The following in-depth local reporting was supported by the ARLnow Press Club. Join today to support local journalism and to get an early look at what we’re planning to cover each day.

Marguarite Gooden, who is now in her 70s, remembers the day that her grandfather, “a sage man,” as she describes him, told her something that would forever alter her family’s course.

“Keep the land,” he said.

When she could afford it, she purchased her first childhood home, which her father built on her grandfather’s property. She then purchased her second, larger childhood home, which her father built across what’s now named Langston Blvd, then Lee Highway, when his wife became pregnant with twins.

“I own both properties and I have had the wherewithal to make sure they’re in trusts, and that my kids and grandkids cannot sell them,” Gooden tells ARLnow.

Gooden, who shared her anecdote during a county-facilitated conversation on the Missing Middle housing study, said in an interview with ARLnow that she is glad she could help her kids stay in Arlington if they wanted. She said she wants teachers, firefighters and nurses at the nearby Virginia Hospital Center to be able to afford to live here, too.

But all around her, new construction in Halls Hill is increasingly unaffordable — a new six-bedroom, single-family home with a modern design recently went for $1.7 million compared to a circa-1995, three-bedroom townhouse went for $825,000. Another new construction, single-family detached home on a dead-end street is listed for sale for $1.9 million.

There are still some relative bargains to be had in the neighborhood, like the five-bedroom rambler that sold for $735,000, but with each “fixer-upper” sale comes with the chance that another huge house from a local builder will replace it.

The pricier homes came at the expense of this historically Black community, Gooden said, as neighbors moved away for more space or cheaper property taxes and sold the property they inherited from their parents and grandparents.

“That completely changed that neighborhood,” Gooden said. “We don’t even know all our neighbors anymore. I used to know everybody.”

After all this upheaval, could the county’s plan to allow two- to eight-unit buildings in single-family neighborhoods create more attainable homeownership opportunities in Halls Hill? Could it prevent future displacement?

It’s unclear.

One prevailing attitude is “something is better than nothing,” but concerns remain that Missing Middle will increase development in Halls Hill without bringing down the price. Certain streets already allow low-density multifamily units, and given the recent sale of two duplexes for $1.2 million apiece, they’re worried new “middle housing” won’t be attainable and won’t stem the tide of gentrification.

“People who live here are worried Halls Hill will be targeted, not more north in Arlington, where options are needed,” said community leader Wilma Jones.

Some developers, meanwhile, are excited to tap into buyers who want homes that feed into Yorktown High School and still have lower property values, at least to compared to other North Arlington neighborhoods.

“There’s such little supply, people want to be anywhere in North Arlington,” said Charles Taylor, the head of acquisitions for Arlington-based Classic Cottages. “It’s pretty schools driven. A lot of times, we don’t granularly pick and choose ‘We want to be in this block or that block,’ it’s like, ‘Hey, this is a lot in North Arlington, it feeds into Yorktown, let’s go there.'”

A changed neighborhood

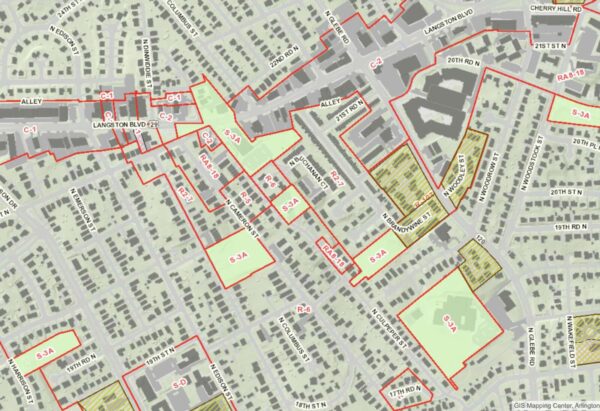

Also known as High View Park, Halls Hill, which straddles Langston Blvd between N. George Mason Drive and N. Glebe Road, is a historically Black neighborhood that was once separated from surrounding white neighborhoods by a wall. Residents built a thriving community, including the county’s first Black, all-volunteer fire department, and children — including Gooden — helped desegregate nearby all-white schools.

