Arlington County is turning trash into treasure by growing thousands of pounds of fresh produce for a local food bank using compost from residents.

Last February, Arlington’s Solid Waste Bureau began a pilot program to create compost from residents’ food scraps. Now some of that compost is coming full circle and being used in some of the local gardens that supply fresh produce for Arlington Food Assistance Center (AFAC).

AFAC is a nonprofit that receives around a million and a half pounds of food donations annually. The goods comes from several sources: grocery stores, private food drives, farmers markets and farms, and gardens around the region, according to spokesman Jeremiah Huston. Part of that comes from its “Plot Against Hunger” program, which cultivates the fresh produce.

AFAC staffer Puwen Lee manages this program, which she helped grow back in 2007 after noticing the food bank distributed frozen vegetables even in the summer months.

“And I thought, ‘This is really strange because I got so many vegetables in my garden,'” she said. After mentioning it to the nonprofit’s leadership, Lee said the director dropped off 600 packs of seeds on her desk and left it up to her.

Since then, Lee, who grew up gardening in Michigan, estimates the program has received over 600,000 pounds of fresh produce and has grown to include gardens from the Arlington Central Library, schools, and senior centers — and now it’s experimenting with using waste from residents themselves.

Trading trash for treasure

The Solid Waste Bureau collects food waste in two green barrels behind a rosebush by its headquarters in the Trades Center in Shirlington. The waste is then dumped into a 10-foot-high, 31-foot-long earth flow composting stem that cooks the materials under a glass roof and generates 33 cubic yards of compost in about two weeks.

When Solid Waste Bureau Chief Erik Grabowsky opens the doors to the machine, the heady smell of wine wafts out, revealing a giant auger slowly whirring through the blackened bed, turning the composting food.

Grabowsky said the final mix is cut with wood chips — something not always ideal for most vegetable gardens. But Grabowksy says it’s an “evolving” mixture that the department will tweak over time and which he plans to test in the department’s own garden next to the machine.

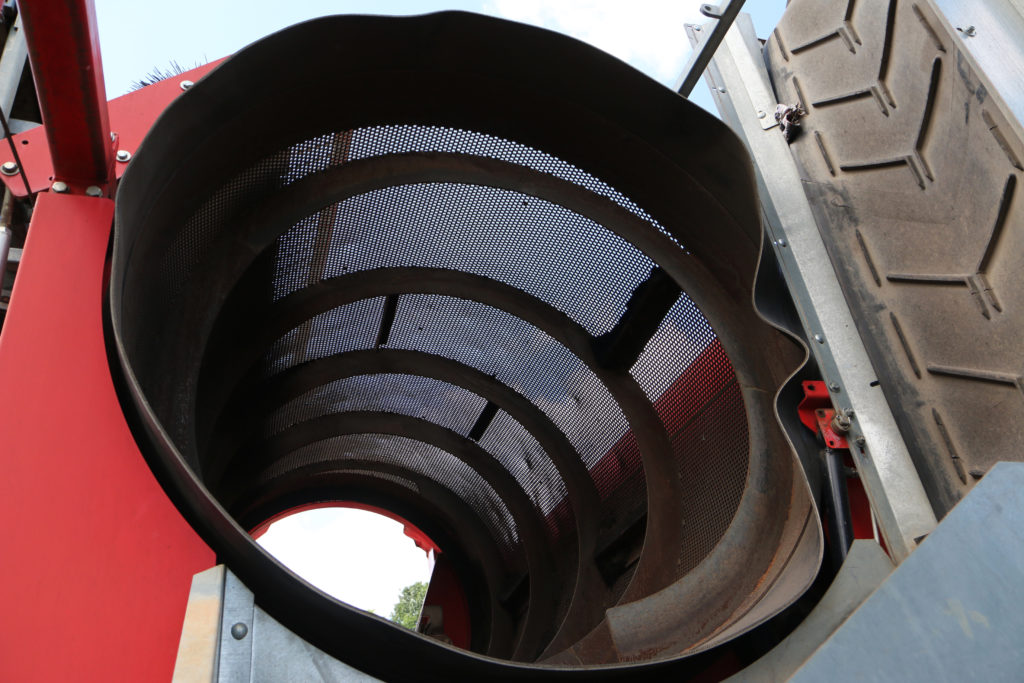

After the wood chips, the mix is shifted through a hulking “trammel screen” and distributed to AFAC and the Department of Parks and Recreation.

