(Updated at 4:30 p.m.) Arlington County is gearing up to make a decision on whether to rezone areas that only allow single-family detached homes.

And the debate has gotten fierce.

Proponents say the changes will give renters, middle-income residents and many people of color a fighting chance to buy in Arlington. Opponents say the plan will forever change local neighborhoods, won’t serve lower-income residents, will displace seniors and and people of color, and will cut the county’s tree canopy.

Two cities — Portland, Oregon (pop. 641,162) and Minneapolis, Minnesota (pop. 425,336) — have walked this path before, enacting similar policies in 2020 and 2018, respectively.

Both policies were described as controversial, as local officials considered whether to adopt them. In Portland, concerns over displacement of low-income renters led some officials to vote against the changes. In Minneapolis, support for the change among local officials was near-unanimous despite some vocal opposition, deemed NIMBYism in a 2019 article in The Atlantic.

Since then, both municipalities have clocked a modest number of “middle housing” units. A similar story could play out in Arlington, where the county estimates about 19-21 units could be built per year, but support for and opposition to “Missing Middle” continues to intensify.

“Our goal wasn’t really to drastically change the landscape of our primarily single-family neighborhoods,” Jason Wittenberg, the manager of Code Development for the City of Minneapolis, tells ARLnow. “It was always our expectation that duplexes and triplexes would be added in a very incremental way, which is how that has played out.”

He noted that both proponents and opponents “are a little surprised by the fact that it’s not a real rapid change.”

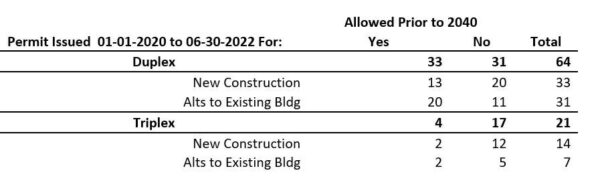

In a typical year, Minneapolis grants permits for over 3,000 new housing units. The 64 duplexes, or 128 units, built over the past 2.5 years as a result of the zoning change are “a small fraction of the overall housing supply,” Wittenberg said.

“Our feeling is that this is not insignificant,” he said. “Over time, that’s hundreds of units between now and 2040 that wouldn’t have existed.”

Meanwhile, there’s been a drop in single-family home construction, which predated the adoption of the new zoning laws and likely had to do with the pandemic, civic unrest in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, supply chain shortages and rising construction costs, Wittenberg said.

This “it’s more than the status quo” sentiment is shared in Portland.

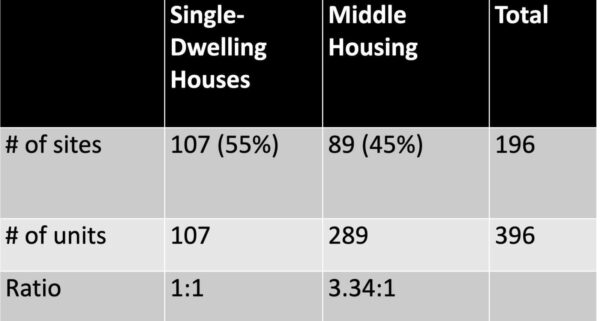

From Aug. 1, 2021 to Aug. 1, 2022, slightly less than half of new development consisted of “middle housing,” according to a presentation by city planner Sandra Wood during a conference hosted at George Mason University earlier this month.

Of the 196 sites developed or redeveloped, 89 had two to four units on them, yielding 289 units.

“Two hundred more units were built on those middle housing sites than would otherwise have been built, had this all been redeveloped, they would’ve just been single-family houses,” Wood said at the time.

That fits with the overarching reason for the zoning changes in Portland.

“Overall, what we’re aiming for is to increase access to more types of housing in all Portland neighborhoods, allowing more units at lower prices on every lot, and applying new limits to the building scale and heights and reducing displacement overall, which we don’t know the results of yet, but we will be monitoring,” Wood said.

The most common new housing type in Minneapolis is the duplex. About half of duplexes were built in zones that were formerly restricted to single-family homes, Wittenberg said.

Meanwhile, the most common “middle” housing type in Portland is a quadplex.

“We expected duplexes might be because of our small site sizes but fourplexes have outstripped duplexes by quite a bit,” Wood said.

Prior to the ordinance updates, Portland’s lowest-density neighborhoods allowed single-family homes, accessory dwelling units and corner-lot duplexes. The ADU program has been successful, she said, with 5,000 ADUs built so far.

