This reporting was supported by the ARLnow Press Club. Join today to support in-depth local journalism — and get an exclusive morning preview of each day’s planned coverage.

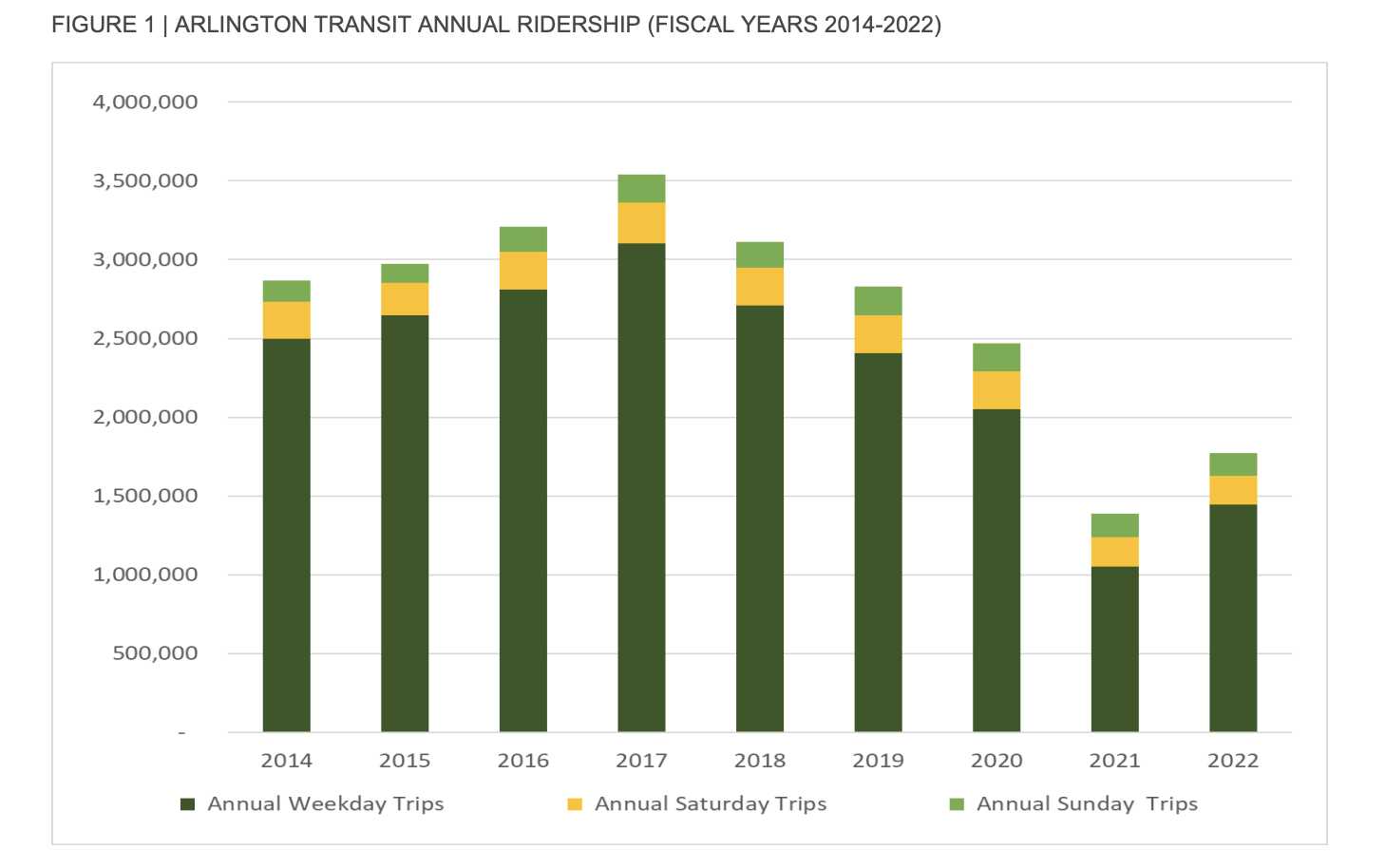

(Updated at 4:15 p.m.) In the half-decade leading up to 2017, ridership on Arlington Transit, or ART, had risen 34%, or nearly 1 million rides.

