When living civil rights legend Joan Trumpauer Mulholland participated in sit-ins, she carried a Bible with her.

She kept her birth certificate inside “so that they could identify the body,” her son, Loki, said during an event on Saturday at the Black Heritage Museum of Arlington honoring his mother’s activism.

Joan piped up: “I didn’t have a driver’s license or anything like that. So I needed some way for them to know who I am.”

For protesting segregation with lunch counter sit-ins and bus trips known as Freedom Rides, Mulholland was briefly incarcerated in a maximum security prison and hunted by the Ku Klux Klan. In the intervening 60 years, her activism inspired books and documentaries and the creation of the Joan Trumpauer Mulholland Foundation, which provides anti-racist education.

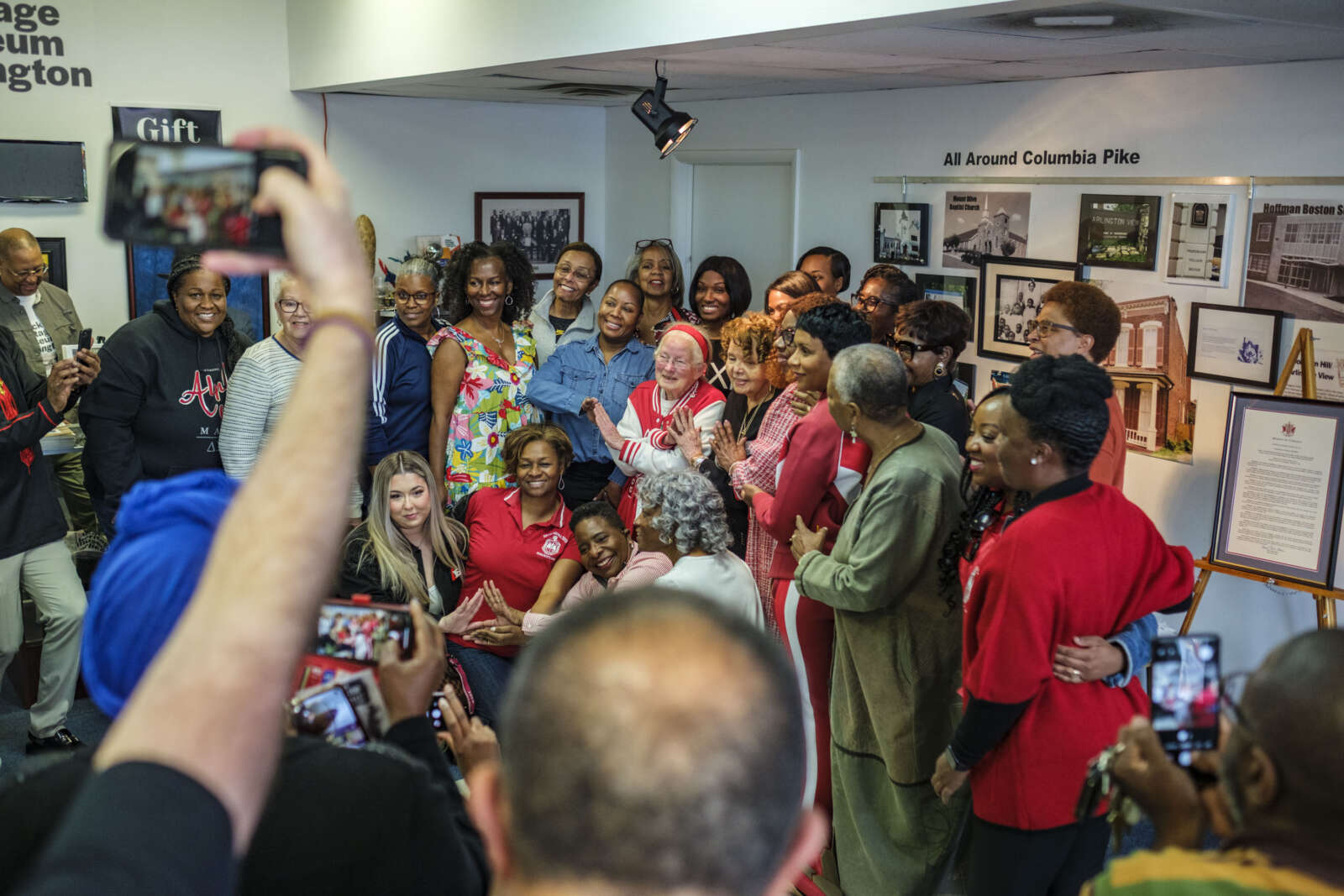

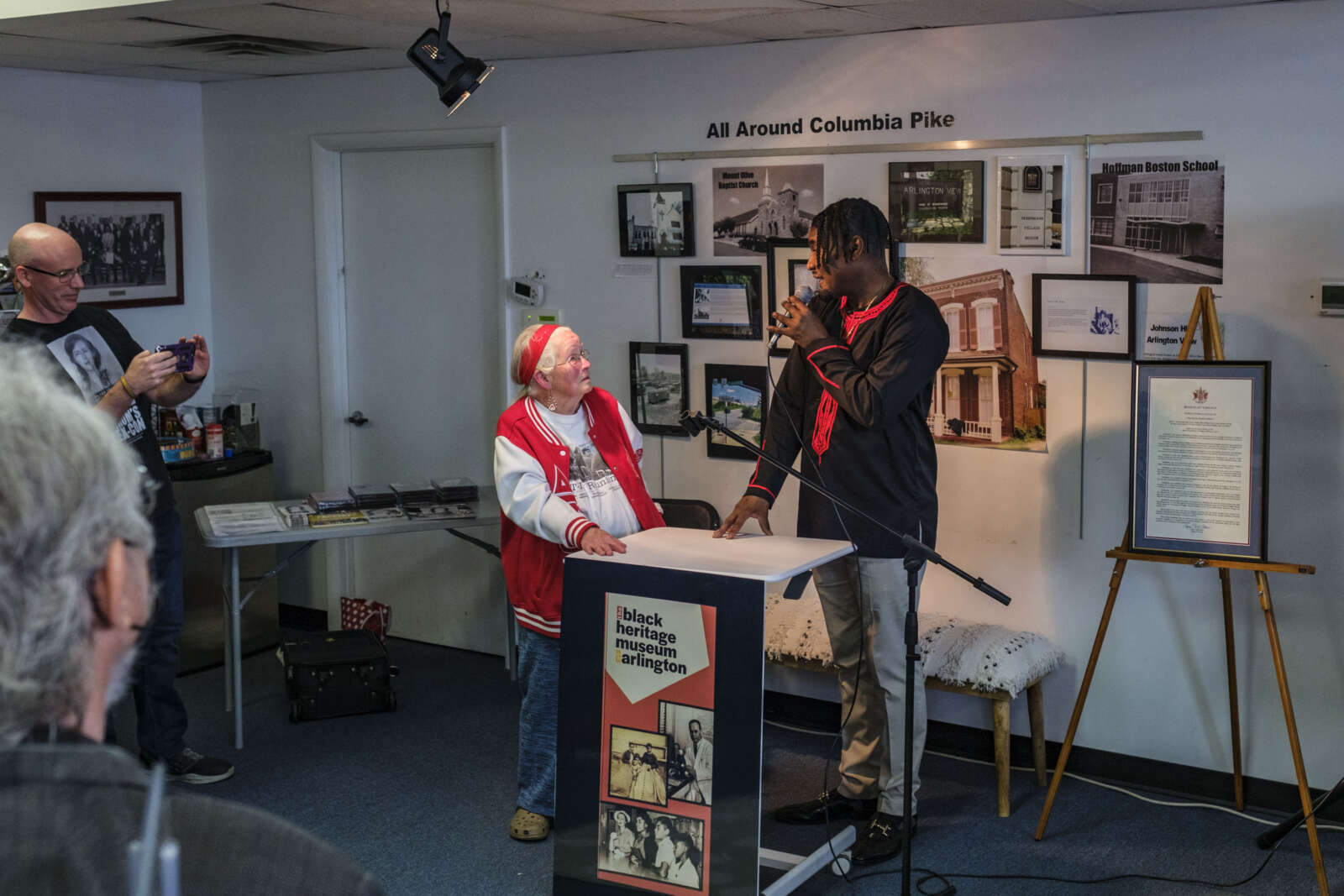

During the event — just shy of the 60th anniversary of a historic sit-in in Jackson, Mississippi, in which Mulholland participated — people gathered at the Columbia Pike museum to hear from her and check out an expanded exhibit with objects from her days as a Freedom Rider.

Just under her Bible, visitors can see memorabilia from the historically Black sorority she joined, Delta Sigma Theta, to advance racial integration.

Nearby is a blue dress she wore during a sit-in at the Woolworth’s in Jackson, Mississippi on May 28, 1963, in which white people attacked her and other Tougaloo College student and faculty demonstrators.

“We want to honor her… because when I talk around and ask people to name some white, anti-racist civil rights leaders, they can’t name anybody but Abe Lincoln, but there’s a lot of them,” museum president Scott Taylor says. “If you don’t know what to do with white privilege, you can look at this right here and she’ll show you.”

Author M. J. O’Brien told attendees that seeing a photo of two demonstrators flanking her — “in all her glory, getting sugar dumped on her, as if she wasn’t sweet enough” — moved him to write a book about the impact of the Jackson Woolworth’s sit-in, “We Shall Not Be Moved.”

Reminiscing, Mulholland said that photo, taken by local newspaper photographer Fred Blackwell, “went worldwide.”

“Back in the days before color photography in the press, it was colorized on the front page above the centerfold of the Paris Match, the most widely read newspaper in Europe,” she recounted.

Mulholland called it “the most integrated picture” of a sit-in, as fellow demonstrators included Anne Moody, a Black woman, and John Hunter Gray, who was of Native American descent.

“We didn’t have any Asian-American students at that time in the school, but we had it pretty well-covered,” she said.

Mulholland said Arlington officials played an important role in turning the tide of the civil rights movement in the region.

