(Updated at 10:45 p.m.) About a year ago at this time, Arlington looked to be in serious trouble down in Richmond.

In mid-March 2018, county officials faced the decidedly unpleasant prospect that they’d come out on the losing end of a bruising legislative battle with two local golf and country clubs.

One of the county’s foremost foes in the General Assembly had engineered the passage of legislation to slash the clubs’ tax bills, potentially pulling more than a million dollars in annual tax revenue out of the county’s coffers.

Arlington had spent years tangling with the clubs, which count among their members local luminaries ranging from retired generals to former presidents, arguing over how to tax those properties. Yet the legislation from Del. Tim Hugo (R-40th District) would’ve bypassed the local dispute entirely, and it was headed to Gov. Ralph Northam’s desk.

That meant that Arlington’s only hope of stopping the bill was convincing the governor to strike it down with his veto pen.

In those days, long before evidence of Northam’s racist medical school yearbook photos had surfaced, the Democrat was well-liked in the county. He’d raised plenty of cash from Arlingtonians in his successful campaign just a year before, and had won endorsements in his primary contest from many of the county’s elected officials.

Yet the situation still looked dire enough that the County Board felt compelled to take more drastic steps to win Northam to their side. The county shelled out $22,500 to hire a well-connected lobbying firm for just a few weeks, embarking on a frenetic campaign to pressure the governor and state lawmakers and launch a media blitz to broadcast the county’s position in both local and national outlets.

“It became apparent to all of us that every Arlingtonian had something at stake here,” then-County Board Chair Katie Cristol told ARLnow. “At a time when we were making excruciating decisions about our own budget, the idea that you would take more than million dollars and put it toward something that wasn’t a priority for anyone here was so frustrating.”

That push was ultimately successful — Northam vetoed the bill last April, and the county struck a deal with the clubs to end this fight a few weeks later.

An ARLnow investigation of the events of those crucial weeks in spring 2018 sheds a bit more light on how the county won that veto, and how business is conducted down in the state capitol. This account is based both on interviews with many people close to the debate and a trove of emails and documents released via a public records request (and published now in the spirit of “National Sunshine Week,” a nationwide initiative designed to highlight the value of freedom of information laws).

Crucially, ARLnow’s research shows that the process was anything but smooth sailing for the county, as it pit Arlington directly against the club’s members. Many of them exercise plenty of political influence across the region and the state, and documents show they were able to lean heavily on Northam himself.

“One would expect a Democratic governor to be highly responsive to one of most Democratic jurisdictions in the state,” said Stephen Farnsworth, a professor of political science at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg. “But this was a matter of great concern to a bunch of very important people in Virginia, and that may well be the reason why additional efforts were necessary.”

And, looking forward, the bitter fight over the issue could well have big implications should similar legislation ever resurface in Richmond.

“Structurally, this bill could absolutely come back someday,” Cristol said. “And the idea that a bill that has such deleterious consequences for land use and taxation in jurisdictions across Virginia could come back and garner support because of an effective lobbying interest is very much a real threat.”

A risky precedent?

Hugo kicked off the fight over golf course taxes in the state capitol by filing his bill in fall 2017, but the dispute had been percolating long before then.

Both the Army Navy Country Club (located along I-395 just past Pentagon City) and the Washington Golf and Country Club (near Marymount University along N. Glebe Road) had been fighting with the county’s real estate assessor for years.

Arlington officials sought to value the clubs’ based on the “highest and best use” of the land: in this case, as space for residential or commercial properties. That meant the county assumed that each square foot of land was worth about $12 — the two clubs control more than 370 acres of land, combined.

The county reasoned that land is exceedingly valuable in the 26-square-mile locality, where officials have trouble finding sites for schools and other public facilities, and ought to be treated as such. Residential properties near each club have often been valued at many times that amount, for comparison.

That means Army Navy was generally assigned a value of well north of $100 million over the years, with an annual tax bill hovering around $1.5 million, county records show. Washington Golf ranged in value from $42 million to $60 million, with a tax bill of $838,000 for 2017.

The clubs argued those tax bills were wildly unfair compared to other Northern Virginia golf courses, some of which are valued at a much lower rate. They claimed the high tax bills were forcing them to raise membership rates, putting a strain on members — in Army Navy’s case, many are active duty military or veterans.