Then, in 2018, ridership started trending down, a decline that Covid only sped up — despite the essential workers who continued riding the bus and insulated ART from the pandemic hit Metro sustained.

Today, ridership is on the upswing but still far lower than the 2017 highs. Arlington County is trying to change that — outlining several service changes in a new 10-year strategic plan — all while studying how best to make more expensive investments: buying zero-emission buses.

As for ridership, Joan McIntyre — chair of Arlington’s Climate Change, Energy and Environment Commission, or C2E2 — attributes low numbers to the length of time it takes to reach many destinations in Arlington by bus versus by car.

“Even before the pandemic, ridership of ART and other public transit was largely stagnant,” she told the County Board last month in November. “The reality is that for many in Arlington, you simply can’t get there from here via public transit.”

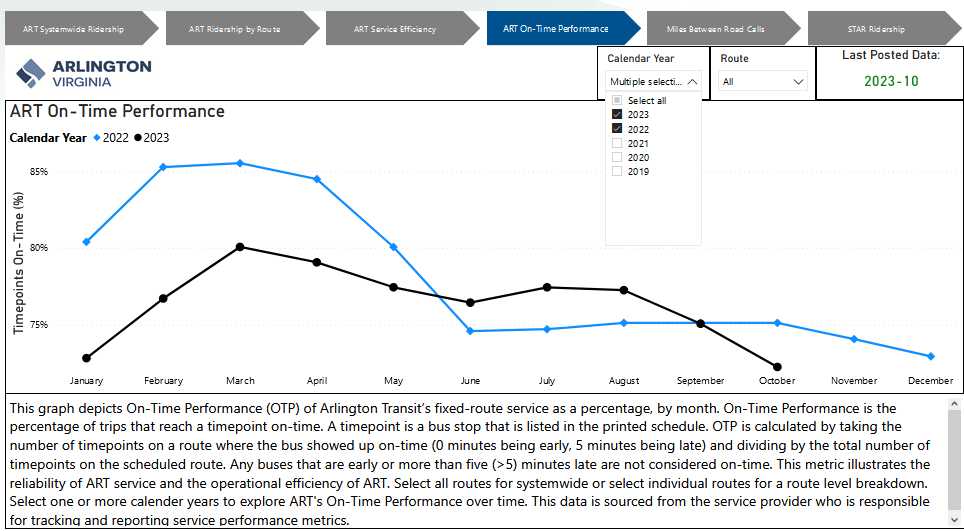

Surveyed as this plan was coming together, Arlingtonians said the bus needs to arrive more frequently, run for more hours and connect them to more destinations. A 2019 study diagnosing ART’s declining ridership found riders wanted more frequent service, better real-time information and more on-time performance. A 2022 survey had similar findings.

Arlington was not alone in seeing a pre-Covid ridership slump and national studies found contributing factors included the rise of telework, online shopping and ride-hailing services, lower gas prices and higher fares, and in New York and D.C., maintenance service disruptions. (Arlington’s 2019 survey likewise found ride-hailing siphoned off some 19% riders while 51% only rode for work, suggesting telework could be a limiting factor today.)

Arlington cannot control for telework and ride-hailing, but it can make service changes. Areas with growing ridership, Columbia Pike and Route 1, are set to see more frequent service, with more weekend trips and new destinations, such as Long Bridge Park.

Expensive, low-performing routes primarily serving North Arlington will be discontinued or redrawn to connect high-ridership neighborhoods and destinations, such as Waverly Hills and Virginia Hospital Center. Where service is discontinued, it intends to pilot an on-demand “microtransit” option.

