Arlington County is considering a new program to divert people with mental illnesses into treatment instead of jail.

The proposed program would waive incarceration for people with mental illnesses who are convicted of non-violent misdemeanors if they agree to an intensive treatment program supervised by a judge. All the officials who spoke to ARLnow about the program supported it, but some weren’t aware the county was working on the program and said they had little opportunity to add input.

The Arlington County’s Department of Human Services is spearheading the program. A spokesman told ARLnow on June 27 that in response to “recent requests” it would host a public meeting on the so-called Behavioral Health Docket on Wednesday, July 17 at 3 p.m. The location of the meeting has yet to be determined.

“The aim is to divert eligible defendants with diagnosed mental health disorders into judicially supervised, community-based treatment, designed and implemented by a team of court staff and mental health professionals,” said DHS Assistant Director Kurt Larrick.

This new docket aims to accept defendants 18 or older who reside in Arlington and who are diagnosed with a serious mental illness, Larrick said. Additionally, only defendants who have been charged with misdemeanors, not felonies, would be eligible for the diversion program. Defendants would need to agree to work with a team of mental health professionals and program staff to enroll in the docket and agree to follow a treatment plan with some supervision.

“These programs are distinguished by several unique elements: a problem-solving focus; a team approach to decision-making; integration of social services; judicial supervision of the treatment process; direct interaction between defendants and the judge; community outreach; and a proactive role for the judge,” Larrick said.

Where Mental Illness and the Law Collide

Officials and advocates say they hope that the docket will help break the cycle of recidivism that some people with mental illnesses fall into.

“Arlington has a significant number of people with mental illnesses that intersect with the criminal justice system,” Deputy Public Defender Amy K. Stitzel told ARLnow. “Evidence-based mental health dockets not only treat instead of criminalizing behavior that is a result of mental illness, they increase treatment engagement, improve quality of life, reduce recidivism and save money.”

“We’re talking about people who are arrested for vagrancy and loitering and trespassing,” said Naomi Verdugo, who has been an activist for people in Arlington with mental illness for several years. “These are largely misdemeanors and stupid things, and it’s because they aren’t well. We would be better off putting services around them than paying to incarcerate people who are just going to reoffend.”

“It is clear that the local and regional jails in Virginia have a substantial number of persons with mental illness in their care, and that this care is costly to the localities and to the Commonwealth,” says a 2017 study of similar programs statewide.

The most recent data from Virginia jail surveys indicate that statewide 1 in 10 of the inmates counted was diagnosed with a serious mental illness, such as PTSD or schizophrenia, and about 20% of all inmates had some kind of mental illness.

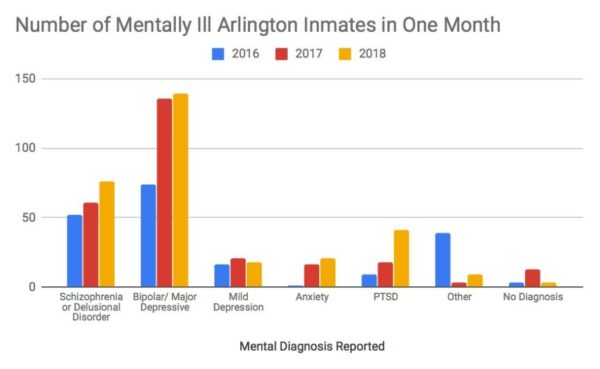

In Arlington, data from 2016, 2017, and 2018 indicates the most common diagnoses for inmates are bipolar disorder/major depressive and schizophrenia.

Chief Public Defender Brad Haywood said his office has been part of a team discussing mental health improvements for 15 years with the county’s Mental Health Criminal Justice Review Committee, and for the past five years with a subcommittee dedicated to creating a docket, called the Behavioral Health Docket Committee. Haywood strongly supports the idea of a Behavioral Health Docket but noted his office wasn’t notified the county had advanced plans for the docket until recently.

“This is not a transparent approach”

While he applauded DHS for moving the program forward, Haywood said he would have liked more input on the design when organizers decided to require defendants plead guilty before participating in the program.