So Hugo filed legislation to slash the valuation rate to around $0.50 per square foot, reducing the clubs’ annual tax burden by roughly $1.5 million, combined. The clubs also filed suit against the county in December 2017, challenging their 2014 property assessments.

But it was the legislative push that unnerved county officials the most. Losing the court case would impact just two property assessments in isolation (albeit valuable ones) — seeing the legislation pass could’ve opened the door for other landowners to follow the same playbook, they feared.

“It would set a risky precedent where any property owner who does not agree with their assessment could run to Richmond for a legislative fix,” then-Board member John Vihstadt warned a state Senate committee in February 2018.

Smooth sailing for Hugo’s bill

Cristol says the Board took the prospect of Hugo’s bill passing “incredibly seriously” from the moment it was introduced. She remembers the entire Board frequently checking in with the county’s state legislative delegation, and other lawmakers representing Northern Virginia, to make the county’s position clear.

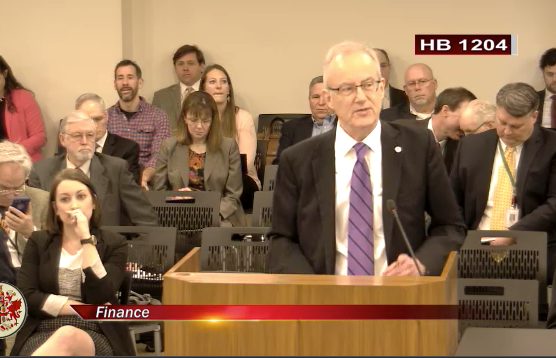

Del. Rip Sullivan (D-48th District), who represents parts of Arlington, spoke forcefully against the bill in a Feb. 7, 2018 committee hearing in the House of Delegates. At the time, Sullivan said he “probably spent more time on this bill than any other bill this session.”

“To my way of thinking, a resolution between the parties is always better than this body imposing an outcome,” Sullivan told his colleagues on the House finance committee. “I believe the parties are on course, pardon the pun, to a resolution of this.”

Sullivan cited “ongoing, good faith negotiations” between the clubs and the county, arguing that two sides were in the process of settling the valuation dispute and averting the need for any lawsuit.

At the time, however, Arlington had yet to offer a settlement of the lawsuit to the clubs, or hold extensive negotiations with them.

A timeline drafted by County Attorney Steve MacIsaac for use in later lobbying efforts notes that the county didn’t hold its first sit-down meeting with club officials until mid-March. The two sides discussed some inspections of the properties over the month of February, while the legislature was in session, but offered no terms to resolve the matter until later.

And Hugo argued that his legislation was the only reason any negotiations were happening at all.

“The ‘ongoing talks’ never really started until the bill was introduced,” Hugo told the finance committee.

Hugo’s colleagues saw things his way. The bill easily passed the committee with bipartisan support, passing both the Senate and the House with a mix of Republican and Democrat votes a few weeks later. The bill was sent to Northam by March 16.

Four days earlier, the County Board signed a $15,000 contract with Capital Results, a Richmond lobbying firm, documents and emails show. The firm’s past clients range from the National Rifle Association to Major League Baseball to Tesla Motors, according to state records.

Capital Results’ duties would include “message development,” “thought leader engagement,” and “media relations,” according to the contract. Partner Bea Gonzalez took point on the operation.

Cristol says the decision to hire the firm was partly out of desperation, as the Board recognized that heavily Democratic Arlington might have trouble winning sympathy from the Republican-dominated General Assembly without some extra help.

“We knew we’d need members of the majority caucus, which can be a little hard for Arlington,” Cristol said. “This was an opportunity for some outside help to reach some in the other party.”

Plus, the county had to face off against plenty of lobbying from the clubs themselves — Washington Golf employed two lobbyists for the legislative session, while Army Navy retained four of its own, state records show.

Gonzalez gets going

Emails show that, by March 14, 2018, Gonzalez had leapt into action.

She began coordinating closely with both Cristol and Pat Carroll, the county’s main government affairs staffer in Richmond, with one main opening goal: funneling a slew of letters opposing Hugo’s bill to Northam’s office.

Not only did Gonzalez help draft a resolution for the Board to pass condemning the bill, but she helped craft letters for all manner of Arlington politicians and community leaders about the country club legislation.

Sheriff Beth Arthur, Clerk of Circuit Court Paul Ferguson, County Treasurer Carla de la Pava, former Del. L. Karen Darner, the School Board, the heads of firefighter and police unions and local PTA presidents all communicated with Gonzalez about sending letters to Northam.