On-time performance, however, has more external factors to consider. Recently, this includes public and private construction on Columbia Pike and near the Pentagon, which the county considers “temporary disruptions for long-term gain.” Other factors are traffic congestion on I-395 and in Pentagon City and, for a more positive spin, increased ridership on several routes.

To make every change outlined in the 10-year plan, Arlington County would need to spend some $10 million, according to Transit Bureau Chief Lynn Rivers.

This is a fraction of the $130-$180 million estimate from a consulting firm that analyzed the potential cost to convert the entire ART bus fleet to battery electric or hydrogen fuel cell electric buses, though advocates say up to two-thirds of purchase costs could come from state and national funds.

High-dollar investments in buses are not without their controversies. A decade ago, Arlington and Metro embarked on installing new stops on Columbia Pike, leading with the memorable $1 million Pike “Super Stop” plagued by poor inter-agency communication and design flaws.

Pilot projects like free fares, currently being tested out on all routes in peak directions, are also not guaranteed successes. Arlington is currently piloting the change on the heels of some U.S. cities. Earlier European adopters, meanwhile, have reported ridership increases after going fare free but only marginal declines — and in some cases increases — in car use.

Regardless of approach, the county will have to focus on recuperating the 74% of so-called “choice riders,” or those who can drive and afford a car, from before the pandemic. The question then becomes how to get those riders to choose ART once more.

“The very big issue… is how does this entice those who are choice riders — who have other choices and we want them to make the choice to ride public transit?” County Board member Takis Karantonis said during a discussion of the transit strategic plan.

“I think this plan, at this moment, offers the best we can afford to offer,” he continued. “It is going to be a very interesting next one to two years to observe how the system actually reacts to these to these changes.”

But if route and frequency changes are the bread and butter of service changes to improve satisfaction, microtransit and cutting-edge zero-emission fuel alternatives are like dessert or exotic fruit: attention-grabbing, polarizing and expensive.

The case for and against microtransit

Route 53 connects East Falls Church and Ballston by way of Williamsburg Blvd and Military Road. It sees about 33 riders a day, costs $66 per rider to operate and, after revenue, requires a nearly $65 per rider subsidy.

It is a hard sell based on cost and the county says it does not track passenger-miles per gallon, a metric that is used to compare the efficiency of various travel modes. (Available federal data suggests that buses operating at high capacity are three times as efficient as single-occupancy cars, though that efficiency drops off with fewer riders.)

Route 53 and others serving Virginia Hospital Center, one of the biggest ridership drivers in North Arlington, are set to be reconfigured to absorb other routes the county plans to discontinue. Meanwhile, in some areas where buses will not run, Arlington proposes replacing bus service with microtransit as soon as 2027.

Arlington has mulled microtransit for several years, studying peer jurisdictions that piloted micro-transit with the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments. Years later, some of those jurisdictions maintain successful programs, while others are paused or defunct.

West Sacramento launched its ongoing microtransit initiative in 2018. Last fiscal year, it completed an average of 593 daily rides on weekdays and the city is spending about $15 per ride, or $3 million a year on the service. Where Arlington intends to use microtransit, the county spends $66-77 per rider and daily ridership is in the teens to 30s.

A shared-ride shuttle service in Austin, Texas saw about 811 weekday boardings in the 2022 fiscal year. The city, which budgeted $8.7 million for the service this fiscal year, has added vans and operating zones in response to demand, though there are some reported issues with performance and long wait times.

Arlington, Texas replaced its traditional downtown bus line with microtransit in 2017 and is now expanding the service, which has provided more than 1 million rides since its start. Some residents report poor reliability and driver behavior and lament that it should not have fully replaced buses.

Microtransit in California’s Contra Costa County has been suspended since Covid while Florida’s Hillsborough County microtransit option does not appear to exist anymore, though the agency operates a somewhat similar fixed-route option during working hours on weekdays.

While not part of the study, Fairfax County has also tested out microtransit. The $510,000 autonomous vehicle pilot, primarily funded by the state, took about 370 riders between the Mosaic District and the Dunn Loring Metro station.

