(Updated 11/02/22 at 9:20 a.m.) “Do you know how it feels to look at your daughter when she can’t move her eyes?”

That’s an Arlington mother, who spoke to ARLnow on the condition of anonymity, about a recent fentanyl overdose her 13-year-old daughter survived. It happened off school grounds, but the mother believes her daughter took the drugs during school hours.

Parents and school community leaders who have spoken with ARLnow say that students in middle and high school are able to access counterfeit prescription oxycodone laced with fentanyl at or near schools.

The mother who spoke to ARLnow said her daughter started vaping nicotine and marijuana in middle school, and by the end of eighth grade, got a hold of counterfeit Percocet — a mixture of oxycodone and acetaminophen — cut with fentanyl.

“The only thing I want is for the parents to know that kids can get every kind of drug inside the schools,” she said through a Spanish-language interpreter. “I want them to be conscious and aware of what’s going on in the school. I don’t want other parents to go through what I went through and I want the schools to pay more attention.”

It has been difficult to quantify drug use among Arlington students. Parents fear parent-shaming — but the mother who spoke with ARLnow did say three other moms she knows are struggling with the same problems — and ARLnow couldn’t get data specific to drug overdoses involving minors.

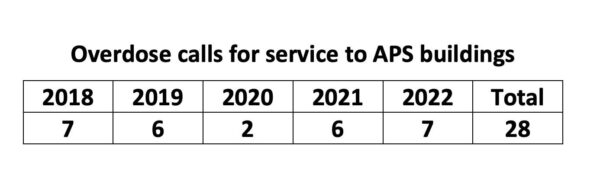

The Arlington County Police Department provided the number of calls for service to Arlington Public Schools buildings involving reports of an overdose, which encompasses use of prescription drugs, illegal substances or alcohol.

The data shows there has been a relatively small but steady number of calls to buildings since 2018. Although there was a brief drop when schools were closed during the early stages of the pandemic, the rate hasn’t changed despite the decision to remove School Resource Officers from school grounds.

“Overall, the volume of juvenile-involved opioid cases remains limited across Arlington, however, all cases involving opioids are taken seriously and thoroughly investigated,” ACPD spokeswoman Ashley Savage said.

Anecdotally, there were three overdoses last academic year, according to Elder Julio Basurto and Janeth Valenzuela, who founded Juntos en Justicia, an advocacy group representing Arlington’s Latino population. This school year, they have only heard of the overdose involving the 13-year-old girl mentioned earlier.

Basurto and Valenzuela noted that they have heard teens take the drugs in the bathrooms and distribute them in nearby parks and by vape shops near the schools.

“It’s getting out of hand,” Valenzuela said. “If we don’t do anything to correct this we’ll lose a generation.”

https://twitter.com/ElderBasurto/status/1583435692331257856

What’s going on

Basurto said he has heard different descriptions of what kids are taking, and that ambiguity is part of the problem.

“We can’t confirm exactly what it is,” he said. “Something they smoke, something square in their mouth, they get high off that.”

He described some students obtaining blue pills that are then crushed into aluminum foil. Those are counterfeit oxycodone pills, known as “blues” or “M30s.”

“The real concern, the real worry, is these counterfeit pressed pills,” says Jim Dooley, who has taught more than 900 Arlingtonians how to administer Narcan through the Arlington Addiction Recovery Initiative. “What kids are getting — and adults — in a large number of cases, are pills that look identical to commercially manufactured pills: Adderall for attention, Xanax for anxiety.”

And illicit distributors are increasingly cutting these pills with fentanyl, which is 50 to 100 times more powerful than heroin, to create a cheaper, more addictive drug, according to the Drug Enforcement Agency. People overdose easily because tiny amounts can be lethal, and many drug users are unaware their drugs are mixed with fentanyl. Synthetic opioids such as fentanyl were responsible for about 66% of the fatal drug overdoses in 2021, per the DEA.

Dealers are also reaching young people through social media. The DEA says 129 investigations this year are linked to social media platforms, including Snapchat, Facebook Messenger, Instagram and TikTok.

Because one would need a fentanyl test strip to determine if a drug is laced with it, Dooley teaches people, regardless of age, only to consume medicine that a doctor prescribed and a pharmacy fulfilled. But the pervasiveness of over-the-counter and prescription drugs is the reason counterfeit pills can proliferate undetected.

“Think how easy it would be to bum a Motrin because your period is giving you bad cramps,” he said. “It’s not hard to conceal these things. They don’t look like something that needs to be concealed.”

And an overdose isn’t particularly cinematic, either, Dooley explains. People appear to be nodding off — they almost look peaceful — because opioids attach themselves to nerve receptors and prevent signals to the brain to breathe.

“People look calm but they’re not,” he said. “They’re dying.”

Narcan knocks opioids off these receptors and there is no way to abuse Narcan, Dooley said.

