An Arlington County policy on how defense attorneys access the materials they need to prepare their cases has become a hot topic in the already heated commonwealth’s attorney race.

Since Parisa Dehghani-Tafti launched her campaign to unseat Theo Stamos in the June 11 Democratic primary, discussions over the county’s discovery policy have featured in a candidate debate, a public endorsement, and a public letter opposing Stamos.

A discovery policy dictates which case files a prosecutor is required to share with defense attorneys. Some attorneys say Arlington’s policy of asking attorneys to hand copy this information at the courthouse is so cumbersome that it makes it difficult for them to represent their clients.

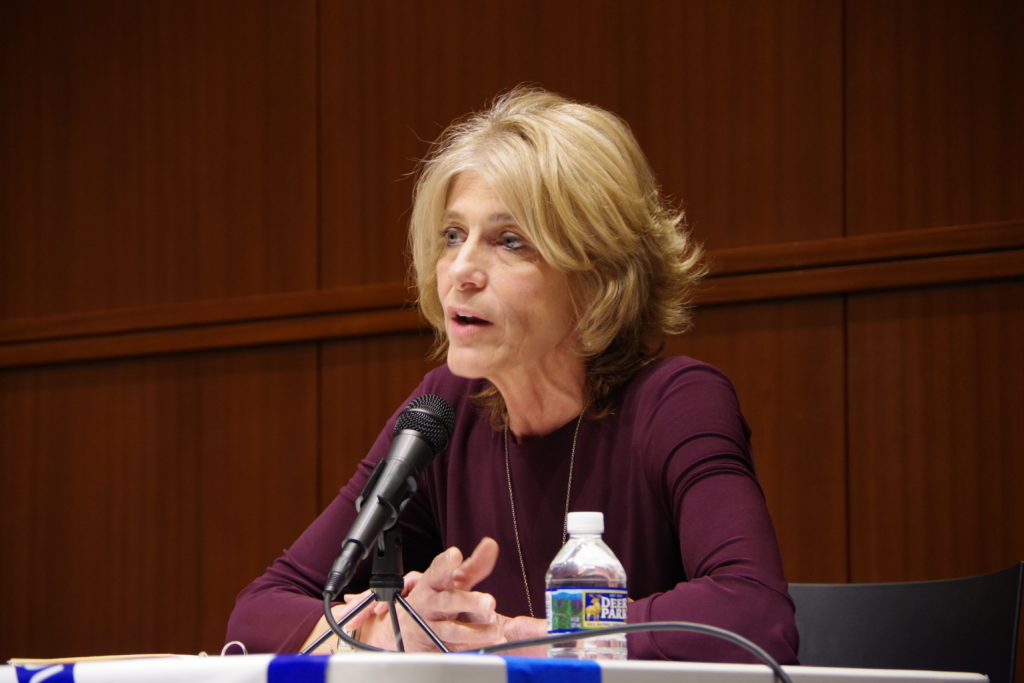

Stamos argued during an April debate with Tafti that the hand-copying policy protects witnesses’ privacy by preventing information like addresses, Social Security numbers, and dates of birth from leaving her office. She said her office would need additional resources to make the redactions necessary to share copies with defense attorneys.

In the meantime, defense attorneys have to sign agreements not to share their notes or dictations from misdemeanor or felony discovery files.

This contrasts to neighboring jurisdictions like Fairfax County and Alexandria, which regularly email copies of similar files to defense attorneys or provide take-home hard copies.

When asked if she had evidence showing increased incidents of witness intimidation in neighboring jurisdictions as a result of the more permissive discovery policy, Stamos told ARLnow the other jurisdictions might not have to “worry about the witness intimidation piece because they have an efficient redaction process.” She hopes to implement the same process in Arlington.

Four defense attorneys who spoke with ARLnow disagreed that the current policy was necessary, calling Arlington’s unique process for accessing case files “onerous,” “cumbersome,” and “horribly inefficient.”

Resisting Reform or Protecting Privacy?

“I’m looking at the police report in a paper format. And whether I’m typing it on my laptop or handwriting notes, I am literally just copying word for word what it says,” said defense attorney Elizabeth Tuomey, who has worked in the county for the past 15 years. She called the discovery policy “a complete waste of time.”

Tuomey, who is one of the signatories of the letter opposing Stamos, told ARLnow that the prosecutor’s office also does not allow defense attorneys to make copies of photos in discovery files. As a result, Tuomey says she has to describe the images in her notes and write down the file name if she wants to ask prosecutors to show an image during trial.

Defense attorney Terry Adams said he dictates descriptions of photos and sometimes has to draw sketches of important ones. He was an Arlington deputy sheriff in 1987 before becoming a private attorney, and he has donated to Tafti’s campaign and signed the letter opposing Stamos.

“We intend to use the upcoming months if I’m re-elected, and I hope to be, to streamline the discovery process to make as much available as possible,” said Stamos, who added that her office provides discovery “well in excess” of the rules set by the Supreme Court of Virginia.

The state’s rules only require prosecutors share the criminal history of the accused and any statements that person may have given to police, but they do not require the commonwealth’s attorney’s to provide copies.

Since Stamos was elected in 2011, she has allowed defense attorneys to view additional information like police reports, photos, and videos for felony cases as well as misdemeanor cases as long as they come in the office, because she says she doesn’t have any easy way to redact sensitive information.

She also noted that defense attorneys can request copies of certain files and her staff may create them on a “case-by-case basis.”

It’s a point she made for several years, including in a 2017 letter denying a request from then-Chief Public Defender for Arlington County Matt Foley to broaden discovery further.

