(Updated at 7:30 p.m.) Braylon Meade’s classmates would know he was already seated by whether his basketball shoes were outside the door.

“He’d get up at 5 a.m. and after a workout, go to class at 7:30. Everyone said he would smell horrible. He would leave his shoes outside the classroom because he smelled so bad,” his teammate, James McIntyre, said with a laugh.

Shoes aside, his hustle garnered the admiration of his teammates, who agreed to him being their leader, overseeing drills and shouting out encouragement and direction during games.

“All the kids respected him because of how much work he put in… he worked so hard this summer to compete and play this season’s games,” W-L Head Coach Robert Dobson said. “He became our glue.”

McIntyre, who has known Meade since the third grade, says he was energetic but quick to share the ball. While not the tallest team member, he always ran to guard the opposing team’s best player.

“He went above and beyond to make himself the best athlete that he could be,” said Mark Weiser, a W-L parent who coached Meade in travel basketball. “He was the kind of player that, if you asked him to run through a brick wall, he’d do it and not complain.”

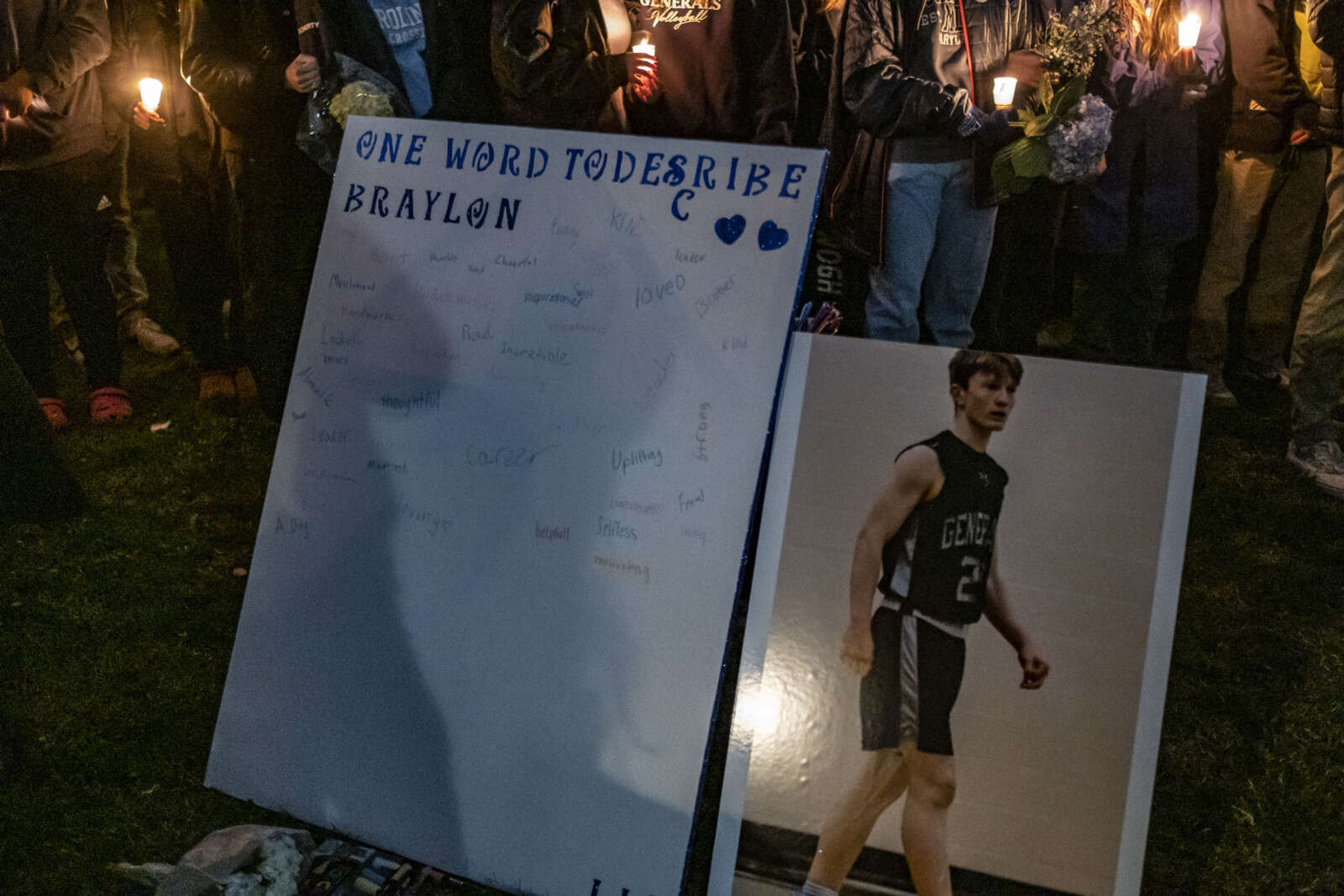

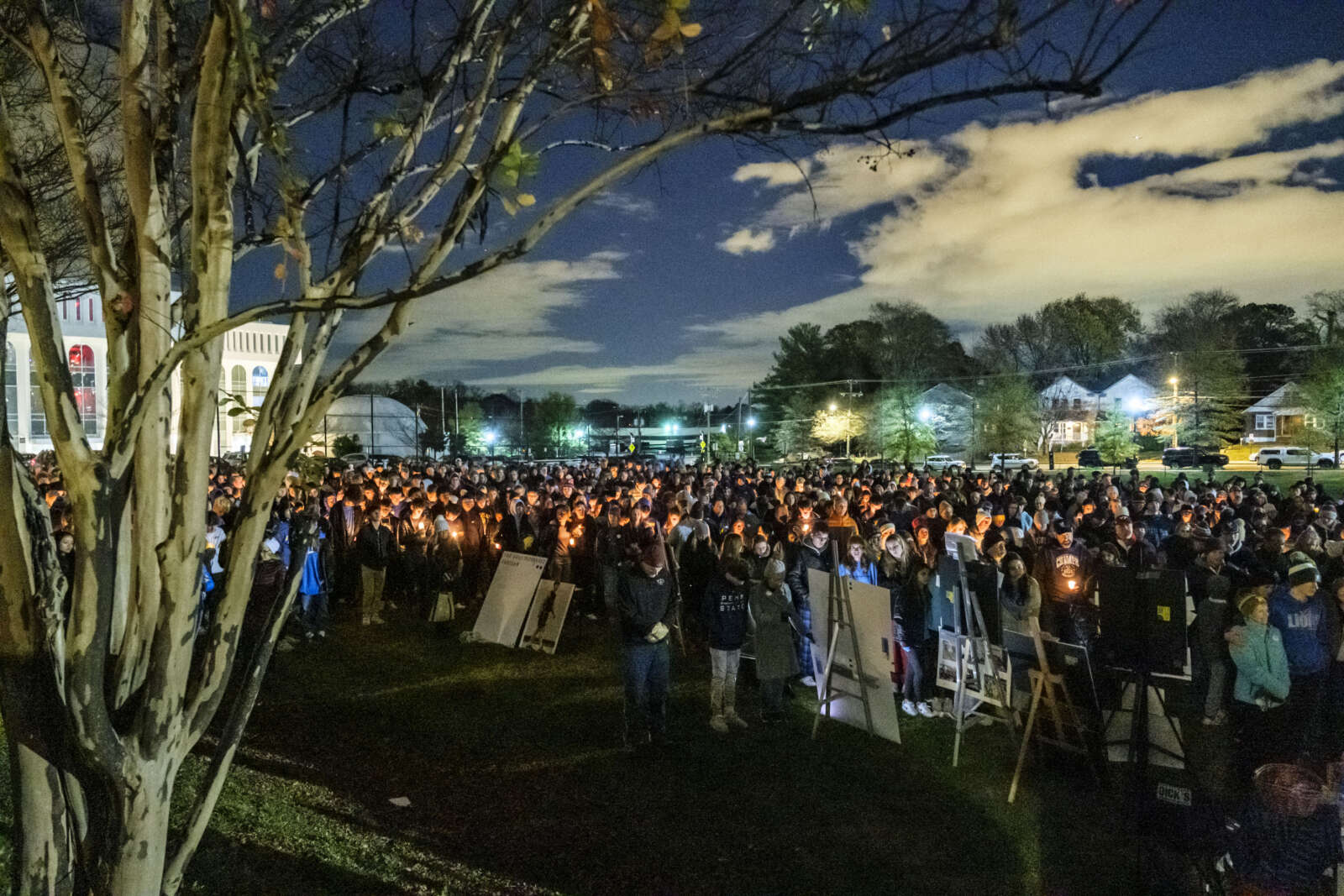

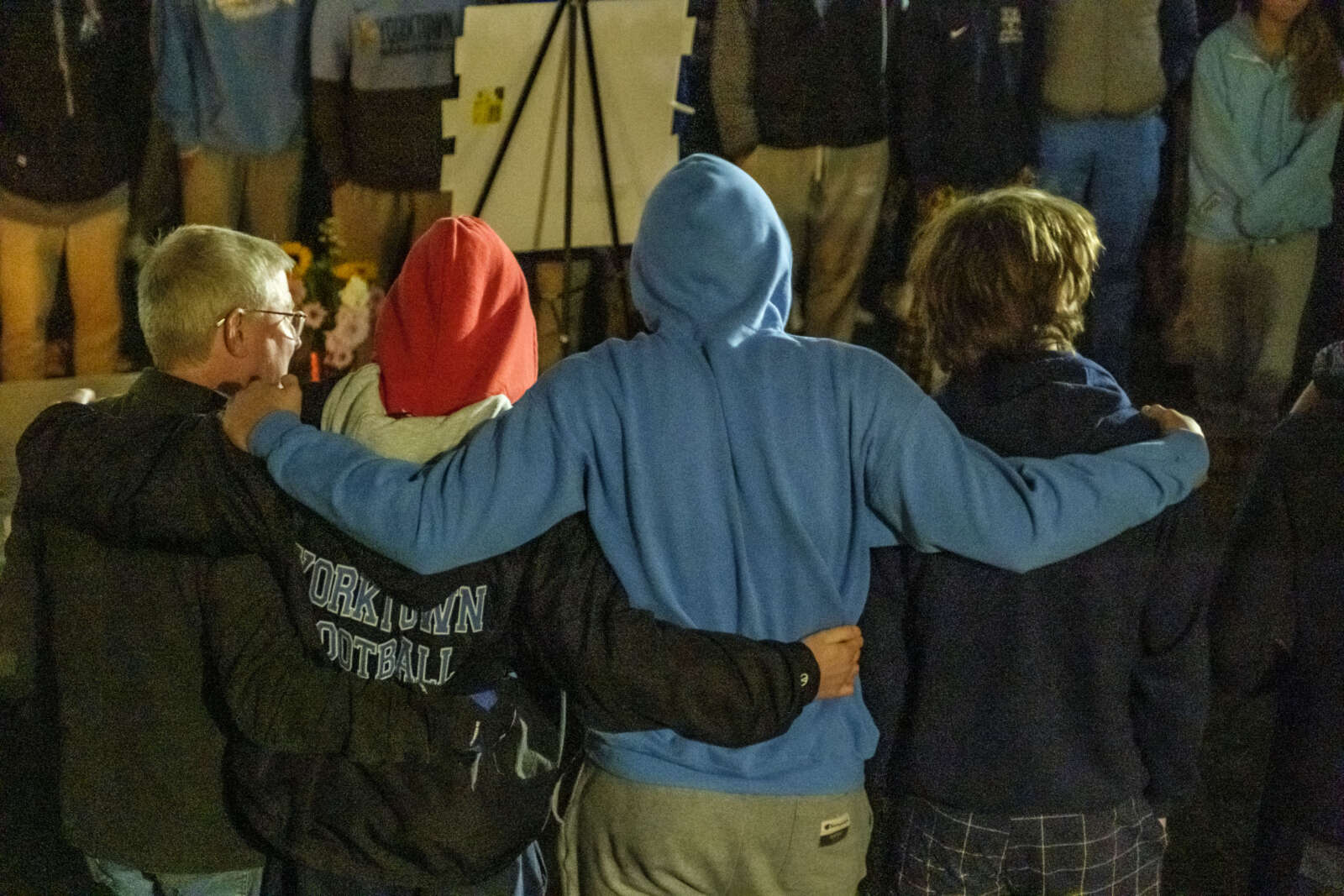

Meade died just before the start of the season this week and before he could show players across the region and state all the work he put in over the summer and fall. The 17-year-old was killed early Friday morning in a car crash, and a teen driver involved in the crash was charged with a DUI and involuntary manslaughter. On Sunday, hundreds of people turned out at the high school for a candlelight vigil organized in his memory.