But the Black population dwindled in the 1980s and 1990s, as the original homeowners died and their descendants sold the properties and moved away.

“When grandma dies, and 12 to 13 people own a piece of the property, it’s hard to go up against a developer when some kids could buy out their other relatives,” she said.

When a property is divvied up this way, one descendant can buy out their relatives’ shares and sell the whole property. Or, one descendant sells his or her portion to a developer, who can then sue to forcibly remove the other descendants as shareholders and buy the property. (Developers used these partition sales to turn a Black enclave of landowners on a South Carolina island into the Hilton Head resort.)

Earlier in the 2000s, modest Halls Hill homes built in the 1920s-40s were replaced with ones that were increasingly unattainable for Arlington’s Black population, which has a median household income around $67,000, per the county. The county’s white population has a median income around $109,000.

“It’s only been two decades for my 100% Black neighborhood to become 20% of the neighborhood,” Gooden said.

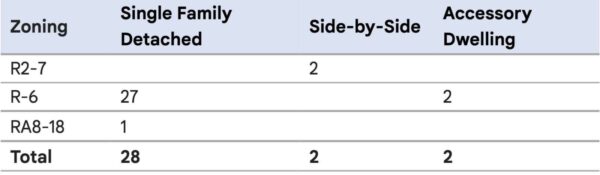

In the last four years, 30 new homes and two accessory dwellings have been constructed in the Halls Hill area, says Arlington Dept. of Community Planning Housing and Development spokeswoman Erika Moore.

Mostly, single-family homes were torn down and replaced with new single-family homes, two with accessory dwelling units. Three lots were split to make six homes and one house was built on an empty lot.

“We’re all for doing two-, three-, four-, six- and eight-unit buildings because right now, we’re only building houses in North Arlington that cost more than $2 million,” said Taylor, of Classic Cottages, during the panel. “And there are only so many people out there who can afford that.”

Andrew Moore, president of Arlington Designer Homes, tells ARLnow this pattern makes sense.

“In the last 20 years, you have been able to buy less costly homes in Halls Hill. And in the last 10 years, there’s been a lot of redevelopment there, just like all of Arlington. Maybe it saw more because it’s more cost effective than, say, Williamsburg,” he said.

The clip of 28 redevelopments in four years seems “absolutely normal,” he said, particularly for a neighborhood like Halls Hill, where the oldest houses still standing were built between 1920-1940, and have reached the end of their life cycle.

‘We’ve done our share’

Halls Hill has always been a patchwork of zoning districts: R-5, which allows one-family homes on smaller lots and architecturally compatible two-family homes; R-6, typical single-family home districts; R2-7, two-family homes and townhouses; and R8-18, apartment districts.

In short, parts of this neighborhood have the housing diversity that county leaders are thinking about allowing throughout Arlington. The county is considering amending the zoning code to allow two- to eight-unit buildings, depending on lot size, in neighborhoods that are currently zoned for single-family dwellings alone. That’s about 75% of Arlington’s residential land, according to the county.

Today, about 30% of existing housing could be classified as “middle housing,” but the county says these units are not evenly distributed.

Gooden agrees, saying segregation led Black Arlingtonians, who lived in a handful of neighborhoods, regardless of income level, to build middle housing “by necessity.”

“Historically, we had the school custodians live next to the prominent businessmen,” Gooden said. “That’s how we survived and that’s why I still live here.”

On N. Cameron Street, a newly renovated fiveplex sits next to a newly constructed four-bedroom single-family house, which replaced a house built in 1975. A 13-unit garden apartment building is next to a one-bedroom, one-bathroom house that Jones’ uncle built.

“I think we’ve done our fair share,” she said. “We’ve had open arms.”

Market conditions and Missing Middle

While the face of Halls Hill has changed in part because of the “anywhere in North Arlington” attitude Taylor described, residents say they hope Missing Middle could redirect some redevelopment to other desirable neighborhoods.

