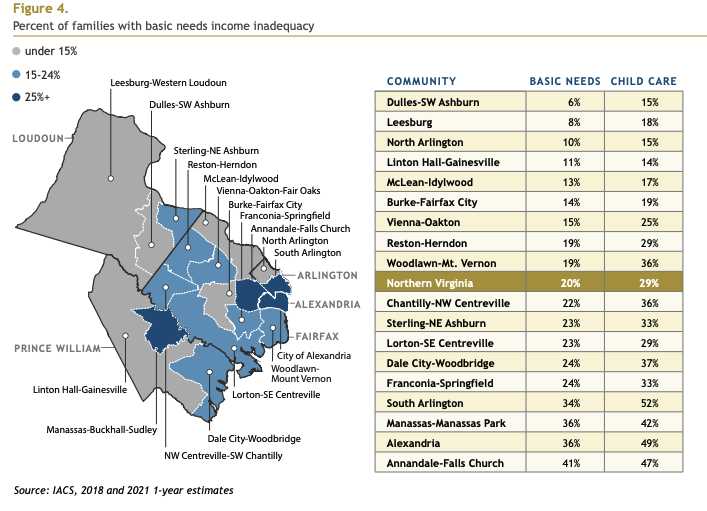

(Updated at 12:45 p.m.) Within Northern Virginia, South Arlington has one of the highest concentrations of families who cannot afford basic needs and childcare.

In this half of the county, 52% of families cannot afford food, housing, medical expenses and childcare, compared to just 15% of families North Arlington, per a new report.

South Arlingtonians are not alone.

About a third of families across Northern Virginia are not earning enough money to subsist, dubbed “income inadequacy” in the report, prepared by Insight Region, the research arm of the nonprofit Community Foundation of Northern Virginia.

The report states that inflation pushed many more families into income inadequacy in the first half of 2023. However, several needs-based nonprofits in Arlington say inflation is not the only contributing factor, pointing also to the rollback of Covid-era benefits.

They tell ARLnow it is time for a systemic overhaul to mitigate increasing income inequality.

“Those basic needs numbers are really concerning to us,” says Brian Marroquín, a program officer at the nonprofit Arlington Community Foundation. “What happens when people lose those benefits is really important… It’s a Catch-22 for many people in our community to try and get ahead while kind of facing the system as it’s set up currently.”

Why families are struggling today

Before the outbreak of Covid, Charles Meng, the CEO of Arlington Food Assistance Center, said his organization typically served about 1,800 to 1,900 families a week. At the height of the pandemic, that number rose to about 2,500 families a week in 2020.

For a short while, the demand for food assistance decreased as case numbers dropped and individuals returned to work. But that changed in February 2022.

“If you’ll remember, inflation started hitting, fuel prices went up first, and then food prices started going up. And since that time, we have seen a steady increase in the number of families coming to us,” Meng told ARLnow. “We’re now serving 3,238 families [a week]… That’s basically a 30% increase from the prior year.”

“I’ve never seen a 30% increase in a year before,” he added.

Meng also attributes the sudden jump partly to inflation, which reduced the purchasing power of already struggling families. He noted the clawing back of other government benefits, such as SNAP, played a role as well.

“These families have effectively gotten a 14% to 15% reduction in their income… They’re paying more for food for a whole bunch of other things,” Meng said.

Data from ACF highlights that over 10,000 households — about 24,000 people — in Arlington make under 30% of the area median income. That translates to about $45,600 for a family of four. AFAC serves many households in that group.

“There’s a lot of families in Arlington County who are hurting,” Meng said.

In addition to SNAP, Marroquín, said the elimination of the Advanced Child Tax Credit, which cut child poverty nearly in half during 2021, also dealt a big blow to Arlington families.

“What that did was it put money in parents’ pockets. At the time, it was particularly important for childcare. Childcare was hard to find and got more expensive as well during the pandemic in 2021,” Marroquín said.