In the wake of his death, family and community members are finding ways to honor his legacy. This morning (Wednesday), a scholarship fund in his name for Arlington Public Schools alumni went live on the Arlington Community Foundation website.

“The fund will provide need-based scholarships to graduates of Arlington County’s public high schools,” according to the foundation. “Braylon’s siblings, Bryan and Kerry, and his parents firmly believe that this scholarship fund will perpetuate one of Braylon’s passions, which was to lift up those in need.”

His coach is retiring Meade’s jersey number, 22, and before every game, his teammates will carry out the special handshakes he had for every player and hug his parents.

Dobson says he has already noticed teammates stepping up to try to do what Braylon did for the team.

“Kids who never said a word are now leading the huddle and calling out drills,” he said. “Everybody is doing it as a team.”

But Meade was more than just his sport. His friends and coaches tell ARLnow he worked hard off the court, had a sense of humor and a nerdy side. His girlfriend of three years, Christine Wilson, remembers him as a loyal, communicative boyfriend and a great conversationalist.

“He was such a gentleman and always held the door for me, paid for me, drove, and we would get food somewhere and have great conversation as always,” Wilson said. “Our conversations never got boring and we never ran out of things to talk about, even after three years.”

Weiser said Meade was smart, opinionated and enjoyed lively conversations. He watched basketball closely and often had the same insight into a play as a coach would.

“He was right more often than he was wrong,” Weiser said.

Meade tackled academics and basketball with the same intensity. He took all International Baccalaureate classes and tutored teammates if they asked.

“He had the brightest future of all of us, he never did anything wrong and was always there for me,” McIntyre said. “He was the most hardworking dude I knew for sure, whether it was school, basketball, or beating me in ping pong, he would always practice a lot.”

His friends admired that he always made time for his girlfriend. Wilson says he would call her every night to ask when they would hang out.

“His love language was quality time, so spending time together was super important for us,” she said. “He would always say he loved me and called me beautiful even when I was just in sweatpants and no makeup.”

He also understood the importance of giving back to his community, Dobson says. Meade volunteered at a food pantry, helped kids learn to read at Barrett Elementary School and raised $1,200 for cancer last year.

Even though Meade was known for his competitive edge, he tempered it by being a little goofy. The night before he died, he was playing ping-pong with McIntyre and decided to bet double or nothing, with a McDonald’s shake at stake, on the game. As he lost, he raised the stakes until half the McDonald’s menu was on the line.

When gyms were closed, he and his buddies decided to run drills outside. Meade imitated the distractions of a game by aiming a leaf blower into his friends’ faces and ringing a cowbell.

“He would do anything it took to win, to mess with you,” said Mark’s son and Meade’s teammate, Brian Weiser. “He was a really funny guy.”

When he needed to cool off, he assembled Lego creations. Just before he died, he launched a website to sell his extensive collection, which his friends say he started at two years old and might be worth somewhere between $15,000-$20,000 today. He was also into Star Wars.

“It was funny to see him obsessed with something nerdy, like Star Wars,” Brian said. “It made Braylon Braylon.”

Meade was notably infatuated with University of Michigan, the alma mater of his parents, brother and sister. About half his wardrobe was yellow, blue and dedicated to the Wolverines, and he busted it out for eight-hour pilgrimages to Ann Arbor his family would make for games two to three times a year.

Despite the family ties to Michigan, he was serious enough about his relationship with Wilson to consider bucking tradition for Northeastern, her dream school to which she applied early decision.

“But no matter where he went to college, he always promised he would stay with me and I did too,” she said. “We were so serious and always planned on staying together forever.”