From Philadelphia to Los Angeles to nearby Fairfax County, and here in Arlington, prosecutors running on criminal justice reform platforms were elected in a wave.

But since they’ve taken office, some have questioned whether their approach to crime is too soft. A recall election in San Francisco ousted its chief prosecutor, and last year, Arlington’s Commonwealth’s Attorney Parisa Dehghani-Tafti also faced a recall campaign, though it never seriously threatened her tenure in office.

Since she took office in January 2020, some types of crime have increased. At the same time, the pandemic pushed her, defense attorneys and the sheriff’s office to reduce the number of people jailed, and staffing shortages led to a cut in some police department services, such as follow-up investigations on property crimes it deemed unsolvable.

Dehghani-Tafti tells ARLnow that when crime is up, the “tough-on-crime crowd” says to “be tougher” and when it’s down, they say to keep jailing people because “it’s working.” But she believes progressive policies and expanding diversion programs for nonviolent offenders can better help them stay on the right side of the law.

She emphasized that her office takes violent crime seriously. The violent crime rate in Arlington was below the state and national averages in 2021. Meanwhile, police officers working with Dehghani-Tafti generally approve of the way her office pursues violent crime charges, Arlington Police Beneficiary Association President Rich Conigliaro tells ARLnow.

Fewer prosecutions of nonviolent crimes

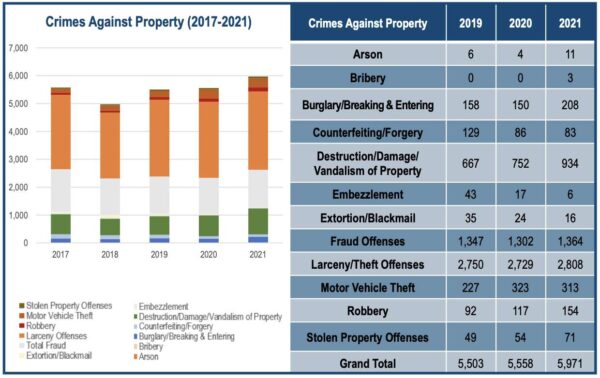

Although the police don’t believe Arlington has a major crime issue, the department has seen more crime sprees in the last few years, Conigliaro said. There was an overall 8.5% increase in property crime in 2021 compared to 2019, according to ACPD’s annual report.

Police have dealt with cases where the defendant had committed multiple property crimes, such as burglaries, in jurisdictions across Virginia. In one such case, a Maryland man, who was out on bail for charges in Fairfax County, was arrested in Arlington on similar charges, including stealing and spitting on an officer after his arrest.

After that incident, Dehghani-Tafti’s office dropped two charges and downgraded a felony charge into a misdemeanor as a plea agreement. His 180-day jail sentence in Arlington was suspended and he was extradited to Maryland to face prior charges there, according to court documents.

Dehghani-Tafti’s office has downgraded felony charges into misdemeanors for cases that “normally would not have seen that level of a plea bargain being agreed upon” on multiple occasions, Conigliaro said. Detectives are concerned with this trend, he added.

Brad Haywood, the chief public defender in the county, also said Dehghani-Tafti’s office seemed less likely to press felony charges where a misdemeanor charge may apply, such as with nonviolent or minor property and drug cases, he said.

Haywood said her office seems more willing to give people with behavioral issues a second chance by ensuring they receive treatments instead of jail time, unlike her predecessor Theo Stamos. Stamos, who is now working in the office of Attorney General Jason Miyares, declined to comment for this article.

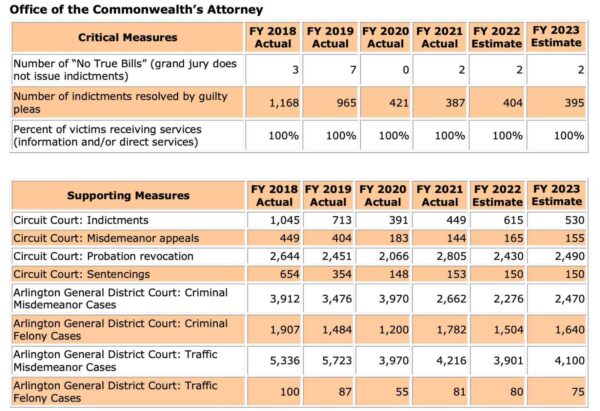

Generally, there have been fewer felony indictments under Dehghani-Tafti compared to Stamos, according to performance data gathered in the latest proposed budget from the Commonwealth’s Attorney office. The number of indictments issued by the Circuit Court decreased 37% from 713 in fiscal year 2019 to 449 in fiscal year 2021. The number of sentencing events dropped by almost 57% from 354 in fiscal year 2019 to 153 in fiscal year 2021.