“Local public libraries have Narcan next to automated external defibrillators,” he said. “That’s wonderful. There’s no reason that shouldn’t be the case in all other types of buildings.”

What schools and police are doing

APS spokesman Frank Bellavia acknowledged issue of drug abuse in Arlington and said the school system is taking the issue seriously.

“APS takes the health and safety of its students very seriously, to include any reports of the selling or distribution of drugs and other substances on school grounds,” he said. “Students, staff, and families are always encouraged to inform school administration if they have information that leads them to believe this is occurring.”

Six substance abuse counselors work in APS secondary schools and programs, providing regular education to students in classrooms about current trends, research and statistics on drug use, and provide resources and services to students and families, he said. They are also training some staff, including elementary teachers, in how to use Narcan.

“Classroom lessons are delivered in all middle and high schools, as well as our 5th graders,” Bellavia said. “This year, we are also focusing on getting into the 4th grade classrooms. This education talks about unused prescription drugs used in the homes, teaching students what dangers to look for and what to avoid touching.”

School staff and school safety coordinators patrol the buildings.

“Staff, SSCs and SACs are monitoring halls throughout the day,” he said. “At the secondary level, there are at least four school security coordinators in each school. School staff have been trained and reminded about the importance of doors remaining closed and for all visitors to be directed to the main office. School administrators and other staff also regularly monitor hallways and doorways in schools.”

When asked about the number of student overdoses on school grounds in recent years, Bellavia referred ARLnow to the police. As for the rumors that drug use happens in the bathrooms, Bellavia said APS “wouldn’t necessarily know” how an overdose occurred unless there was a follow-up police investigation or the family told staff what happened.

Bellavia stressed that drug use among students is playing out across the country and solving the problem is not just the school system’s responsibility.

“It needs to be a partnership between the schools, county, families and law enforcement,” he said.

Savage says ACPD is a member of the Arlington Addiction Recovery Initiative and “is committed to working collaboratively with county agencies and stakeholders to reduce the incidents of substance use, dependency, and overdose in our community.” She listed a number of the department’s efforts:

- Connecting overdose victims to the Department of Human Services for follow-up. This referral system has led to an increase in the number of individuals seeking treatment through County programs.

- Establishing four permanent drug-take back boxes across the County, collecting just under 10,000 lbs of unwanted, unused and expired prescription medications since implementation in June 2018.

- Training officers on how to respond to an opioid overdose using the reversal medication Narcan. Officers have deployed Narcan 20 times in 2022.

- Participating in town hall discussions and other educational opportunities to raise community awareness about the dangers of substance use.

- Sharing public messaging when potentially deadly batches of narcotics circulate in the region so those who may be affected by addiction can take the necessary steps to protect themselves and others by utilizing available resources.

- Thoroughly investigating narcotics incidents to identify those that distribute dangerous controlled substances within our community. These efforts have led to several significant arrests and convictions over the last several years.

Savage said that community members can anonymously report information related to narcotics distribution and activity using ACPD’s online confidential drug activity tip site.

A disconnect in services and help

Despite efforts from ACPD and APS, it seems families can fall through the cracks and kids can keep up their drug use.

The mother who spoke to ARLnow said she talked to school principals, tried to schedule a meeting with Superintendent Francisco Durán and got put on the county’s waitlist for psychiatric care. She described being frustrated at every turn when she sought help for her daughter, who showed obvious signs of getting high while at school — becoming verbally and then physically aggressive and overly sleepy.

“How is it possible that kids are able to continue in class when they’re under the influence? Why aren’t [school staff] reporting it? Why aren’t they letting [parents] know?” she asked

Over the summer break, she put her daughter in an intensive outpatient program in Alexandria. Her daughter improved, but things worsened once school started — confirming, the mother said, that she is getting the drugs through her connections at school.

While APS cannot comment on individual cases, Bellavia said counselors have their work cut out for them, given issues such as bed shortages in treatment facilities.

“Reports from professionals [suggest] that it really challenging right now,” he said. “For example, the substance abuse counselors can support discussions with families about whether long-term treatment is needed, but whether or not they can receive it is extremely challenging based upon available beds, limited right now due to needs, insurance — Do they have it? Will it cover it? It may only be covered for 5-10 days, only specific programs like detox versus treatment.”

APS and the county run a three-session, referral-based restorative program aimed at helping students found with illegal substances get back on track. But it’s not therapy for students deep in the throes of addiction.

“Second Chance is a restorative justice education program for Arlington middle and high school students, helping them avoid alcohol, drugs, and certain other substances,” he said. “Second Chance is not treatment or therapy. Students showing signs of early substance use will benefit most from attending Second Chance.”

When asked about the program, the mother told ARLnow that kind of intervention would be too little, too late for her daughter. She’s fighting to get her into a therapeutic group home.