For instance, if developers could sell a quadplex to four families, the additional density could make it financially viable to build in pricier neighborhoods while delivering more attainable market-rate dwellings.

So it raised neighbors’ eyebrows when a “middle housing” option — a duplex that looks like someone held up to a mirror to one of the newer farmhouse-style single-family homes — went up on the 2000 block of N. Dinwiddie Street, replacing a three-bedroom, single-family detached home built in 1920. The units sold for $1.2 million each.

“I don’t think developers are going to spend the kind of money they’d have to spend to buy a piece of property to change it to a duplex that is affordable,” Gooden said. “That is my number one concern about Missing Middle. I don’t think it’ll be implemented equitably.”

The county maintains that the main goal of Missing Middle is not increasing “affordable housing,” but rather, providing a range of attainable options for people earning 80-100% of the area median income, or more than $102,480 for a family of three.

While the county invests in dedicated affordable housing for 30-80% AMI households, those closer to the average are at the whims of the housing market. Given zoning that prohibits anything but single-family homes in many neighborhoods while allowing much higher density along Metro corridors, the market is mostly producing either new rental apartment buildings or new detached homes well out of range for even families earning low six-figure incomes.

For Taylor, the math pencils out. To make a profit, a redeveloped single-family home on a $1 million lot would need to sell for $2 million, and two duplexes for $1 million each. Attaining deeper affordability would require four or more units.

“With four units, you’re doing four kitchens and four HVAC units, so roughly, costs per square foot might be higher, but your land costs get cut in four,” he said in an interview after a recent panel on Missing Middle at George Mason University.

Developers, he said during the panel, catch a lot of flack for building so-called McMansions. But his group is open to building other housing types if it’s profitable.

“Believe me, we have no great love for building only huge, single-family houses that are really expensive,” Taylor said during the panel. “That’s just what we have to do given what land costs in Arlington, and what you can do with land zoned for single family.”

(Although the county and supporters of Missing Middle, including the NAACP, cite racial equity as a reason for righting the wrongs of Arlington’s zoning laws, those on the panel — like a recent Arlington County Civic Federation panel on Missing Middle — were all white.)

Moore, of Arlington Designer Homes, says it’s hard to say whether flexible zoning will result in significant multifamily development in Halls Hill.

“The X factor is what is marketable,” he said.

Displacement and Black homeownership

Displacement was a central issue for Portland, Oregon at the time it approved zoning changes to allow middle housing, according to Sandra Wood, Principal Planner, City of Portland Bureau of Planning & Sustainability, who also participated in the George Mason panel.

In fact, four commissioners voted against the proposal over concerns that low-income renters would be displaced, Wood told ARLnow. Portland’s planners had done a displacement risk analysis to see what would happen, and it determined displacement would decrease by 28% if middle housing were allowed.

“If somebody’s renting a single-family house and the owner says, ‘I can put an eight-plex or six-plex there, now it’s worth it for me to sell it,’ then a family is being displaced,” she said. “But if eight units are being created, that family could potentially be in that unit later on.”

Renters are more at risk of displacement because they don’t control whether their house is sold or redeveloped, said Moore, Arlington’s planning division spokeswoman. For this reason, displacement risks are lower in the R-5 to R-20 zoning districts, where only 15% of households are renters, compared to 62% of households countywide.

“That does not mean that renters living in these zoning districts are less (or more) at risk from displacement than renters living in other zoning districts,” she said. “However, redevelopment that occurs in R-5 to R-20 zones is more likely to be the result of a homeowner who chooses to sell or rebuild because 85% of households living in these zoning districts own their homes.”

The NAACP has recommended the county assess forthcoming developments to gauge whether they could displace an existing community, and if so, require mitigation through tools such as property tax deferrals for lower-income homeowners and preferences for first-generation homebuyers.

For Jones and Gooden, even if the Missing Middle changes allow for a more inclusive neighborhood and come with safeguards, it’s likely coming too late for Halls Hill.

“It’s not the same,” Gooden said of the neighborhood as it used to be. “You looked out for each other. Culturally, we lost that.”