The following feature article was funded by our new Patreon community. Want to see more articles like this, exploring important local topics that don’t make our usual news coverage? Join and help fund additional local journalism in Arlington.

With Amazon hoping to open a headquarters in Arlington, Crystal City’s transportation network can’t seem to stay out of the spotlight.

Major redevelopment is coming whether or not local resistance turns the e-commerce giant away, but the attention-grabbing headlines and all-at-once infrastructure proposals don’t reveal how mobility investment is a gradual process – or how Crystal City has been steadily improving its transportation infrastructure since long before the HQ2 contest even began.

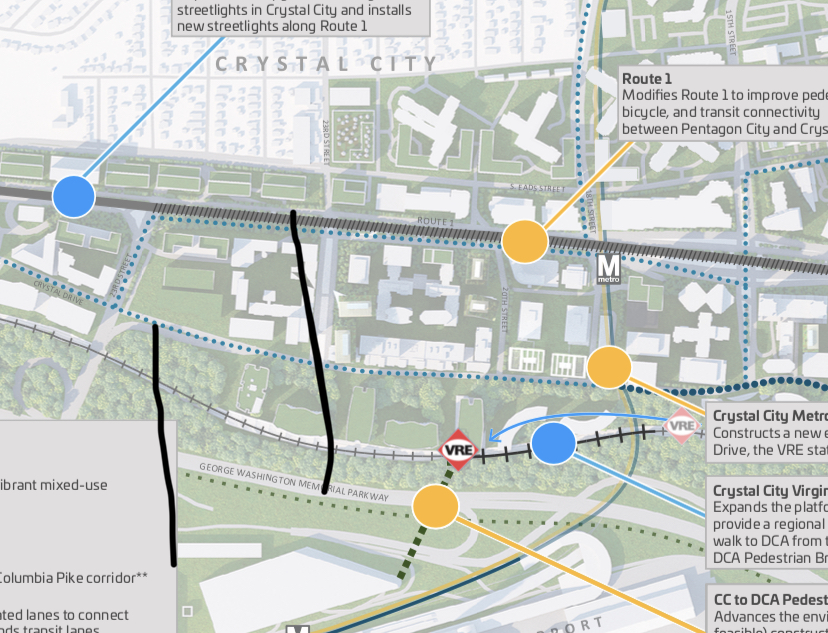

Crystal City has long been slated for some major transportation investments: Long Bridge reconstruction could enable MARC to bring commuters straight from Maryland to Crystal City and let people bicycle straight to L’Enfant Plaza. A new Metro entrance would make it much easier to connect to bus service. A remodeled VRE commuter rail station would enable larger and more trains, Metroway expansion will strengthen ties with Pentagon City and Alexandria, and a pedestrian bridge to the airport would take advantage of the fact that DCA is three times closer to Crystal City than any other airport in America is to its downtown.

These projects are big: big visibility, big impacts, big cost. They have all been in the pipeline for years, and Amazon is bringing them renewed attention and new dollars.

However, these major investments aren’t the only projects that will update Crystal City’s decades-old transportation infrastructure. Just as important as these headline-making proposals are the more incremental projects that, block by block, are making Crystal City an easier place to get around — and, just like their larger counterparts, these smaller projects have been given some extra weight by HQ2.

Old Visions, New Funding

One document has guided much of Crystal City’s development for the past decade: the Sector Plan. The Crystal City Sector Plan made many suggestions for possible improvements. Not all of them have yet come to fruition, but many have, and the plan continues to drive Arlington’s conversation about Crystal City.

That conversation has recently become a little more ambitious. Amazon’s HQ2 announcement brings not only attention, speculation and more than a little resistance — it will also bring very definite funding. Arlington and Alexandria, combined, “have secured more than $570 million in transportation funding” while the commonwealth of Virginia has committed to $195 million for the same.

This new funding flows mostly toward old designs, all of them focused on alternatives to the car. Arlington’s Incentive Proposal discusses 10 transportation “example projects.” Five of them fall within Crystal City itself, of which all but one follow ideas that originated in the Sector Plan (the remaining project, VRE station expansion, isn’t new either).

Moving Block by Block

Most of Crystal City’s streets were built in the 1950s and 1960s, and followed the “modernist” school of city planning.

They separated pedestrians from cars as much as possible, often putting pedestrians in bridges or tunnels; located stores in malls rather than on sidewalks; and spaced out intersections widely so that cars could accelerate to highway speeds. The Sector Plan calls to convert these into “Complete Streets” that will “accommodate the transportation needs of all surface transportation users, motorists, transit riders, bicyclists, and pedestrians.”

It can be easy to think of transportation investments as one-off projects. The CC2DCA pedestrian bridge to the airport, for example, is an all-or-nothing endeavor. Half of a bridge wouldn’t be very useful for anybody.

Because of its focus on the street level, the Sector Plan calls for gradual change. It endorses street transformation projects that can be completed incrementally — block by block, street by street, improving the area’s transportation network over time. It seeks “to balance any proposed investments in transportation infrastructure with improvements in the efficiency and effectiveness of the existing network, so that the maximum benefit can be delivered at the lowest cost.”

This approach pairs well with Crystal City’s desirability for land developers. Most significant developments in Arlington are governed by the site plan process, through which the county negotiates with developers for community benefits — which might include a street renovation. Robert Mandle, chief operating officer of the Crystal City Business Improvement District, explained that “as a redevelopment plan, many [Sector Plan] improvements were anticipated as occurring in conjunction with opportunities presented from redevelopment.”