The number of criminal misdemeanor cases that appeared before the General District Court also decreased by 23.4% from 3,476 in fiscal year 2019 to 2,662 in fiscal year 2021.

In Dehghani-Tafti’s view, prisons cannot effectively rehabilitate an offender. She cited a meta study published by the University of Chicago Press last year that showed incarcerations are less effective in reducing recidivism.

Dehghani-Tafti believes the biggest change she brought to Arlington was creating new diversion programs for adults. Her office is taking part in the Motion for Justice Project, which connects participants to social services and treatments, as well as partnering with the nonprofit Offender Aid and Restoration to provide diversion programs.

“I came in guided by the idea that safety and justice are not opposite values, they are rather complementary values,” Dehghani-Tafti said. “And that we can treat people like people and crime like crime.”

Impacts on recidivism

There is some concern among the police department rank-and-file about the way the Commonwealth’s Attorney’s Office handles certain nonviolent but repeat criminals. When Dehghani-Tafti’s office came across arrestees who had committed property crimes in other jurisdictions, Conigliaro claims “there has just been a propensity to let those people go.”

He also says detectives haven’t been consulted as much as the previous prosecutor on plea bargain decisions.

It became harder for the police to keep morale up after seeing the cases the officers “worked hundreds or even thousands of hours to solve, end up getting pled down to misdemeanors,” Conigliaro added.

Responding to concerns about a rise in the crime rate, especially property crime sprees, Dehghani-Tafti said it was not her policies that were to blame, but a lack of investment into diversion programs that would make Arlington safer.

“What we need to be doing if we really care about public safety is working on gun restrictions, working on hospital-based interventions, working on job training programs and working on education and housing, making sure that the hierarchy of needs is met,” she said.

In particular, when Dehghani-Tafti comes across repeat offenders of nonviolent crimes like trespassing or petty larceny, she believed that meant the criminal justice system had failed those people previously. She believes her office should “try to get to the root causes” of those repeat offenses instead.

“Primarily, when you see repeat offenders, what that tells you is that everything we’ve been doing so far, for the last 40 years, is not working,” she said.

She emphasized that understanding why a person became a repeat offender and whether that person was willing to put in the effort to engage in treatment programs would be factors in deciding whether to recommend that person to diversion programs instead.

2/2 I understand the easy answer is to simply say: keep people locked up for as long as possible because if they’re locked up they can’t commit any crime. But, what about if doing so increases the chance they will reoffend once released, thereby decreasing public safety?

— Parisa Dehghani-Tafti (@parisa4justice) July 13, 2022

Academic research shows that felony convictions may make it harder for those convicted to keep clean after they get out of prison, Sarah Fischer, professor of criminal justice at Marymount University in Arlington, told ARLnow.

Particularly if a person goes to jail at a young age and is released while still within that age range, when coupled with a lack of education and difficulty in finding a job after serving time, “the cycle can restart,” Fischer said.

Around 52% of people released from prisons after serving time for a property crime were arrested again for property crimes within five years, which was a higher percentage than those serving time for a violent felony, drug or public order offenses, according to a U.S. Department of Justice report in 2021 that tracked crime in 34 states.

Tension with judges

Judges’ attitude toward plea agreements under Dehghani-Tafti was another significant difference observed by Haywood as a public defender. He said that hundreds of felony cases during Stamos’s time as Commonwealth’s Attorney were resolved with plea agreements, without objection from the Circuit Court.

However, judges were more likely to hold plea agreements offered by Dehghani-Tafti and her office for further consideration instead of signing off on them. He believes the judges were becoming more skeptical, but not because the deals were getting more lenient.

“As Parisa took over, we didn’t get the exact figures on that, but ballpark, it’s probably a third of them are taken under advisement or rejected by the Circuit Court,” Haywood said.

As previously reported, Arlington judges even required her office to submit written briefs to explain why they were dropping or amending charges during her first week in office, which was not required previously.

She claimed judges have held her office to “a different standard than the prior administration.”

Nationwide, there is more apparent tension in courtrooms among judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys with different philosophies and ideologies, Fischer said.

The tension has existed for decades, but the friction is “becoming increasingly politicized,” Fischer said. In the past, judges and attorneys could put their ideological differences away when working, but now these philosophical differences are getting attached to political affiliations.

“I think we are often assigning political ideologies and conflating them with legal ideologies,” Fischer said.

“Sometimes the two are related,” she added.

This article, which took about a month to report, was supported by the ARLnow Press Club. Join today to provide a boost to local journalism in Arlington.