The following was funded, in part, by the ARLnow Press Club. Become a member today and support in-depth local reporting.

In Arlington and across the state, hospital emergency rooms are filling up with people in mental health crises, often handcuffed to gurneys and attended by law enforcement officers.

People in these situations can’t walk around, save to go to the bathroom, and they can’t see their families. They may be calm or exhibiting aggressive behaviors; they might be hearing voices or may not have eaten in days because they believe their food is poisoned.

Whatever the case, they are in the emergency room because local clinicians determined they are a danger to themselves or others or unable to care for themselves, and need to be treated by specialized staff in a hospital.

Magistrates placed them under the civil custody of law enforcement officers, who have to stay with them until ER nurses can conduct a basic physical exam and clear them to go to that hospital’s behavioral health ward, where they will receive additional treatment.

That is how it should work.

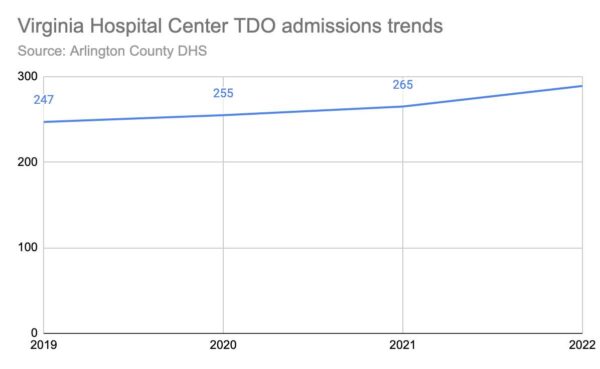

But a statewide shortage of adult psychiatric beds means people in crisis — and under either an eight-hour emergency custody orders (ECOs) or 72-hour temporary detention orders (TDOs) — could wait hours under the eye of law enforcement for medical clearance while local social workers call every hospital in the state searching for beds. Once beds are located, police will drive their charges there — sometimes up to five hours away.

The shortage is straining Virginia’s mental health care system, which is held up by dwindling ranks of under-resourced clinicians, nurses and law enforcement working overtime.

“You do wonder, how much is this helping this person as opposed to hurting someone?” said police officer James Herring, who is running for Arlington County Sheriff. “This ‘help’ feels very, ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.’ That’s not what any of us wants, but it’s the way the system has evolved.”

The current crisis is a result of the state’s decision in 2021 to close most state psychiatric hospitals, which were understaffed due to low wages, hazardous working conditions and Covid. This took some 260 psychiatric beds offline, resulting in people across the state being diverted to remaining state facilities, including Northern Virginia Mental Health Institute, where many Arlington patients go.

The bed shortage has prompted Arlington County law enforcement agencies, the Dept. of Human Services and Community Services Board and VHC Health — the new name of Virginia Hospital Center — to work together to move away from a system that they say causes trauma and pulls officers away from important duties and toward a community-based continuum of care.

Just yesterday (Tuesday), VHC announced it will be building a facility dedicated to behavioral health at its former urgent care facility at 601 S. Carlin Springs Road.

“The crisis with the state hospital beds has forced us, locally and regionally, to bust our butt to come up with [ways to] help people who are in crisis,” says Deborah Warren, the executive director of the Arlington Community Services Board and the DHS Deputy Director.

Other events threw these systemic issues into relief, too, Warren says. The Richmond police shooting of Marcus-David Peters, who was having a psychotic episode, demonstrated the risk of police responding to a behavioral health problem while pandemic-era isolation has made mental illnesses more acute.

“It’s true for every population and age band,” Warren said. “People aren’t doing well, post-pandemic… Anybody can go into a behavioral health crisis… It’s neurotypical people who are overwhelmed and overrun with feelings of anxiety and depression… People are more self-destructive. It’s gut-wrenching.”

Last year, the Virginia legislature directed the state Dept. of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services to discuss alternatives to police transportation, with stakeholders that included Arlington police, says ACPD spokeswoman Ashley Savage. The workgroup came up with the idea for the Prompt Placement Task Force, which brings together government agencies, public and private hospitals, law enforcement and community partners to address the crisis.

Gov. Glenn Youngkin announced the creation of this task force, of which Warren is a member, in December 2022. The goal is to come up with solutions that could be enacted this legislative session.

But the problem won’t get better until every locality has more services upstream, said state Sen. Barbara Favola, who noted Arlington has “more community-based care than most parts of the state.”

“Virginia has more people in psych beds than need to be there because we don’t have a community-based network to release them into care,” she said.

Getting by

Historically, Virginia mostly funded state facilities and wealthy jurisdictions in Northern Virginia, like Arlington County, applied local tax dollars to their community services boards, explains Warren. But as evidenced by the current crisis, even Arlington has room to improve.

“We have a long way to go, and the state has a long way to go,” she said.

Currently, people are taken to the hospital under an emergency custody order (ECO) to be evaluated for the longer, three-day order — the temporary detention order — under which they are able to get more treatment at a hospital.

