For the last decade, Arlington Public Schools has tried to increase the time students with disabilities spend with their typically abled peers.

Creating a more inclusive environment can benefit students with disabilities and their peers, according to some studies — though not all — as well as new APS academic data. But it is easier said than done.

As of the 2020-21 school year, 67% of students with disabilities spent 80% of their time in the general education setting. The students who make up the difference might spend more time in a small-group setting or they may be placed in county-wide programs.

The 67% figure put APS 5 percentage points below state targets that year and 13 percentage points below a goal it set in its 2018-24 strategic plan.

Progress toward this goal has been sporadic because APS lacked a concrete plan and system-wide buy in to make these changes, according to old APS reports and interviews ARLnow conducted.

“The basic punchline is that they set the goal… and then they didn’t do anything differently for the subsequent five-plus years,” says parent David Rosenblatt, the former chair of Arlington Special Education Advisory Committee. “There was no meaningful plan except goals on paper.”

There are new signs of progress, though.

This year, the Office of Special Education is working with leaders of schools with inclusion rates below 65% to develop goals around increasing inclusion and strategies to help staff with this work, according to APS spokesman Frank Bellvia.

APS is in the early stages of hiring a consultant to devise system-level changes. It issued a request for proposals this summer and is re-issuing a new one this fall.

Previous consultant reports from 2013 and 2019 said Arlington could improve its inclusion efforts but left it to the school system to change. The 2019 report gave APS low marks for its progress since 2013.

APS confirmed its 2024 goal will transfer to future strategic plans.

“Supporting our [students with disabilities] is a core value for the district, and it will take some time to achieve this goal as it involves several factors,” Bellavia said. “Some of these include building an inclusive mindset with staff and within the community, staffing needs, and master schedules at the school.”

What inclusion looks like today

For APS, the good news is that, in 2019, a majority of students receiving services for their disability said they were treated fairly, welcomed in school and able to participate in afterschool activities.

On the other hand, 30% said this was not their experience and 35% said only some or none of their teachers have high expectations for them or “that they don’t know,” per the report.

For special education attorney Juliet Hiznay, students with disabilities can benefit from the higher expectations set in general education classrooms than in separate programs.

“The rationale for [these programs] is that they need a lower ratio, fewer distractions, modified curriculum,” she says. “The problem with that is that we’re looking at supporting a programmatic model rather than taking the student and saying, ‘How do we include her? What is she capable of?’”

Separate tracks may also contribute to fewer general education teachers who receive sufficient training to teach students with disabilities. The 2019 report found only 45% of general education teachers felt equipped to teach this population.

Annually, APS reports to the state how much time students with disabilities spend in with their typically abled peers in general education classrooms, as well as at lunch, recess, study periods, libraries and field trips.

Over the last four years, 13 schools have, like APS, seen increasing inclusion rates, while another 12 have seen decreased inclusion rates, according to data provided by the Arlington Inclusion Task Force, aimed at increasing inclusion in APS.

APS monitors a dozen schools with rates below 65%, which also tend to be schools that host county-wide programs.

Those with low rates are: Alice West Fleet, Arlington Science Focus, Campbell, Drew and Long Branch elementary schools, Jefferson and Kenmore middle schools and Wakefield and Washington-Liberty high schools. This information was obtained by a Freedom of Information request by the Arlington Special Education PTA Advocacy Committee and shared with the inclusion task force.