“From our perspective, until early spring of 2019, the process for drafting and submitting an application for the Mental Health Docket seemed to be moving very slowly,” he said. “I don’t know what changed that took the process to where it is now, to having tight deadlines and short comment periods.”

Commonwealth’s Attorney candidate Parisa Dehghani-Tafti, who recently won the Democratic primary against incumbent prosecutor Theo Stamos, said she heard about the docket for the first time two weeks ago. During her campaign, Tafti advocated for a mental health court as part of larger criminal justice reforms, but said she wasn’t given a chance to comment on the Behavioral Health Docket.

She told ARLnow that she has concerns the new program “criminalizes mental illness” by requiring a plea to participate.

“It seemed to have been developed with little community input and limited consultation with agencies that will be responsible for administering the docket,” she said.

In June, a group of activists for people with mental illnesses sent a letter to DHS and the Arlington County Board over the lack of public input, writing “this is not a transparent approach.”

“This court will have such broad effects on our community,” the Arlington Mental Health and Disability Alliance wrote. “If changes are needed, we fear that the program will already be ‘baked in’ and we will have lost an opportunity to ensure that the docket is effective and evidence-based.”

Verdugo, who was one of the signatories of the letter, said she was “mystified” when a DHS staffer told her about plans for the docket recently. “I feel like we’ve been helpful to the county and it’s odd to me that they would develop this in a vacuum,” she said.

The activist group has since written a letter reiterating their displeasure at a lack of public input.

Their new letter also expressed concern that next week’s public meeting is scheduled during work hours and will be held in the Court House where the public is forbidden to bring phones. “Caregivers of those with disabilities often need to have their phones with them and turned on,” the group wrote.

The Community Services Board (CSB) includes DHS staff and Arlington residents. Board Chair Jeanette O’Keefe did not clarify whether resident members were briefed on the docket during the planning process.

“Speaking on behalf of the CSB Board, we are appreciative for the planning that has been done and look forward to the implementation of the Behavioral Health Docket and the improvement it will make in the lives of many persons who suffer from mental illness,” O’Keefe told ARLnow in an email, and noted that the county would host the July public meeting “in the interest of full transparency and to reach the maximum number of interested parties.”

Members of the CSB Mental Health subcommittee referred requests for comment to O’Keefe.

Larrick declined to share copies of the documents that outline the program, saying that DHS will share more information before the July 17 public meeting.

General District Court Chief Judge O’Brien will be in charge of the docket. The judge did not respond to requests for more information on the program.

The Future of the Docket

After the July 17 meeting, the county is planning to submit an application to the Office of the Executive Secretary of the Supreme Court of Virginia to create the docket. If the court approves the program, the county will have to monitor the docket and submit regular performance data to the court, which can act on the data to change the program.

“Once a Behavioral Health Docket is approved by the Office of the Executive Secretary, it is implicit that modifications may happen, incrementally over time, as the docket develops,” Larrick said. He added that the county would also use its own committees — the Community Services Board, the Mental Health Committee, and the Mental Health Criminal Justice Review Committee — to collect input on the docket.

The Commonwealth’s Attorney’s Office previously established a similar diversion program for substance abuse called a Drug Court. Lisa Tingle, senior assistant commonwealth’s attorney said the success of the new mental health diversion program will be “determined by the level of trust and transparency among the participating agencies.”

“If anyone around the table doesn’t share that goal, then they shouldn’t be at the table,” said Tingle.

Another hurdle for success may be funding. No outside funding is currently earmarked for the docket, according to Tingle, meaning each agency who works with the program will have to fund staff from its existing budget.

“For our office, that means a dedicated prosecutor that will have to fold these responsibilities into an existing caseload,” she said. “For the sheriff, that means allocating deputies to staff an additional courtroom. For the clerk, that means getting a clerk to sit with the judge for an additional docket.”

“Each organization is going to have to find a way to stretch resources to make this work,” Tingle added. “It is a big ask, but it is a worthwhile one.”

The Behavioral Health Docket comes on the heels of another program the county launched in April to encourage people addicted to drugs to turn in substances and waive charges in exchange for following a supervised treatment plan.

Ashley Hopko contributed to this report.