The Virginia Supreme Court recently decided prosecutors must also share witness lists and expert reports, and must allow defense teams to read police reports, but the court delayed implementation until at least 2020. Stamos said her office would like to take the rules a step further and share digital copies of discovery, but first they require better redaction software.

“We’re working with our IT person in my office, and our head paralegal, and the police department because they have a relatively new record-management system that can be quite cumbersome to deal with it,” the prosecutor said.

Several attorneys who spoke to ARLnow said not only is Arlington the only jurisdiction in the region to still require hand-copied discovery, the process is also fraught with delays.

Attorneys are sometimes forced to share the two discovery rooms, or work in the public lobby. Defense attorney Damon D. Colbert said this can put witness’ private information at risk.

“I don’t want to disclose to anyone anything about my client,” said Colbert, who is one of the signatories of the letter opposing Stamos. “If I am dictating a police report into a voice recorder, things that I believe are confidential could be heard by third parties.” Last year, he had to take refuge in a hallway closet used to store Christmas decorations to dictate in private.

“We’re all closeted together a little on top of each other but that’s the nature of the facility that we have,” said Stamos.

David Dischley, a private defense attorney who signed a February letter supporting Stamos and who donated to her campaign, called the county’s discovery process seamless.

“I’ve always timely gotten all the information I need for a case and have always had positive experiences getting needed information from the prosecutors,” he said.

While Dischley added he experienced “minor difficulties” pertaining to wait times, it was nothing that impacted his ability to get information. In addition, he said the transcription work has not affected his ability to prepare for a case.

“If I’m going to come into Arlington I want to be handsomely compensated”

Another reason lawyers say transcription is burdensome is because the county’s policy only allows one person to check out discovery files.

“We can’t even send in paralegals to look at them,” said defense lawyer Philip Niemann Rhodes, who’s worked Arlington cases for the last 30 years and retired from county cases last Friday.

“Only the attorney of record can sign out the file,” Rhodes said. This means only the attorney assigned to the case can check out the records, and must physically escort any support staff to the rooms.

Some attorneys say the policy’s logistical issues mean the cost of doing business in Arlington can outweigh the benefits of taking a case.

Tuomey was assigned a murder case by the court in 2016 that required over 100 hours to transcribe the many discovery files. The task was so big she had to stop taking any other court-appointed work during the trial and bring on another attorney to split the work — and split the $3,000 fee for the case.

The judge in her case ultimately approved $15,000 in additional compensation via a special pool of annual state funds.

“But by the time that the paperwork was submitted to be paid, there were no waiver funds left,” said Tuomey. She estimates her take-home pay for the case was around $1,250.

Colbert said he knows “a lot a good lawyers who will not come to Arlington” and instead refer cases to him. He no longer accepts court-appointed cases in Arlington because the fees are too low to cover the discovery work.

“If I’m going to come into Arlington I want to be handsomely compensated,” he said.

“What that means is there’s a smaller pool of attorneys willing to practice here,” said Adams, and that means the accused have less choice for representation.

Burning through Berhane’s Files

Can there ever be too many files to copy by hand? Arlington Office of the Public Defender thinks so, thanks to a 2-terabyte-sized discovery file for a case that’s dragged on for 2 1/2 years as they’ve requested digital copies of the files.

The case began after law enforcement raided Caffe Aficionado in October 2016 and charged owner Adiam Berhane of running a scheme to profit off cloned credit cards. Co-owner Clark Donat pleaded guilty a year later, but Berhane’s jury trial for 55 felony counts has dragged on ever since, amid disagreements over whether the discovery can be processed by hand.

“Supposing a pace of 7 minutes per page — which in counsel’s experience is quite rapid-copying 100,000 pages of discovery would require 11,667 billable hours, or 69.45 weeks of time (working around the clock) for a single attorney,” Chief Public Defender Bradley Haywood wrote in a July motion demanding Stamos’ office give attorneys a digital copy.

ACPD Detective John Bamford, who is in charge of the Berhane investigation, testified in March that his team seized between 25-30 electronic devices. All together, the devices generated hundreds of credit card receipts collected as evidence as well as 100,000 pages of financial records from several banks for the investigation and a 500-page-long police report.

Haywood told ARLnow today that his team has spent “well over 120 hours” to date copying discovery files for the Berhane case. He declined to comment further, saying that the case is ongoing.

Stamos declined to answer a request for comment, citing the fact that the case was ongoing.

Previously, Deputy Commonwealth’s Attorney Margaret Eastman said the public defender’s lack of progress transcribing the discovery indicated Haywood’s office had “fallen down on their responsibilities to effectively investigate the discovery in this case” and sought to remove public defenders from the case on those grounds.

Arguments between both the public defenders and the Commonwealth’s Attorney Office have grown so heated that both sides have (unsuccessfully) asked judges to remove the opposing team.

Adams, Colbert, and Tuomey also testified during the March hearing. When Eastman asked each attorney whether the discovery policy caused them to have “fallen down” on their legal duties as counsel, they each said no, but added they could better prepare for trials with improved access to information.

After the March hearing, the Commonwealth’s Attorney Office provided digital copies for some of the electronic devices. However, Stamos doesn’t expect the new redaction and digital sharing system to be implemented before the end of the year. Public defenders may have to hand copy the remaining information before the case’s next trial.

Deputy Public Defender Amy Stitzel wrote in an email today that in terms of overall discovery work: “The attorneys at our office will likely spend 1,300 hours or more this year simply typing, hand-writing, or dictating materials in the prosecutor’s file; nearly the hourly workload of one attorney for a year.”