Ridership was lower than projected due to Covid, says Freddy Serrano, the head of communications for the Fairfax County Dept. of Transportation. Still, Fairfax is exploring the feasibility of incorporating autonomous cars and microtransit, specifically for the Franconia and Springfield area.

“This assessment is particularly relevant for areas currently underserved by traditional transit, aiming to address mobility gaps and enhance transportation accessibility for residents,” Serrano said.

Microtransit has its critics, from New York City-based advocacy group Transit Center to the local Sustainable Mobility of Arlington. They point to pilots like these to argue microtransit does not work, is more expensive than conventional buses and distracts transit agencies from improving core services.

Rivers acknowledges microtransit is more expensive than a fixed-route bus but says the alternative serves transit-reliant people who lose their bus route due to low ridership while getting drivers more accustomed to public transit.

“It always works initially because you’re still servicing people who need who need the service,” she said. “But it gets to a point that it gets to be so many people that you move back into fixed-route service again.”

It has morphed over time to resemble ride-hailing platforms, she noted.

“When microtransit first came on the scene, it literally was about transit agencies buying vehicles and operating them itself,” Rivers said. “Even in the few years when we first started studying it, it has become more app-based, where you have independent companies that come in and provide that kind of service.”

The up-front investment costs to start a microtransit program, however, are small change compared to the sum the county is looking at to electrify its fleet — the next big upgrade coming for ART.

Battery-electric versus hydrogen buses

Arlington aims to operate a zero-emission bus fleet by 2038 and, to that end, has already announced the purchase of its first battery-electric buses two months ago.

In 2026, the county is also set to test two to four hydrogen fuel cell buses, a technology the consultant study says will require more upfront costs but could taper off as they would require less new infrastructure in the long run.

After these pilots, the county will decide which technology to pursue.

Some local environmentalist groups argue against the hydrogen pilot. They say Arlington is already on track to have a new bus facility in Green Valley that can accommodate battery-electric buses, which are better suited for ART’s low-speed, short, stop-and-go routes over easy terrain. (It will cost $33 million to fully outfit the new facility with charging infrastructure.)

Furthermore, they say hydrogen buses are more expensive than battery-electric buses while green hydrogen is comparatively scarce and requires significant energy to convert into fuel.

Sierra Club Potomac River Chapter Chair John Bloom says hydrogen seems cheaper, in the study, because it recommends replacing 1.6 of battery-electric buses for every methane bus, a pricey replacement ratio. He says this is an inflated ratio based on assumed conditions that would drain battery life faster than real-world conditions, including consistently cold weather, high passenger loads and small battery sizes.

Typically, Arlington has taken a more cautious approach — even electric vehicles, said C2E2 Energy Committee member Claire Noakes.

“Here, we are in this other parallel universe doing the opposite… and we’re doing it heading into a fiscal financial storm,” she said. “Suddenly, we’re projecting to be willing to spend $1.2 million on very cutting-edge, possibly not-attainable fuel-cell buses when we were not willing to pay the delta when we were flush with cash a few years ago on battery-electric [buses].”

Even battery-electric bus technology can have issues, though. One Canadian city that purchased 60 Proterra battery-electric buses says most are not fit for the roads just three years after their purchase, citing range, battery life, reliability and durability problems. Arlington tested out Proterra buses but ultimately purchased four by another American company, Gillig.

For others, the focus on battery-electric and hydrogen fuel-cell buses misses what ART needs.

“It’s insane to make this commitment and conversation without understanding, if we spent this money on [renewable natural gas] buses — where we could get more buses, with better range, for less money and lower operating costs — how many more people could we get out of their cars,” Transportation Commission Chair Chris Slatt said.

“I just feel like we are ultimately missing the forest for the trees by not looking at that other massive source of tailpipe emissions, and a very known, reliable way to reduce it, which is to give people another way to get around,” Slatt continued.