A new timeline from Arlington County tracks how local policy decisions in the 20th Century disadvantaged people of color, particularly Black residents.

The county has released two timelines, spanning 1930-45 and 1946-60, which recount how policies and projects — touching on housing, education, transportation, planning and infrastructure — segregated Arlington. It also chronicles how Black residents responded by investing in their communities, getting into local government, protesting and going to the courts.

“This timeline will allow us to take inventory of who we are, where we have been, and how we are growing and evolving as we normalize, organize and operationalize racial equity,” said Arlington’s Chief Race and Equity Officer Samia Byrd. “It will help ground us in facts, communicate the importance of why we lead with race in addressing systemic inequities as a government, and remind our community that racism is real and why it matters.”

Once complete, the historical resource will span from the early 1600s to present day. For now, here are some of the important events that the county included from 1930-45:

- 1930s: The Hall’s Hill “Segregation Wall,” separating the majority-white neighborhood of Woodlawn and the majority-Black neighborhood, goes up.

- 1931-32: Route 50 is built and the streetcars between Washington D.C. and Mount Vernon are shut down, cementing the county’s racial divides.

- 1932: Hoffman-Boston Junior High School opened and would later become a high school. Up until this point, Black students’ education ended after primary school.

- 1932: After switching from an appointed County Board to an elected one, Dr. Edward T. Morton, the county’s first Black physician, became one of the first Black Arlingtonians to run for office. (It took 55 years for a Black candidate to win a County Board election.)

- 1940s: Pentagon construction displaced 225 African-American families, or 810 people. They were relocated to two trailer camps near Columbia Pike and in Green Valley.

- 1943: Without public transit, and with lower rates of car ownership, Black residents founded Friendly Cab in Green Valley and Crown Cab in Hall’s Hill to connect their communities to the region.

While Arlington recently honored the story of four students who desegregated Stratford Junior High School in 1959, the road to desegregating schools, mired in lawsuits and bureaucracy, began more than a decade prior and continued after their first day.

From 1946-60, here are some significant moments related to the struggle for an equal, integrated Arlington:

- 1946: D.C. ruled that Arlington students attending D.C. schools would have to pay tuition. Many Black Arlingtonians sent their kids to D.C. schools because they had more resources than the county’s segregated public schools.

- 1947: Constance Carter sued the Arlington School Board because facilities at the all-Black Hoffman-Boston High School were unequal to those at the all-white Washington-Lee High School.

- 1950: A federal judge reversed the district court’s ruling in favor of the School Board. The county was forced to invest in segregated Black schools and Black teachers were given the same salary as white instructors.

- 1951: Fire Station 8, the all Black-volunteer fire station that served Black communities, received its first county-paid firefighter — 10 years after the other stations.

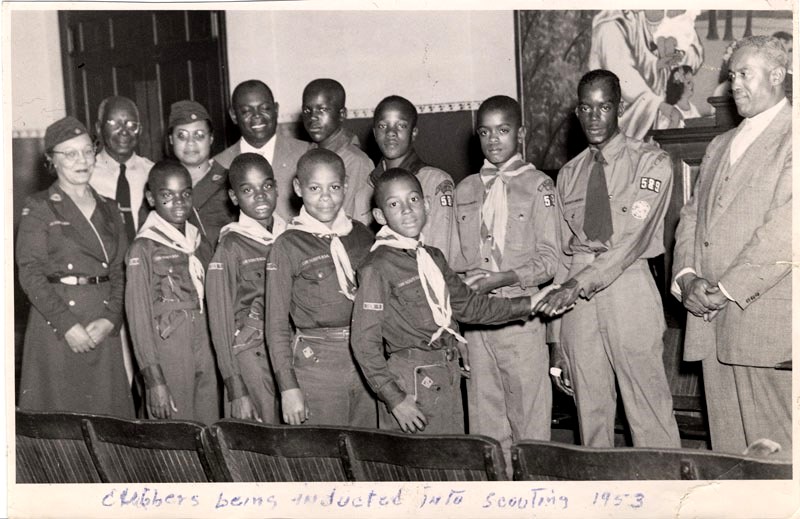

- 1953: The Veteran’s Memorial YMCA pool opened, serving “non-white” residents barred from other county facilities. The county opened its first integrated community center at Lubber Run Park in 1956.

- 1960: A sit-in at the People’s Drug Store in Cherrydale protesting segregated lunch counters kicked off a month of sit-ins. Woolworth’s store in Shirlington was the first to announce it was desegregating; 21 lunch counters followed suit.

The county will host a discussion next Wednesday (July 21) via Facebook Live at 7 p.m. called “Race Matters: Anticipating our Future, Examining our Past.”