Once Arlington’s prosecutor said he would not enforce a law that could lead to the arrest of people who enabled sit-ins — lunch counter operators who did not have a problem serving racially integrated groups, for instance — Falls Church, Alexandria and Fairfax County followed suit.

“So that took care of the lunch counters and eateries in Northern Virginia,” she said.

While the Woolworth’s photo lives on, the activists in the photo, and others Mulholland spent time with, have since passed away. Gray died in 2019; Moody in 2015; and Rep. John Lewis, who Mulholland remembers fondly as always making time to greet her with a hug, died in 2020.

Taylor, the museum director, remarked on these losses and Arlington’s good fortune to still have Mulholland, her memories and her storied belongings.

“For all she’s been through, we’re really blessed to have her,” Taylor said. “I’m not trying to scare you but we’re blessed that you’re still here with us… You went through a lot — all those Freedom Riders did — and so we thank you for your service.”

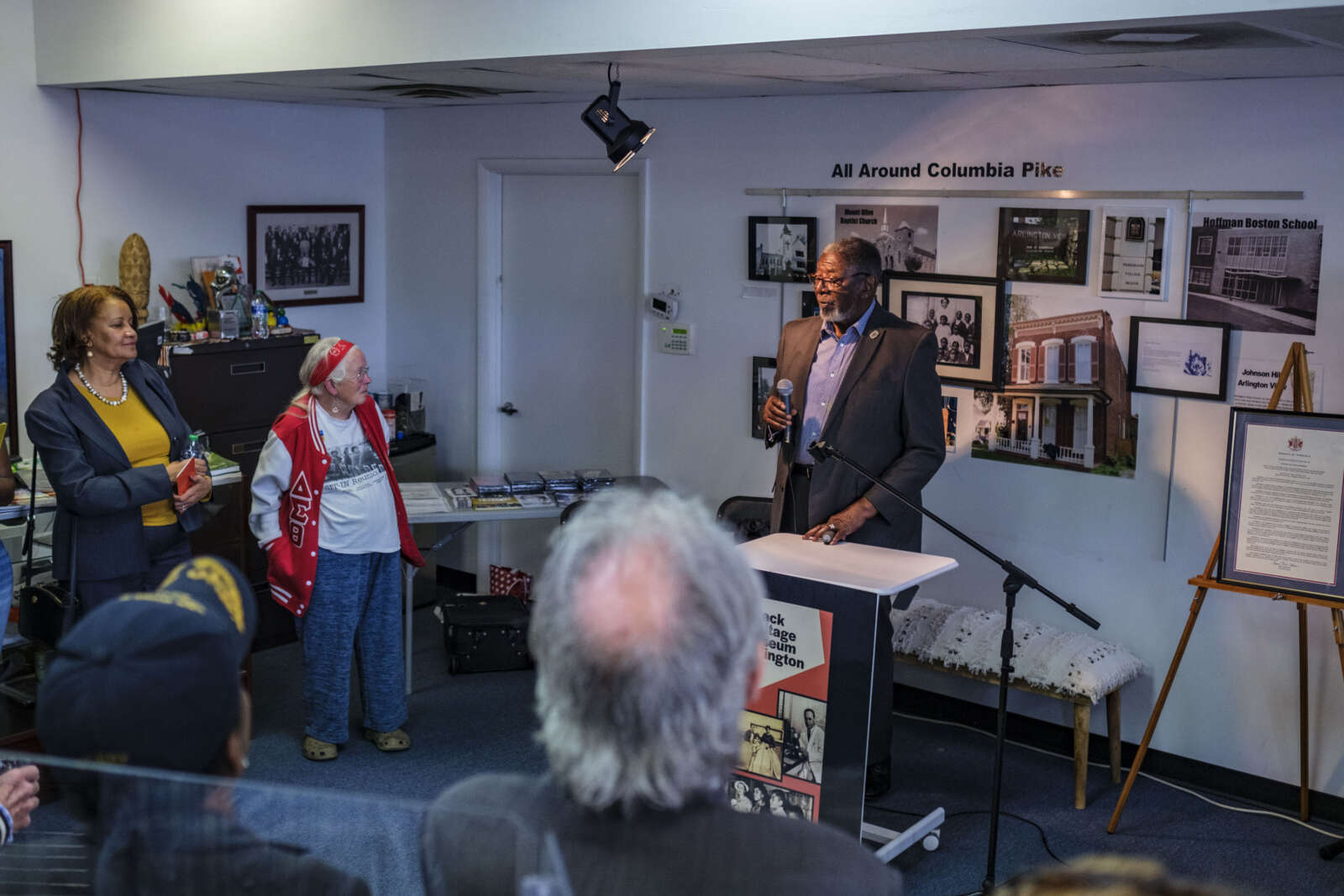

Her activism was recognized this year in the state legislature, too. During the event, Del. Patrick Hope (D-Arlington) read a resolution commending her “inimitable role in the civil rights movement of the 1960s and her ongoing commitment to educating others about equality and advocating for social justice.”

“I’ve always come from the perspective in learning what Joan has accomplished that we can’t educate our community enough about what she’s meant to Arlington, Virginia and the rest of the nation,” Hope said.