According to the Insight Region report, those most impacted by inflation and the reduction in benefits are primarily Hispanic and Black resident without a bachelor’s degree, who often work in sectors such as food services, construction, personal care or building maintenance.

The report said wages and cost of living have historically moved in tandem in Northern Virginia — until recently. Within the last two years, it said, monthly expenses for a family of four grew by $700 while average wages increased by $100.

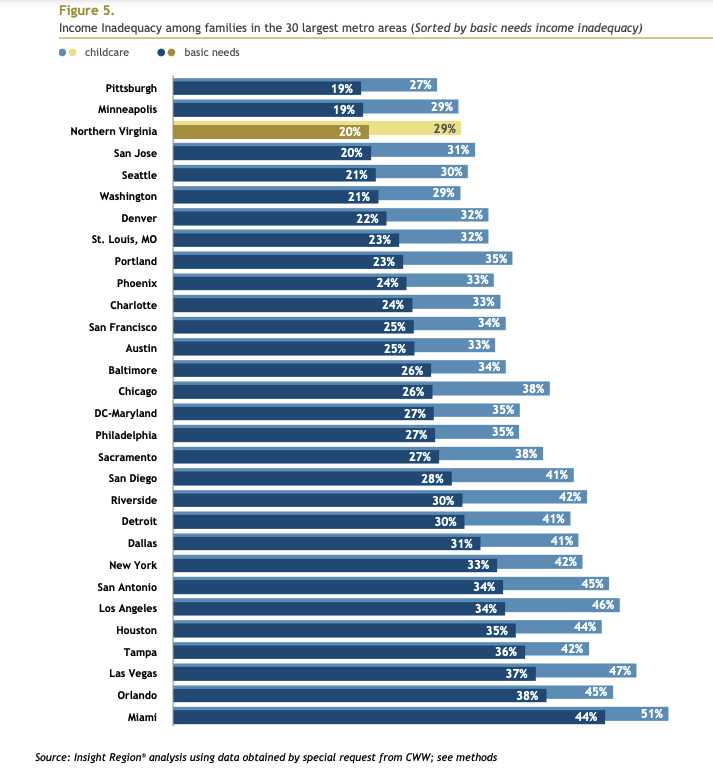

Still, among peer metropolitan areas, Northern Virginia fared better than most of the 30 other areas surveyed, surpassed only by Pittsburgh and Minneapolis.

While Northern Virginia fared well, South Arlington specifically saw income inadequacy rates on-par with Miami, which ranked the worst in terms of purchasing power. There, 44% of families could not cover basic expenses, and an additional half couldn’t afford the cost of childcare.

Solutions at the local and national level

Elizabeth Hughes, director of Insight Region and author of the study, proposed several strategies to address the worsening income inequality her report outlines.

This includes normalizing the acceptance of basic needs assistance, educating parents and children on the benefits of diverse borrowing options, expanding homeownership programs and offering financial counseling to low- and moderate-income families.

Jennifer Owens, the president and CEO of ACF, argued that to adequately tackle the issue of income inadequacy, further legislative measures are needed at both local and federal levels.

For example, in Arlington, Owens said the county could expand or loosen restrictions on its Housing Grants program, which provides rental assistance to low-income Arlington residents earning $35,000 or under.

“These are really structural problems that can be can be mitigated somewhat from local policy,” Owens said.

Nevertheless, Owens and Marroquín underscored the limitations of local efforts to addressing structural inequalities. To address these gaps, they advocated for a federal guaranteed income program, pointing to the ACF’s 2021 guaranteed income pilot as strong evidence that such initiatives could significantly help families lift themselves out of poverty.

“And many of our folks reported that this was a stress relief because they were struggling with the high cost of groceries, the high cost of — if they did have a car — of gas,” Marroquín said. “If we had a federal policy… Not only would people have more money in their pockets, which would facilitate various aspects of life, but their overall wellness, sense of optimism, and income could also dramatically improve.”