(Updated at 12:30 p.m.) A year ago, Arlington County launched a diversion program for youth and young adults who commit certain misdemeanor and felony crimes.

Heart of Safety is a voluntary program facilitated by Restorative Arlington, a nonprofit that facilitates meetings between victims who choose this approach and the people who committed crimes against them.

The Commonwealth’s Attorney or the local court services unit — which provides services to juvenile court-involved youth and their families — refers victims of crimes who want to stay out of court proceedings to the program.

There, victims and the people who harmed them meet with facilitators and each other to discuss what happened and why, the results of that crime and how the perpetrator can make amends — typically by adhering to a restoration plan to which both parties agree. This approach borrows from longstanding indigenous traditions that have been implemented and studied in some U.S. communities.

The Office of the Commonwealth’s Attorney has referred eight cases to the program as of November. That figure comes from a Freedom of Information Act request filed last fall by the campaign to elect Josh Katcher, challenger to Commonwealth’s Attorney Parisa Dehghani-Tafti in the Democratic primary on June 20. His campaign released its findings on Friday.

Program Executive Director Kimiko Lighty says that the number of cases that have gone through the program is higher. It does not include cases referred from court services unit, those completed in 2022, ongoing cases, or those on who are on a six-month waitlist that she would take if the program had more capacity.

“Heart of Safety is working at capacity right now and has a waitlist,” Lighty says. “There are people who are saying, ‘We would rather wait to have a restorative option than go to court.'”

Participants include people from middle school through 26 years old who committed a fairly broad range of crimes, though Lighty did not elaborate on what kind, citing privacy.

“What they have in common, every single one, is that the person harmed asked for a restorative process,” Lighty said.

Dehghani-Tafti, elected in 2019 on a platform of prosecutorial reform, has said on the campaign trail that Heart of Safety is an avenue for victims to heal and for people who committed crimes to reckon with their actions, demonstrate remorse and commit to making amends.

She tells ARLnow the cases that went through the program “have gone really well” and been consistent with a memorandum of understanding and referral policies governing the program, both of which were provided to ARLnow.

Katcher and his team take issue with how the program has been promoted and how much credit Dehghani-Tafti can take for it, maintaining that people should be skeptical about why Dehghani-Tafti is not more forthright about program outcomes.

His team requested the number and types of cases that have gone through Heart of Safety, the number referred back to the courts, the memorandum of understanding and referral criteria governing the program, and a definition of recidivism.

In response, his campaign says it received the number of cases, eight, and the same documents Dehghani-Tafti’s campaign provided to ARLnow.

“Parisa Dehghani-Tafti wants the community to think of her as a reformer. However, when pressed for information to prove that she’s living up to our community’s expectations for what that means, her office refuses to answer basic questions around the efficacy of her highly-touted commitment to restorative justice,” the campaign manager for Katcher, Ben Jones, said in a statement.

“Her refusal to answer simple questions about a program that she has touted as being one of her signature promises is another sign that she’s not the right person to be trusted with ensuring our community’s safety and security,” he continued.

Lighty says so few cases were referred back to the court system that revealing this could also reveal personally identifiable information. Victims were also referred back after preliminary meetings but before enrolling in the program.

She aims to release more complete data in June 2024, when she hopes to have enough completed cases to respect the privacy of participants.

For now, she is frustrated with some of the negative claims, which she says lacks a principled foundation.

“It’s an effort to deny the Commonwealth’s Attorney a political win or an effort to deny victims of crime an alternative option. It’s heartbreaking to see that happen, especially when the charge is led by people who claim to support restorative justice,” she said.

“We have a ton of partners from community members to faith-based organizations to local institutions and government partners,” she continued. “I am very willing to work with anyone who is willing to support restorative justice options in Arlington and Falls Church, including community members, organizations and institutional partners.”

The bigger issue, she says, is securing funding when previous efforts have been stymied by people she says willfully misunderstand the program.

When Arlington County transitioned its restorative justice efforts from a county-run initiative to a community-based nonprofit, Lighty needed to ask the state to authorize the nonprofit to spend a grant awarded to the county.

Despite backing from the state Criminal Justice Services Board’s Grant Committee, the issue was tabled last year after a representative for Attorney General Jason Miyares objected. The representative said the program would circumvent the rights of victims to be protected and heard in a court of law.

Other sources present recalled sharper objections, alleging people who committed serious felonies could have charges diverted.

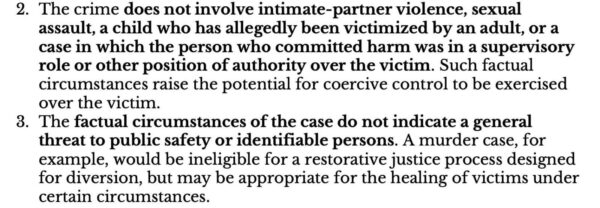

The referral requirements say otherwise, per the following excerpt.

The grant is still in limbo, according to Lighty.

This experience motivates Dehghani-Tafti, if re-elected, to advocate for steadier funding sources, including from Arlington County.

“You wouldn’t expect a business to simply get started on seed money and sustain itself after a year or two — you would need much more time to deepen its roots,” she said. “It’s the same issue here.”

This article has been updated to reflect that another Arlington-area nonprofit, Center for Youth and Family Advocacy, has an agreement with Arlington County to use restorative practices in diversion programs.