On a recent weekday, workers Travis Haddock and Lee Carrig were busy in Bobcats shuffling dirt off the paved plaza Grabowksy says will host the department’s first open house next Saturday, June 8 to show how the recycling system works. Normally, they manage repairs to the auger and the flow of compost in and out of the machine.

(When asked what their favorite part of the job was, they joked it was when the auger “stops in the middle and you got to climb in there.”)

The department’s free June event, called “Rock-and-Recycle,” will run from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. at the department’s lot in the Trades Center and will feature music and food trucks. Attendees will also be able to check out the compost for themselves, as well as the nearby Rock Crusher and Tub Grinder.

From farm to food bank

AFAC is currently experimenting with using the compost for one of its gardens. The nonprofit also makes its own mix using plant scraps and weeds pulled up from the beds.

Near AFAC’s Shirlington headquarters, volunteers run a garden that donates all its yield to the food bank. Boy Scouts originally built the raised beds that now make up 550 square feet of gardening space, and grow lettuce, beets, spinach, green beans, kale, tomatoes, and radishes, on a plot near a water pump station along S. Walter Reed Drive.

Plot Against Hunger manager Lee said the space was originally planned as a “nomadic garden” in 2013, but thanks to the neighboring Fort Barnard Community and the Department of Water and Sewer, it became a permanent fixture on Walter Reed Drive.

Certified Master Gardener Catherine Connor has managed the organic garden for the last three years. She says she’s helped set up the rain barrels and irrigation system that waters the beds in addition to supervising the planting. Now the beds are thick with greens and bumblebees hum between the flowers of the spinach plants that have gone to seed.

“Last year, we had just an incredible growing season,” Lee said. “From the farmers markets alone we picked up something like 90,000 pounds [of food.]”

Connor told ARLnow the garden generated 1,200 pounds of produce last year for the nearby food bank and she thinks this year’s yield will dwarf that thanks to some winter gardening. By last April, the garden had generated 16 pounds of food, she said. By this April they’ve donated over 200 pounds.

“We live in a really wealthy community.” she said. “And to me it’s appalling that we have as many people in poverty as we do.”

Lining up around the corner

Once produce is collected from gardens and farms, it’s either bagged up on site or taken to AFAC’s Shirlington building where volunteers bag it. The bags are then sorted by type and stored on shelves or in a refrigerator where they’re ready for the low-income residents who arrive for their once-a-week pick-up.

Residents can also pick-up bread and canned goods, which are sometimes donated via events like the ART bus’ recent “Canstruction” in Ballston. The Arlington Chorale dropped off 138 pounds of non-perishable donations while this reporter visited.

All told, AFAC serves food to a total of 2,400 people per week at 18 different distribution sites scattered around the county, AFAC spokesman Huston said.

“When I started a dozen years ago, we were serving 450 families every week and now we’re serving 2,400 every week. So the need is there,” said Lee, during an interview earlier this month. “And I think with the recession, with government shutdowns, with new SNAP [Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program] rules, it always affects people.”

AFAC’s service expansion mirrors the county’s struggle to carve out ways for people on lower-incomes to live in Arlington. The County Board has authorized homeowners to build backyard cottages and unveiled new initiatives to help add more affordable units back on the market, but staff recently admitted that the county has lost 17,000 affordable housing units since 2005.

“Arlington is not getting cheaper,” Lee said. “There will always be a need.”