Arlington County doesn’t always get public engagement right — but officials say the county is doing better than it did a few years ago.

The pandemic has served as an impetus for accelerating changes already in progress, including a move away from exclusively in-person engagement to more virtual and hybrid community outreach options.

Mark Schwartz said one of his top priorities when he was named County Manager in 2016 was to enhance engagement and communications. This was on the heels of the completion of the county’s community facilities study, which looked at public facilities given a growing population; Schwartz said the group had challenges engaging residents.

“And since then, we’ve learned a lot about communicating and public engagement, especially over the last two years with Covid,” Schwartz said during an update to the County Board last week.

“And I will be the first to admit, I’ve admitted it here, we don’t always get it right,” he continued. “But we’ve come a long way in weaving not just the old style corporate communications but true engagement into our efforts as we develop and implement policies.”

Engaging the community

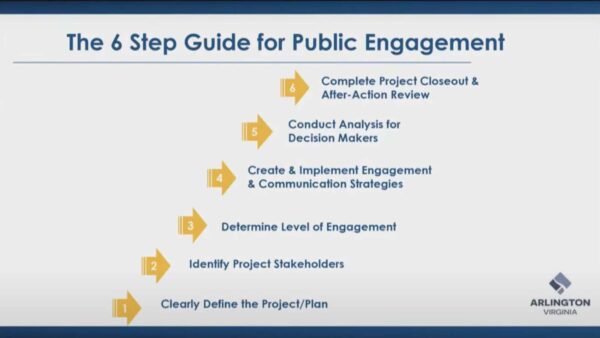

While the county developed a six-step guide to public engagement in 2018 for capital projects, it’s also applied to planning, policy-making and programs, said Bryna Helfer, an Assistant County Manager who oversees the Office of Communication and Public Engagement.

“One of the things that we still have to work on is getting those folks that are highly impacted but have really low awareness,” Helfer said. “We spend a lot of energy on people with high awareness and low impact and so really [we have to be] intentional.”

The level of public engagement intensifies with the size of a project, Helfer said. The higher the level of impact, positive or negative, the more engagement and outreach.

“We’re not showing up to do charrettes if we’re just painting the bench,” she said. “We’re really aligning the tools and strategies with the level of engagement and training all of us to use the right tools.”

The county has used roundtable discussions with civic associations and other organizations to inform them how to ease the groups’ pain points. After some of those conversations, the county created the Civic Association President Toolkit, which includes a county staffer sitting down with every new association’s president and reviewing a list of county resources.

The county also developed a multifamily complex directory to help engage those residents, which make up 60% of the county’s population, Director of Public Engagement Jerry Solomon said.

“That’s an example of a big win that helps us to that greater capacity building that we know our community needs,” she said.

Demographic dashboards give officials an idea on how to strategize and recognize gaps in participation, Solomon said. While planning engagement, they apply an equity lens, asking questions like: who benefits, who’s burdened and who’s missing?

Past criticism

Arlington’s community engagement ethos is commonly referred to as the “Arlington Way,” a vaguely defined term for the local ideal of an open conversation between county government and residents.

But the Arlington Way has taken some barbs over the years, as Arlington’s equity ideals clashed with the reality that effectively participating in the county’s decision-making processes often required hours of in-person engagement — nearly impossible for many shift workers, young parents and people struggling to make ends meet.

Last year the “Arlington Way” was a point of conversation at the Board after controversy over the start time of a north Arlington farmers market made the meeting run long, effectively shutting out participation from low-income residents there to speak about filthy conditions at the Serrano Apartments.

In 2020, community leaders from the Green Valley neighborhood criticized the county for not engaging the community before a temporary parking lot was built for WETA — relying instead on a legal ad published in the Washington Times as a primary form of public notice.

Earlier this year, a typo on a public hearing notice promoted the wrong date, adding to a continuing conversation by County Board members who have critiqued the engagement process.

And even online engagement has been critiqued for attracting a narrow set of interested parties rather than a broad swath of the public. Respondents to a recent survey about historic preservation, for instance, were overwhelmingly older, white homeowners.

Covid learning curve

Covid shifted public engagement to the virtual realm. The county started doing virtual walking tours for site visits and virtual public comment — and learned more about who participates in virtual meetings.

“Coming out of Covid, we think we will be able to do some in-person things, we’ll continue to use our virtual platforms — because the greatest thing has been people participating while watching their kid’s softball game — and that hybrid model where we come together with both,” Helfer said.

At the outset of the pandemic, Helfer said the county made assumptions that the lowest income residents and those that don’t speak English as their first language might not participate virtually. But that was not necessarily the case.

“But we learned something very different during the trust conversations that [the County Board] led and was just thrilled with over 60 participants,” she said, noting they offered five different languages, and three sessions in Spanish. “I mean it was really an eye-opener but we also had to use some different tools.”

During Covid, they reached out to community partners for help spreading information and distributed a lot of fliers, as well as more direct mailers like postcards, Director of Strategic Communications Jessica Baxter said.

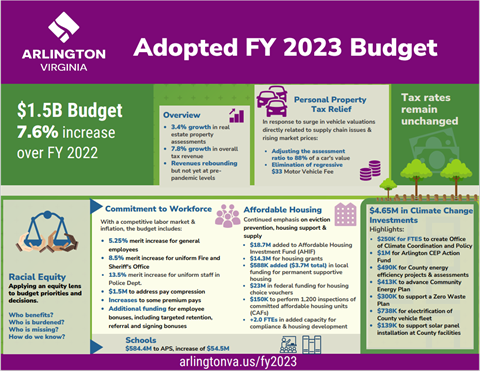

Over the last two years, the county has also increased the use of visuals to simplify complex information coming from the county, Baxter said. For the budget, they took a 900-page budget document and distilled that information into six infographics.

Other examples of new forms of public engagement and information distribution include an online county project map and Arlington’s new website, which had a number of problems after launch that have been addressed, though there’s still some tweaking and search engine optimization to be done.

“Digital tools work immensely well,” Baxter said.

But not everybody has internet access or mobile devices. Solomon said that the county also provides text message and voicemail options so residents who aren’t online can still be a part of decision-making processes.

The ultimate goal: casting a wide net by engaging more Arlington residents on their own terms.