Similar ADUs have started popping up in Arlington since the Arlington County Board approved them in 2019, but developers and economists say the building rate has been hampered by county policies and financing hurdles.

Similar policies

Density, size and parking are just some of the concerns Arlingtonians have expressed as the county hammers out a draft Missing Middle proposal for consideration.

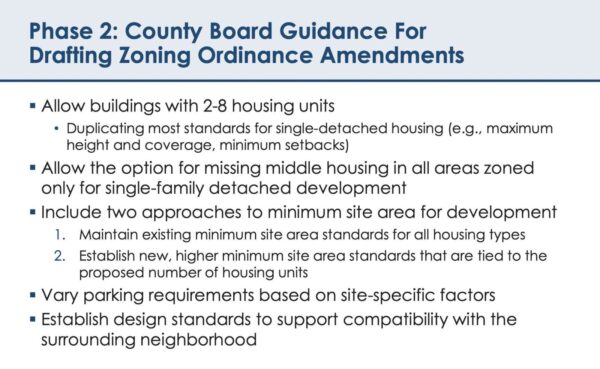

The current proposal on the table would be to allow two- to eight-unit buildings on lots that are exclusively zoned for single-family homes, in the existing footprint allowed for single-family homes. Staff are hammering out the exact details on building size and parking based on guidance the Arlington County Board issued this summer.

Both Portland and Minneapolis tackled these issues in their amendments.

Portland’s floor-area ratio (FAR) is calculated by a sliding scale based on the number of units, with bonus area allotted if any of the units are deemed affordable. Minneapolis says the floor-area ratio cannot exceed the maximum allowed for single-family dwellings.

They both limit density, too, and allow fewer units per building than Arlington’s current proposal.

Portland allows up to four units, but six can be built if half are committed affordable dwellings and two are “visitable” for people with limited mobility. In Minneapolis, the upper limit is a triplex.

“There was a sense that four-unit buildings wouldn’t fit particularly well on standard sized Minneapolis lots,” Wittenberg said. “It’s tough enough to fit a triplex on that lot, within the allowed envelop.”

Mostly, triplexes have two above-ground units and one garden-level or basement unit, he said.

Both cities eliminated off-street parking requirements so that builders did not have to include a garage or driveway.

Tree canopy and concentration

One major concern for local Missing Middle opponents is the impact on tree canopy. The group Arlingtonians for Our Sustainable Future released a report claiming that, based on information it requested from the county, many “Missing Middle” lots won’t meet county tree canopy requirements.

Arlington County is still hammering out its approach to site coverage, per a presentation to the Long Range Planning Committee on Oct. 17.

In Minneapolis, Wittenberg said this issue is addressed by a requirement that there is at least one tree per 3,000 square feet of area not occupied by buildings.

Minneapolis has not studied the impact on tree canopy, but Wittenberg said floor-area ratio requirements and the city’s tree ordinance keep clear-cutting to a minimum.

“In our lowest density zoned districts, previously reserved for single family homes, we’ve limited the scale and bulk of duplexes and triplexes to be the same as the limit on single-family homes. That would be an indication there has been no real impact on things like tree canopy and impervious surfaces,” he said.

Portland has noted a drop in tree canopy but has not studied its causes.

A tree canopy study for Portland found that the city’s tree canopy has shrunk from 30.7% to 29.8% — the equivalent of 823 acres — since 2015.

While the numbers are within the margin of error, and could be statistically insignificant, they could be part of a trend, local newspaper Willamette Week reports. The study did not look into reasons for the shrinkage, saying that would be an area for future study, but did suggest bad weather, development and death by pests could be to blame.

Another area of concern, for some residents of Arlington neighborhoods that still retain some lower-cost homeownership opportunities, is that development will be concentrated where land values are lower, and housing diversity already exists, such as the Halls Hill neighborhood. Advocates from Halls Hill told ARLnow that the county should do more to ensure that the construction is distributed throughout the county.

In Minneapolis and Portland, certain pockets are seeing more redevelopment than others.

In Minneapolis, Wittenberg said, most of the “middle housing” construction is clustered around the University of Minnesota.

“The economics of that tend to be more favorable than developing in other parts of the city,” he said.

Meanwhile, most of the “Missing Middle” construction in Portland has been in its more working-class neighborhoods, where land values are cheaper, Wood told ARLnow after the conference.

The Arlington County Board has asked staff to develop draft zoning text and land use plan amendments for consideration by both the Planning Commission and County Board as early as later this year.