She drafted the letters and, in many cases, local leaders would send them onto the governor as their own, the emails show.

“At this point it is a numbers game [with] the number of letters and emails received,” Gonzalez wrote to Carroll on March 27.

Gonzalez also worked extensively with state Sen. Barbara Favola (D-31st District) to draft an op-ed and then place it in the Washington Post. It eventually ran on March 30, under the headline, “Virginia country clubs don’t need these tax breaks.” Gonzalez also helped Cristol draft her own op-ed on the matter, though it’s unclear if it was ever published.

Farnsworth said that, given the outsized influence of lobbyists around the capitol, it should hardly be a surprise that they may also be doing a little ghostwriting for politicians.

“Lobbyists draft bills, so why wouldn’t they draft op-eds?” he said. “Cynicism with respect to the authors of opinion columns or legislation is not generally misplaced.”

Earning some eyeballs

Earning media attention was another key part of Gonzalez’s strategy. The emails show she worked to secure Cristol interviews with TV and radio outlets alike and prep her for each one — she even worked with county staff to draft news releases on each stage of the legislation’s development.

And Gonzalez also endeavored to generate some more grassroots opposition to Hugo’s bill. While she reached out to a variety of different community activists, she found the most success with Annette Lang, who worked with the progressive group “We of Action Virginia.”

Lang and Cristol had chatted extensively about the golf course issue during the “March for Our Lives” gun safety demonstration in D.C., and Cristol forwarded her contact information to Gonzalez. From there, Gonzalez and Carroll provided her with talking points against Hugo’s bill and Lang whipped up support as part of a new group: “NoTaxSubsidies4Clubs.”

Lang and Cristol had chatted extensively about the golf course issue during the “March for Our Lives” gun safety demonstration in D.C., and Cristol forwarded her contact information to Gonzalez. From there, Gonzalez and Carroll provided her with talking points against Hugo’s bill and Lang whipped up support as part of a new group: “NoTaxSubsidies4Clubs.”

“It struck me that it’s really inappropriate for the General Assembly to step in on something like this, so I got kind of jazzed about it,” Lang told ARLnow. “Which is strange, because it’s a rather dry issue.”

Lang and her fellow activists began writing to state lawmakers about the issue, and sent letters to the editor along to local news outlets. They even took out ads blasting the bill in the Sun Gazette, including one pictured at left.

And when it came time for one of Northam’s regular appearances on WTOP’s “Ask the Governor” radio show, Gonzalez convinced Lang to call in, at Cristol’s urging. The hosts took her call during the March 28 broadcast.

“My question is, do you think real estate tax assessments should be established by local elected officials with disputes resolved in the courts, or should they be imposed upon by state legislators with disputes resolved by the state legislators that are not elected by the locality?” Lang asked.

Northam commended her for having a “good grasp of what we’re dealing with right now,” and vowed to “step in and take action” only if the county and the clubs couldn’t strike a deal.

Northam feels the heat

The governor’s tone during the radio show provided a good indication of how his staff was approaching the situation behind the scenes.

Emails show that Northam’s chief of staff, Clark Mercer, wrote to Cristol later on March 30 to get contact information for the clubs’ leaders. He said he planned to send an email “out to the group to encourage dialogue between the parties.”

But Northam’s appearance during the WTOP program also hinted at some of the pressure he was feeling to let the bill become law.

“Something I am sensitive to is a lot of these members are veterans,” Northam said. “A lot of them have protected our lives and have limited resources, and so the memberships have gotten fairly unreasonable, and that’s why this needs to be addressed.”

Emails between Gonzalez and Carroll indicate that the governor, himself an Army veteran and Virginia Military Institute graduate, was hearing the argument quite frequently that, without a slash in tax bills, the clubs would become unaffordable for their military members.

“[Former Arlington Del.] Bob Brink says that the governor is hearing from veterans,” Carroll wrote to Gonzalez on March 23. “Not sure yet how many.”

“Yes, veterans are calling in — and all of the VMI network too,” Gonzalez replied.

Cristol remembers being confused at hearing such arguments. “The idea that we would support veterans by giving tax breaks to country clubs, rather than investing tax dollars in services to support veterans felt bizarre to me,” she says now.