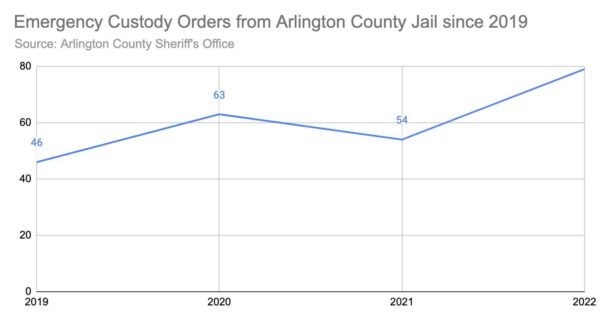

This process often starts with an evaluation by county social workers at the Arlington County Detention Facility, where Sheriff’s Office spokeswoman Maj. Tara Johnson says there are “a significant amount of individuals in our custody with serious mental illness.”

Two sheriffs will take someone under an ECO to the hospital, and one can return if the person seems calm. In 2022, the longest sheriffs had to wait with someone for a bed was five days, or 113.5 man-hours. During the same period, sheriffs spent nearly 1828 total man-hours at the hospital, she said.

Sometimes people show up at the Arlington’s Crisis Intervention Center within the county’s health facilities at Sequoia Plaza (2100 Washington Blvd). This five-room calming center has hospital-grade recliners, neutral colors, a shower and bathroom, clinicians on staff and a pharmacy upstairs. Staff there try to avoid sending the person to the hospital, if feasible.

“People’s presentations can be fluid,” said licensed Arlington County social worker Katelyn Riemer. “There could be situations where there here in the office with us and we can de-escalate and bring them down a couple notches so they’re not meeting criteria, or we can wrap in different community resources or supports, family, friends, shelters, different resources that can reduce their risk so they don’t need to go to the hospital. That’s the goal.”

But if they have to go to the hospital, and there are no beds, “we will keep pushing through,” Riemer says. That includes working with a crisis receiving center in Chantilly for temporary placement.

Driving patients to the ER and sitting with them, then driving them to the hospital or these receiving centers, is a significant drain on law enforcement.

To alleviate the impact of the crisis on police staffing, Savage said “the department has created alternative transport, an overtime detail of officers solely dedicated to the transport and custody of patients.”

Officer Herring says it’s hard to find people willing to work overtime, however, “because you don’t know when your day will end.”

The situation is just as difficult inside the jail, according to Maj. Johnson.

“We are coping by modifying operations of the facility — canceling programs and visiting and lessening out-of-cell time — pulling staff from other divisions, and mandating overtime,” she said.

Riemer says she wants to keep vulnerable people prone to overstimulation from lying on a gurney in a hospital hallway, exposed to “nonstop noise, nonstop stimulation, lights” while nurses draw their blood or perform other tests.

“I would really love to build up our crisis intervention center to be able to accommodate medical clearance,” she said.

That is just one solution among many Warren says she and the county’s Dept. of Human Services, with support from the Arlington County Board, are pursuing.

Solutions

DHS aims to remove law enforcement from the process and keep people out of the hospital, or jail, where possible, Warren says.

The first point of diversion is the county’s alert system for sifting through calls to 911 or 988 — a new national suicide and mental health crisis hotline — to determine what kind of response is needed.

That could be the Community Regional Crisis Response (CR2), 24-hour rapid response team that handles people of all ages facing a mental health or substance use crisis. Or, once they are operational this spring, mobile crisis response vans that shuttle clinicians to behavioral health emergencies.

If law enforcement does have to respond, Warren’s goal is to make sure all personnel are trained in de-escalation and taught techniques for handling different situations, such as someone with autism or someone who hears voices. About half of Arlington officers have this training.

“The silver lining in this [crisis] is that more and more folks, now, when they’re displaying behaviors that would be odd or potentially violent, the police are now more aware that these folks are suffering from a mental health crisis and shouldn’t be jailed,” Favola said.

Warren also wants people coming to the Sequoia facility, which is going through the process of getting a license to allow people to stay for up to 23 hours. Soon, it will also have security guards authorized by a judge and the Arlington County Chief of Police to accept people under temporary detention orders and transport them to a hospital.

“Our vision is that this will save law enforcement substantial time and money long term, in terms of overtime,” she said.

Favola said she has a bill that “essentially would require hospitals to come up with trauma-informed security, which would be the first step in the goal of removing police of the liability of staying with this individual.”

Because increasing hospital capacity can take years, in the interim, municipalities in the region are adding more crisis receiving centers, which have beds and can hold people under TDOs. Meanwhile, hospitals in the region are looking at administering treatment and conducting assessments in the ER.

VHC Health plans to build the new facility at the 601 S. Carlin Springs Road property with 72 beds dedicated to mental health and substance use recovery. This consists of a 24-bed adult unit, a 24-bed youth unit, a 24-bed “recovery and wellness unit” and five outpatient programs. It will have 40 beds set aside for people with brain and spinal cord injuries, those recovering from strokes and those with neurological and other conditions.

In addition, Warren told ARLnow earlier this month that VHC will be updating its emergency room to include eight “safe space” bays for individuals in psychiatric crisis, three private calming rooms and a shower and bathroom to the emergency room.

“They are the best possible partners we could have,” Warren said. “They have been wonderful about working with us on this problem.”

The state hospital closures forced localities, including private hospitals, to step up. After 50 years in the mental health field, Warren thinks the crisis has sent communities in the right direction.

“State hospitals can be scary places, being in a place where the whole building is behavioral health,” she said. “I like the idea of units in community hospitals: you’re home, you’re near your family, your family can come visit you during visiting hours, your family can come participate in therapy. You’re connected to your community.”