health teams to prioritize social-emotional learning and provide counseling, interventions and other supports to students experiencing challenges at school.

But the NAACP’s Walker says there is a disconnect. In her estimation, the restorative practices and social-emotional learning county and school officials talk about do not seem to be implemented effectively in the schools or embedded into concrete policies.

“We’re stuck and our kids have no tools, are suffering because of it,” she said.