The informal, relationships-based advocacy at the core of the “Arlington Way” makes it harder for nonprofits led by and serving people of color to receive county funding, Arlington County Board Chair Katie Cristol says.

She tells ARLnow these concerns were raised by leaders of color, and she is working on a resolution — that could be voted on by the County Board this month — to change the status quo. The resolution will incorporate recommendations made by a small group of leaders representing local nonprofits.

At the top of their list is a fairly simple concept: a formal application process. Right now, Cristol says, the county uses an “ad hoc” process that doesn’t “live up to our values of transparency and access.”

Meanwhile, a decades-old, community-based program that identifies small infrastructure improvements is confronting a longstanding criticism — which leadership says is backed up by fresh data — of favoring projects in wealthier, whiter neighborhoods.

Community leaders presented updates on these efforts to the Arlington County Board last month. The moves are part of the county’s work to apply its 2019 equity resolution to policy-making and the newest contribution to the Board’s ongoing discussion of problems with the “Arlington Way,” the moniker given to the public process that informs policy-making.

The process often rewards those who are most civically active, connected and vocal about a given issue. But not always: it also frustrates those who follow the civic engagement playbook only to have the Board vote the other way.

“We heard some truthful feedback about how the ‘Arlington Way’ — for the many things it has achieved and its, at times, positive contributions to the community — also has some real downsides,” Cristol said in the Dec. 20, 2022 meeting. “It has been a way of doing things that lacked transparency and access, has prioritized relationships over fairness, and at times, it feels like it is reflective of predetermined outcomes.”

As part of the annual budget, the county awards grants of up to $50,000 or $100,000 for nonprofits serving low- and moderate-income residents, such as employment programs for people with disabilities, after-school programming for immigrant youth and financial planning assistance for families at risk of homelessness.

Leaders of local organizations say the county needs to do a better job of publicizing when funding is available and helping grassroots groups with the application process.

“This part was important for us, particularly for smaller organizations who don’t necessarily have the bandwidth or knowledge in the grant-making cycle that other larger organizations have,” said Cicely Whitfield, the chief program officer for the homeless shelter Bridges to Independence.

This could involve providing clearer deadlines and technical assistance, as well as feedback and workshop opportunities for nonprofits that are denied funding so they can apply successfully.

The group says the county should defer to organizations, which have a better sense of what the community needs, and ask for input on applications from people who would benefit.

Board Member Libby Garvey supported the changes but warned they could be controversial.

“There’s that saying, ‘I’m here from the government and I’m here to help you,’ and that’s supposed to be scary. It’s really because what it often means is, ‘I’m here from the government and I’m here to tell you what you need.'”

The sentiment applies to the Arlington Way, she says.

“We may find a little reaction from this, that ‘This is not the Arlington Way,'” she said. “We’re going to have to figure out ways to bring along everyone and explain… ‘This is going to be better and here’s why.’ We’re going to have work to do with the other part of the community that maybe is usually included.”

There is a three-decade-old program where the county acts on needs identified by residents: the Arlington Neighborhood Conservation Program, now known as the Arlington Neighborhoods Program (ANP).

The downside of this program is that it has “equity liabilities,” County Board Member Takis Karantonis said.

He said the model works for “community members who could afford to go to the meetings, who could afford to make a methodical evaluation of the state of sidewalks, or lack of sidewalks, or lack of public lighting… and fight for funding in a competitive but orderly manner.”

Although not a new criticism, ANP Chair Kathy Reeder provided the County Board with new data suggesting the program has disadvantaged less wealthy, more diverse neighborhoods.

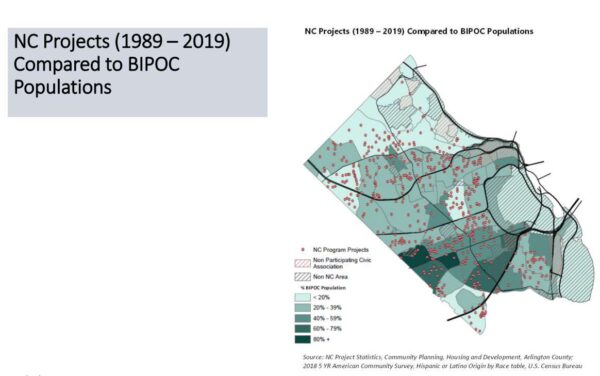

Reeder said a review of projects from 1989 to 2019 found areas with the greatest concentrations of people of color received 8% of projects, compared to areas with the lowest concentrations of people of color, which got 20% of projects.

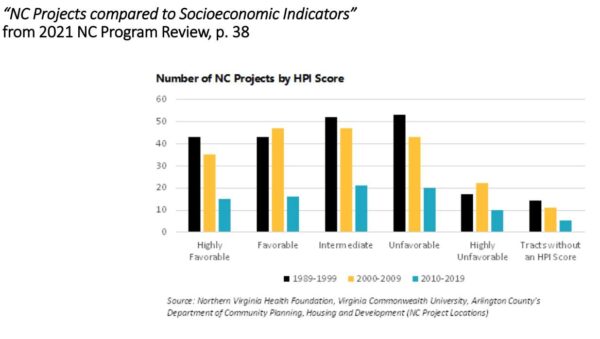

Additionally, neighborhoods with the highest renter and poverty rates and the lowest higher-education and English proficiency rates — labeled as “highly unfavorable” on the “healthy places index” — have historically received the fewest projects, she said.

Reeder said evaluations of new projects will include two additional criteria: first, whether the neighborhood has a high population of people of color, and second, whether it has high rates of poverty and low rates of higher education, homeownership and English proficiency.

These changes come on the heels of the program’s decision to ditch “conservation” in its name on the grounds that it “often evokes a negative connotation and suggests exclusivity.”

“It’s been really nice to see ArNAC embrace equity as so core as the program has been relaunched and reconceived its own future,” Cristol said.

There will be a meeting on Monday at the Lubber Run Community Center at 6:30 p.m to present the recommendations for nonprofit funding changes. By then, Cristol said there should be a county webpage explaining the changes and providing an implementation timeline.