A sociology professor at Marymount University and a former housing lawyer are poring over century-old property records to locate Arlington’s segregated neighborhoods.

It’s a time-consuming process, but the goal is to map Arlington’s “history of exclusion,” says professor Janine DeWitt.

“Our research is to take a look very closely at a granular level — lot by lot, parcel by parcel — and map the racially restrictive covenants that were in Arlington,” she said during a discussion hosted by the Arlington Historical Society last week. “We want to know the Arlington we’re in right now and how much of that was exclusionary.”

And DeWitt says she and her research partner, Kristin Neun, will not stop “until we find every last one of them and not before.”

This research effort is taking shape while the county grapples with its history of racist zoning policies through the Missing Middle Housing Study. Housing advocates who welcome the study, however, say it’s not enough to integrate neighborhoods that are still restricted as a result of the 20th-century practices DeWitt and Neun are researching.

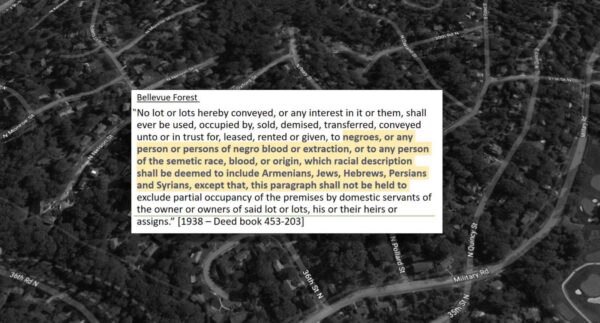

Until the Fair Housing Act of 1968 made racially restrictive covenants illegal and unenforceable, these clauses excluded potential buyers based on their race, ethnicity or religion. Such deeds governed Arlington’s housing market and mostly targeted Black Arlingtonians, while others included Middle Eastern immigrants, Jewish people and Armenians.

These covenants, codified by developers in conjunction with county government, applied to all future property transfers unless a property owner removed them. Only a handful did so after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled these covenants were unconstitutional in 1948.

DeWitt says she and Neun would have started their research at the Arlington County courthouse, leafing through physical pre-1951 property records, but due to Covid they conducted research every way they could until the county wrapped up a two-year project to digitize land records documents.

Even with the digital copies, the records still need to be read and searched by hand.

“Property records are tremendously inconsistent,” DeWitt said. “It’s incredibly difficult to parse this. It requires a high-touch approach.”

Once she and Neun find a deed with a restrictive clause, they match it with a current address and plug it into a map.

So far, they have mapped out covenants on properties in the Arlington Forest and Bellevue Forest neighborhoods. They found covenants for the historic subdivisions of Country Club View, Flower Gardens, Jackson Terrace and Woodlawn Village, which are now part of the Donaldson Run, Penrose, Tara-Leeway Heights and Waycroft-Woodlawn neighborhoods, respectively.

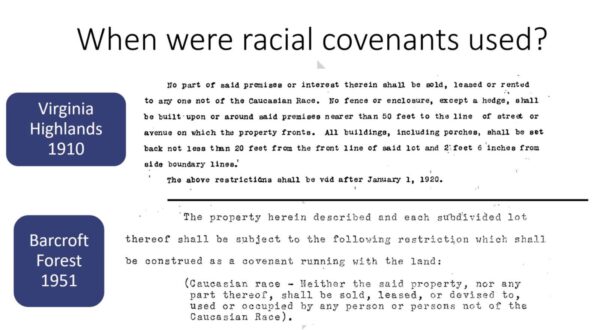

So far, DeWitt and Neun have observed these restrictions date from 1910 — and possibly earlier — all the way until the mid-1950s.

And some deeds were euphemistic, prohibiting occupancy “except for the race for which it is intended,” or prohibiting stables, pig pens, temporary dwellings and high fences.

“It’s amazing how you can vary restricting somebody,” said Neun, a former housing lawyer turned community educator.

Racial exclusion in Arlington tracks with regulations at the state and federal level, Neun said.

When Democrats took control of Virginia state politics in the early 1900s, they championed “homogeneity” — the idea that “homogeneous populations do better, live better, are happier and less risky,” Neun said.

As racially restrictive covenants took off in the early 1900s, state lawmakers passed laws to enforce them and the U.S. Supreme Court initially upheld them in 1926.

As racially restrictive covenants took off in the early 1900s, state lawmakers passed laws to enforce them and the U.S. Supreme Court initially upheld them in 1926.

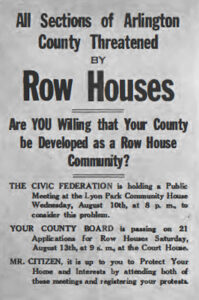

These covenants compounded on other land-use policies that established single-family homes as the chief form of housing in Arlington County while outlawing less expensive housing types, says Arlington County Chief Race and Equity Officer Samia Byrd.

For example, the County Board banned row houses in the 1930s, which were seen as a threat to the character of single-family homes. Thirty years later, the county added restrictions onto duplex developments, requiring duplex developers to get use permits, meet new lot-size requirements and design them like single-family homes.

During this time, Arlington saw a two-decade housing boom, as developers quickly built to meet the influx of people taking government jobs created by the New Deal and World War II. Arlington’s population tripled and became much whiter, while Black residents were displaced by these changes, including the construction of the Pentagon.

Byrd, a former county development planner, said restrictive covenants, zoning codes and the real estate valuation processes contribute to the low rates of homeownership today among people of color — as well as the concentration of communities of color in rental housing along Metro corridors, south of Arlington Blvd and in the historically Black neighborhoods of Green Valley and Halls Hill.

“It’s still based on that pattern and legacy laid out before,” she said.