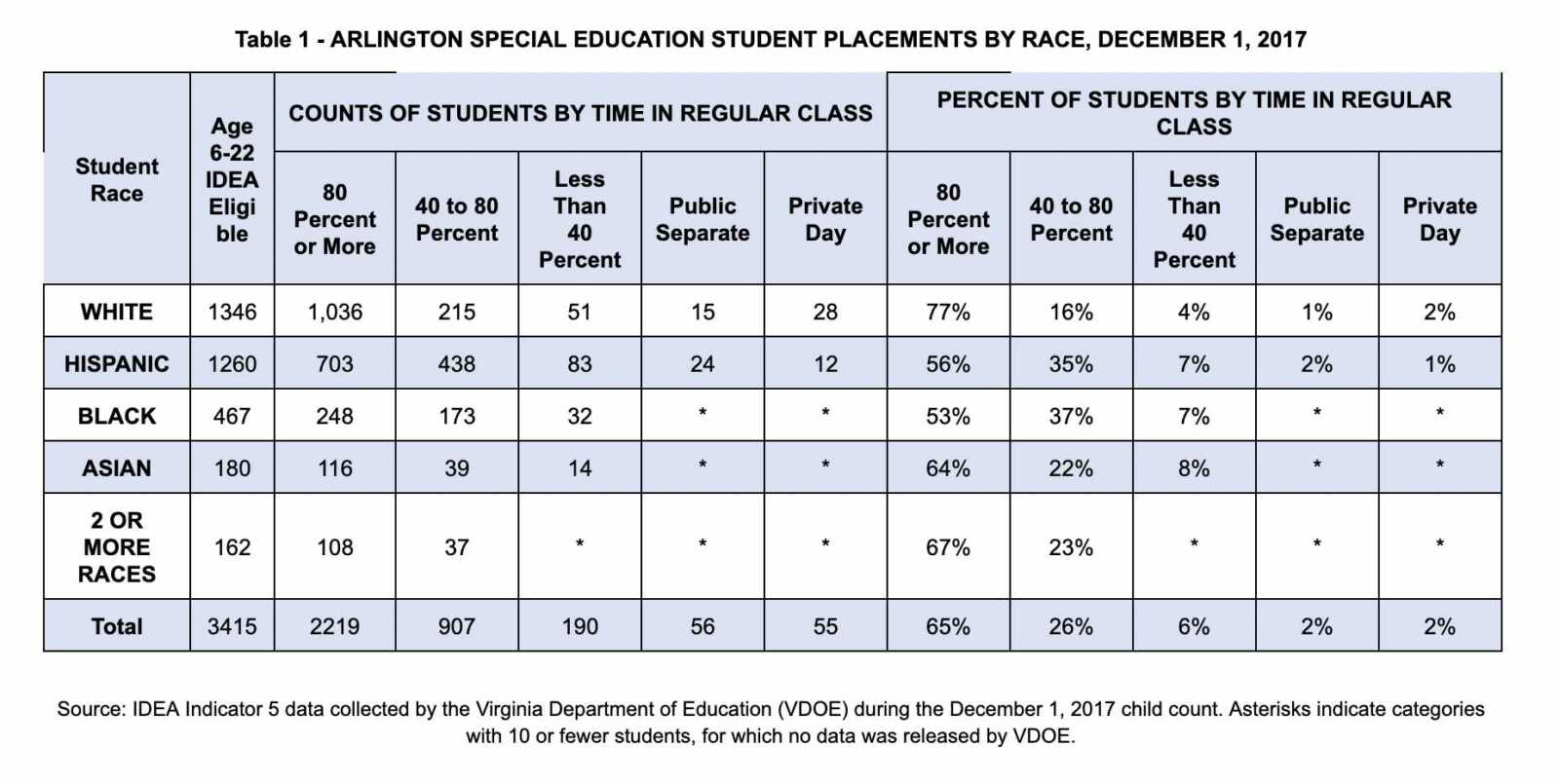

Inclusion rates also vary by race and ethnicity.

“Our goal is 80% of students, 80% of the day. That’s [almost] true for white students but it is not true for Black and Latino students with disabilities,” Rosenblatt said. “They’re dramatically more likely to be placed in segregated settings.”

What inclusion could look like

APS is seeing at least one fruit of inclusion: rising state test scores among some students with disabilities.

On recent state tests, those placed in classes co-taught by by general- and special-education teachers fared better than students in self-contained classrooms, Chief Academic Officer Dr. Gerald Mann, Jr. told the School Board this month.

School Board member Mary Kadera said this “reinforces the belief that many of us have that it’s important, for many reasons, that we push forward with that goal of inclusion.”

Inclusion, as a goal, has been championed by some parents for decades.

Nearly 20 years ago, for instance, a special education committee recommended that APS add books on inclusion to libraries and mandate inclusion training for staff, but these were struck down by the Committee on Instruction.

“A good inclusive classroom supports and benefits all learners. A good inclusive school has committed leadership, reflective teachers, and a supportive culture,” the report said.

Rosenblatt echoed these comments, saying that in inclusive classes, anyone can benefit from the support team attached to students with disabilities.

“A paraprofessional who goes to support [a student with disabilities] supports other kids,” he said. “A speech therapist will engage other kids. A special educator will engage other kids. There’s more resources in that classroom… [where] there are a lot of kids who may not have official labels or diagnoses.”

A success story — and a long road ahead

Twenty years ago, Cecil County Public Schools in Maryland bussed all its students with disabilities to specialized programs. Now, around 90% of students spend at least 80% of their time in the general education setting.

It made that progress working with the Maryland Coalition for Inclusive Education (MCIE), which works with Maryland school districts to improve their inclusion rates.

MCIE Communications Director Tim Villegas says in Cecil, the inclusion is thoughtful and oriented toward ensuring students are physically present, feel membership, participate meaningfully and learn the same content.

This transition can work for students of all ages, even teens coming from special programs, he says.

Villegas recalls a sophomore who moved from a specialized program to his home school, made friends and experienced higher academic standards from new teachers.

“That increased his quality of life… He became part of the football team and part of the life of the school,” Villegas said.

But growth can be plagued by setbacks, only overcome with commitment from the top, Villegas said.

“I think the biggest thing for us is that among leadership — and I’m talking about the superintendent, the assistant superintendent, the directors of curriculum — there’s a commitment at the very top that this is important work,” he said.

APS likewise says this work will take time. It says a system-level commitment should trickle down to school-level conversations about how school leaders can improve inclusion next year and going forward.

“This strategic goal is not meant to be a blanket change for all students all at once, but a thoughtful and intentional student by student determination,” Bellavia said.

The following in-depth local reporting was supported by the ARLnow Press Club. Join to support local journalism and to get an early look at what we’re planning to cover each day.