For example, the Crystal Houses III residential project includes a 0.7-acre public park paid for by the developer as well as improvements to the surrounding sidewalks that will enhance pedestrian mobility.

Another example of incremental transportation investment is the conversion of Crystal Drive to a two-way street for its entire length. The process began in 2004, funded at first by a private developer, but since 2013 all work has been county-funded. It began its third and final phase of construction on Feb. 22 and is expected to be finished by December. No streets will be closed.

Mandle, of the Business Improvement District, speaks highly of the project: “improving the pedestrian streetscape and the public realm has been a key priority for all of the two-way projects, including new street trees, wider sidewalks, and bicycle infrastructure… [the projects] enabled the creation of a strong retail main street, a key amenity for attracting businesses to the area.”

Mark Schnaufer, capital projects manager for Arlington County’s transportation division, adds that the two-way project “has helped create a grid system where people have multiple options for traveling around Crystal City, providing direct access from any direction.”

Another incremental street project, also under Schnaufer’s lead, is the block-by-block creation of Clark-Bell Street. Clark-Bell will run between Route 1 and Crystal Drive, parallel to them, and help create a more mobility-friendly environment by breaking up large blocks and providing an alternate north-south path.

Because county-led projects are gradual, they’re not likely to get swept up in the excitement of sudden news. Schnaufer emphasizes that the street improvement projects “are progressing as they did before Amazon’s decision.”

However, developer-led projects like Crystal Houses III follow the private sector’s schedule — and Amazon might kick that up a gear.

Route 1: An “Urban Boulevard”?

For many Arlingtonians, the archetypal image of Crystal City is of angular brown office buildings blurring past from a driver’s seat on Route 1.

The road is legally called Jefferson Davis Highway, which Arlington can’t change because it’s under VDOT authority, and it is the central spine that reaches from Pentagon City to Alexandria. At the moment, though, this road does as much to sever as it does to connect — and the most ambitious, most important project in the Sector Plan is an attempt to change that.

Specifically, the Sector Plans calls to “[m]aintain the capacity of the current Jefferson Davis Highway while enhancing its physical environment into an urban boulevard, and direct traffic primarily to arterial streets to minimize adverse impacts of cut through traffic into surrounding neighborhoods.”

So, what does “urban boulevard” mean? It means wide, comfortable, welcoming sidewalks, bicycle and e-scooter accessibility, tearing down overpasses and designing buildings that form a natural, coherent enclosure to the street. It doesn’t mean slowing down cars — Connecticut Avenue in Northwest D.C., for example, carries similar volumes of traffic in a setting that is much for pleasant for pedestrians and bicyclists.

One major advantage of a more urban Route 1 is in the development that it will enable. By cutting off access ramps and frontage streets, and by potentially narrowing lanes, the reconstruction of this boulevard will actually free up substantial amounts of land along the sides of the street.

The Sector Plan dedicates much of this space to new development. New development brings many potential benefits — a more practical, mixed-use environment, new residential structures (perhaps for Amazon employees), and, by pressing closer to the street, a more coherent, urban atmosphere.

Another advantage will be closer connections to Pentagon City. Mandle hopes that an improved Route 1 will “better unify the Crystal City and Pentagon City neighborhoods into a singular downtown area.”

Two intersections will be centerpieces of any attempt to change Route 1. First, in the north, the elevated crossing of 15th Street S. defines an automobile-oriented connection between Crystal City and Pentagon City. The Sector Plan calls for the overpass to be demolished and for the streets to intersect directly.

According to Schnaufer, this project could soon be taken up by VDOT as part of the agreement between Amazon and the commonwealth of Virginia, although specifics are still unclear.

Second, in the south, Route 1 meets the Airport Access Road. As it stands, the intersection is all but impossible to cross on foot.

The crown jewel of the Sector Plan is a proposal to convert that intersection and its looming overpass into a beautiful, green circle with Route 1 through traffic diverted into an underpass — just like, for example, Dupont Circle in DC. This proposal, dubbed ‘National Circle’, has never left the drawing board, and there does not seem to have been any new planning or design work done since the Sector Plan was published.

Crystal City in the 21st Century

Amazon chose Crystal City for HQ2 in large part because of the transportation that’s already there. Between 2001 and 2014, because of federal employment changes, Crystal City lost about as many jobs as Amazon will bring, leaving the area with empty Metro seats and a surfeit of parking. “As a result,” says the county, “there is tremendous capacity on existing transit services to carry many more people than we do today.”

Furthermore, Amazon itself is prepared to implement ‘transportation demand management‘ strategies, like transit commuter benefits. These strategies, in which Arlington is considered a national leader, help reduce the car commuting that clogs our streets with vehicles and our air with exhaust.

For Schnaufer, of Arlington County Transportation, this is a story about Arlington as a whole just as much as it is about Crystal City.

“Arlington County is known as a leader, in Virginia and across the country, for how we design transportation infrastructure projects,” he said. “Both the quality of our existing street infrastructure and the County’s plans for future improvements help attract companies like Amazon to Arlington.”

Mandle agrees, saying that “Arlington’s commitment to both incremental and larger infrastructure projects, even prior to the Amazon deal, illustrates an awareness that these infrastructure improvements were critical to enhancing the area’s economic competitiveness and long-term growth.”

Ultimately, the Sector Plan’s goals for National Circle and its other high ambitions for a gradually-improving Crystal City will remain guideposts for the area long after Amazon’s arrival.