Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

“A nation may lose its liberties and be a century in finding it out.” -John Mercer Langston

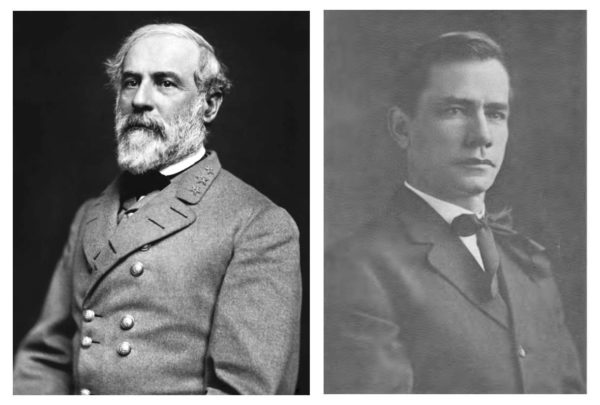

My county’s seal is a six-columned pediment, classical white on a blue field. This is the facade of Arlington House, built by enslaved Black people for George Washington’s step-grandson, the later home of Robert E. Lee, and the namesake of the county.

Arlington is changing. The seal is changing too, with an effort to replace the image of Lee’s mansion.

For us to make Arlington a county we can be proud of, we must understand how the racism in our past runs deeper than an image of a facade. For the new seal to be more than an empty symbol, we must use that understanding to build an antiracist future. To shape the change that is coming, we must know the legacy not only of Robert E. Lee but also of Frank Lyon and the men like him who, a hundred years ago, turned our county from hilly farms into the exclusive suburbs we know today.

This article is the first of a series. Over eight parts I will tell the story of Frank Lyon, the scars his racism left on our county, and how we can begin to heal those scars. These parts will be published biweekly, and as they’re published, you’ll also be able to read them with citations here. But this story is bigger than Lyon. This is in fact a story about the vast majority of neighborhoods across Arlington, indeed, across the United States — Frank Lyon only happens to illustrate it clearly.

In order to see the full picture, we first have to look at the decades after Lee departed and before Lyon arrived. We have to remember the decades when Arlington was Black.

At the dawn of the Civil War, Lee lost Arlington House. Although the county’s citizens voted to stay with the Union, secession carried Virginia, and the nation prepared for war. On the eve of war’s outbreak, Lee called for his wife, Mary Lee Custis, to leave their mansion and join him in Richmond. She ordered their one hundred and ninety-six enslaved people to pack the family silver and transport it to the Confederate capital. Mary Lee Custis stayed a few last days among the dogwoods, looking down at Washington in the late Virginia spring. Then she fled. Union soldiers took possession of the estate a few days later, toppling trees and erecting barricades in the elegant gardens to establish a fortified camp.

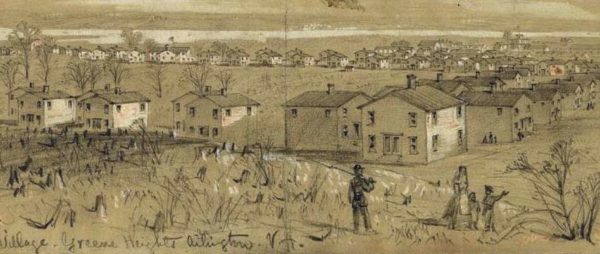

But as the war that ended slavery took its course, refugees began to appear in Washington. At least 16,000 Black people arrived in the city over the course of the war. They sought safety from violence and slavery. The fledgling capital didn’t have enough space for all these people, and the War Department established emergency camps for them. The officers of that department may have smiled at the justice when, in 1863, they turned over the grounds of Arlington House to establish one of the happiest of those new settlements. What had been home to Lee and the people he enslaved became a place for free Black families: Freedman’s Village.

More than a refugee camp, this was the first planned development in the county. The War Department set up the fundamentals for a decent life. They established schools, including vocational schools; they built a hospital; and they offered honest jobs for honest pay. But the heart of the village was the houses:

One-hundred white-washed, one-and-a-half story duplexes were constructed along a quarter-mile long thoroughfare through the Village. The clapboard houses used a pared-down version of the Classical Revival style… Classical Revivalism used symmetry and columns to allude to Greek temples, symbolically connecting America to the ancient democracy and its ideals through architectural style. In its vernacular execution at Freedman’s Village, the Classical Revival architecture used color and symmetry to convey the ideals of the movement. The external symmetry of the home was meant to lead to social harmony and stability. The white color of the homes was meant to encourage cleanliness, godliness, and order. Initially chosen by the War Department, this housing type was embraced by black Arlingtonians. They took great care in the maintenance and upkeep of these homes. When building their own homes later residents often recreated this style.

The people moving into these white-washed duplexes found more than homes. They found a community of their own making. Over twenty years, they took everything the War Department offered and made it theirs. The children went to school, and so did the adults — demand was so great that the town had to open a night school, and literacy rates in Freedman’s Village nearly tripled in only twenty years. The freedpeople learned to be carpenters, tailors, and blacksmiths, trades which were off-limits to Black people in most of the rest of the South. Black people of all ages came to the town, bringing their families or creating family there. They maintained their houses with care and cleanliness. And the freedpeople created places where they could be together. The people themselves built churches, mutual-aid societies, and fraternal organizations. Some of these institutions, like Mt. Zion Baptist Church, survive to this day, a century and a half later.

But Mt. Zion Baptist Church is no longer located on the grounds of Arlington House. Mt. Zion Baptist Church is today located on 19th Street South in Green Valley. Freedman’s Village was erected at a time when white political power was weakened, in our county and across the South. But when Reconstruction ended, it ended in a backlash of white supremacy.

In two weeks I will tell you about that backlash. But on this Sunday, March 14, the county will stop accepting public submissions of concepts for Arlington’s new seal. I submit that we could choose no better icon for our county than one of the one-and-a-half story duplexes that were home to the people of Freedman’s Village.

D. Taylor Reich is a native of Arlington and a graduate of H-B Woodlawn. They work as a researcher in urban mobility analytics with the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, where their research has been covered by international publications including The Guardian, BBC, and China Daily. Previously, they were a Fulbright scholar in Amman, Jordan. Taylor has served on the Arlington Transportation Commission and the Plan Lee Highway Community Forum.