Nevertheless, it was clearly a powerful argument in the clubs’ favor. Hugo referenced the issue several times during committee debate; a March 3 op-ed on the conservative Virginia politics website Bearing Drift accused Arlington of “using an unfair application of tax policy to willfully run United States military veterans out of the county.”

Lang recalls several legislators telling her that they’d heard similar overtures. Del. Kaye Kory (D-38th District) told Lang in an email that “I am receiving voicemails from veterans urging me to support this bill and angrily demanding to know why I voted against it.”

“This misleading campaign is hypocritical and disappointing,” she wrote on March 25.

Some of the pressure from veterans was even directed Cristol’s way.

Someone tweeted at her on March 28 urging her to support Hugo’s bill based on what it would mean for veterans. She responded that “I’m honored to represent the >12k veterans living in Arlington County. I don’t think asking them to foot the bill for tax breaks for country clubs is a sign of respect.”

That tweet did not go unnoticed among the country clubs’ supporters. A few days after Cristol’s social media post, Carroll wrote to Gonzalez, saying she’d heard about the tweet directly from Suzette Denslow, Northam’s deputy chief of staff.

Denslow had gotten a call from Edward Mullen, one of the lobbyists representing Washington Golf, who was upset about that message. And Mullen is no stranger to the Northam administration — he served on the governor’s transition team, and personally donated $1,500 to Northam’s gubernatorial campaign.

Carroll wrote to Denslow to reassure her that the clubs and the county were working together and making progress on a settlement.

After the veto, a ‘good relationship’?

Regardless of any heat Northam might’ve been feeling, the governor came through on Arlington’s side by April 9, his deadline for acting on the bill.

He vetoed Hugo’s legislation, but delivered a warning in a statement attached to the decision: “I encourage the parties to continue negotiations to find a solution so that similar legislation will not be necessary in the future.”

This prompted rejoicing from the Arlington contingent, with one cautionary note.

“I spilled blood on this one,” Favola wrote to Gonzalez, Carroll and other county officials. “There is nothing left for a redo, so please reach a settlement with the clubs.”

Cristol followed up the next day with proposed strategies on how to sustain the governor’s veto, fearing that Hugo might try to muster the votes to override Northam’s decision. That would require a two-thirds majority in the House of Delegates, a heavy lift considering the bill didn’t originally pass with that much support.

Still, emails show Carroll and Gonzalez exchanged ideas about which local lawmakers might be well positioned to whip support for the veto.

Meanwhile, Gonzalez feared that Hugo was marshaling his own opposition to the veto as late as April 16.

“Been texting with Hugo, and he may be leaning on giving a long [floor] speech I think,” she wrote to Carroll. “So we need to be sure to be prepped.”

The county even agreed to extend its contract with Capital Results that same day. Gonzalez charged Arlington another $7,000, documents show.

“The veto being sustained was not at all something we took for granted,” Cristol said.

Ultimately, Gonzalez’s fears weren’t realized. On April 19, she wrote to a group of county officials that Hugo had decided not to contest the veto.

Six days later, the clubs and the county struck a deal to avert the lawsuit, according to an email from Army Navy’s chairman to his members.

The county agreed to reduce its valuation of the courses, and refund some of their past tax bills — the changes cut Army Navy’s tax bill by about $600,000 last year, while Washington Golf saved about $400,000. Word of the settlement made it to ARLnow by May 2.

Cristol says the ultimate outcome was undoubtedly the one the county had hoped for, but she added that there were certainly moments where county leaders felt “great frustration and disappointment” about the how the debate proceeded. Plainly, the whole saga left some hard feelings all around.

“[The clubs] chose, unfortunately, to take their case to Richmond and sue us at the same time,” Vihstadt told ARLnow. “Not the way to make friends and influence people, in my view.”

That’s not to say the experience left the clubs and the county entirely on bad terms, however.

“We are trying to maintain a good relationship with the county and hope to maintain that good relationship in the future,” Raighne Delaney, Army Navy’s secretary-treasurer, told ARLnow. Washington Golf’s representatives did not respond to a request for comment.

That being said, Cristol remains wary that the county could find itself doing battle with the clubs in Richmond once again, should that relationship deteriorate.

After all, she notes that Hugo — a Fairfax Republican who has frequently clashed with the county on all manner of issues — “is still in the General Assembly.”

“People in Clifton or other parts of the state could always decide they know better how to tax open space in Arlington,” Cristol said.

Main photo via Facebook