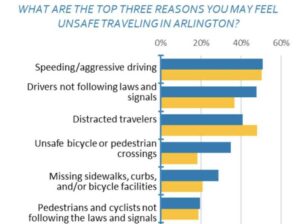

High speeds, traffic scofflaws and distracted drivers are the top three reasons people feel unsafe when traveling around Arlington.

That is according to the county’s latest Vision Zero mid-year report, which summarized how Arlingtonians responded to online and in-person surveys about their top concerns as travelers.

County data on fatal and severe-injury crashes appear to back that up. Among speeding, distracted driving and alcohol, speeding leads the pack as a factor in serious crashes.

County data on fatal and severe-injury crashes appear to back that up. Among speeding, distracted driving and alcohol, speeding leads the pack as a factor in serious crashes.

To tackle speeding — and one day, other traffic violations — Arlington County is laser-focused on automated enforcement. The road to get there, however, is long and some goals could take years of politicking to achieve.

First, the county has to implement speed cameras in school and work zones, which the Arlington County Board authorized in January 2022, shortly after the General Assembly permitted this.

Although Arlington is still working on procuring a contract for speed cameras, the County Board, the Vision Zero team and ACPD are working on expanding the use of speed cameras by including it among legislative priorities in the upcoming General Assembly session.

This could be an uphill battle, as some local legislators told ARLnow there is not yet an appetite in Richmond for widespread automated enforcement.

“The General Assembly has been reticent to allow full use of red light cameras,” said Sen. Adam Ebbin. “I think there might be some hesitancy to having fully automated enforcement, in general.”

Still, the county is pursuing automated enforcement to influence driver behavior when police are not present, lower its reliance on in-person enforcement and reduce potentially adverse interactions with police.

“They’re doing everything they can with what they’ve got right now,” says Vision Zero Coordinator Christine Baker, of the traffic enforcement Arlington County Police Department currently conducts. “We’re both just really hoping for more automation to help keep that progress toward better behaviors.”

Automation would also “let officers do the work that they need to do and leave the traffic enforcement up to ubiquitous, unbiased technologies,” she said.

Mike Doyle, the president of Northern Virginia Families for Safer Streets, agrees that it would limit potential racial bias and escalation in routine stops as well as alleviate police staffing shortages.

“Technology, with a photo and sending the ticket to the person, mitigates the risk of the officer,” he said.

Cameras would be effective, he says, “as long as the speed cameras are balanced in terms of equity: we can’t put them just in all the poor sections of town — they have to be where the speeding is.”

ARLnow asked ACPD whether it supports more cameras or has concerns about the hours officers might have to dedicate to reviewing footage.

Police spokeswoman Ashley Savage says the department “will continue to work collaboratively with the County on any future legislative changes to automated enforcement programs.”

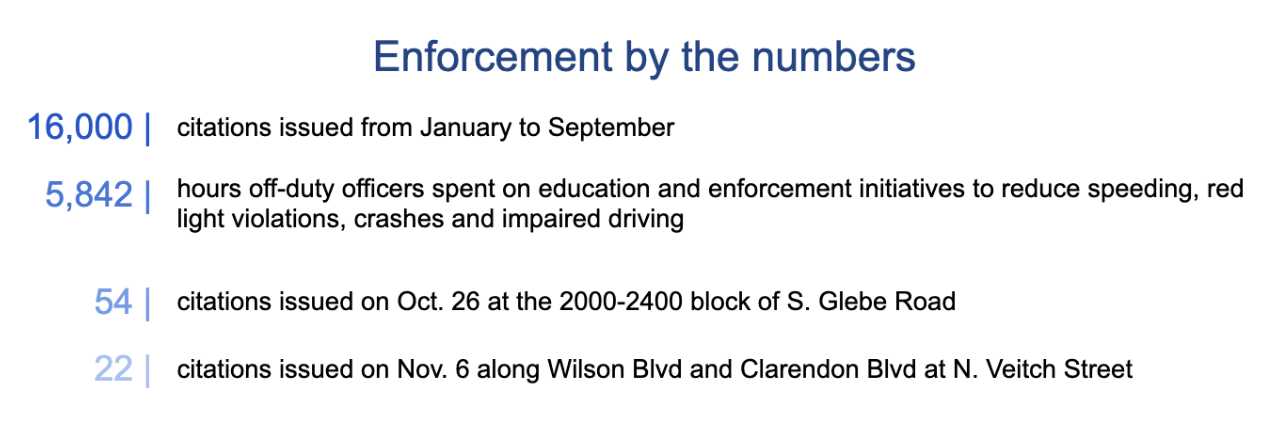

ACPD reports keeping busy with enforcement

Despite staffing concerns — and scaling back operations due to low numbers — ACPD says it is committed to traffic enforcement and considers it a key safety initiative.

ACPD is authorized to have 377 officers and currently has a “functional staffing level” of 278 sworn officers, down from 284 this fall. Sworn offices can stop people for traffic violations and are “expected to meaningfully contribute to the department’s key initiatives,” through education and enforcement, Savage said.

How many are assigned to traffic duties is sensitive information, she said.

“In March 2022, the department announced service changes due to a reduction in our workforce,” says Savage. “There were no key impacts to transportation safety and the department reaffirmed our commitment to ensuring the orderly flow of traffic in the County while conducting transportation safety enforcement and education campaigns.”

ACPD’s Special Operations Section conducts education and enforcement in “identified areas of concern with the goal of voluntary compliance when police are not present, Savage said.

They also address safety concerns, work with Vision Zero staff, deploy variable message boards and other technology, and manage the police department’s participation in local and regional traffic safety programs.

The unit includes civilians who work as parking enforcement agents; traffic directors during events, crashes and emergencies; and school crossing guards.

A slow-moving contract and wariness in Richmond

Nearly two years after the Board authorized speed cameras, they have yet to go up because the county is still “in the procurement process,” says Savage.

“The County will communicate additional information regarding the programs with the community following the completion of the procurement process and prior to implementation of the technology,” she said.

Arlington decided to write its own contract for both speed cameras and its red light cameras, Baker said. Until now, it secured red-light cameras through a rider on a contract held by the city of Houston, which it determined no longer made sense if they bought speed cameras, too.

The county received bids for its contract earlier this year and is in the negotiation process, Baker said.

It appears other jurisdictions are either taking it slow, too, or have yet to consider adopting them.

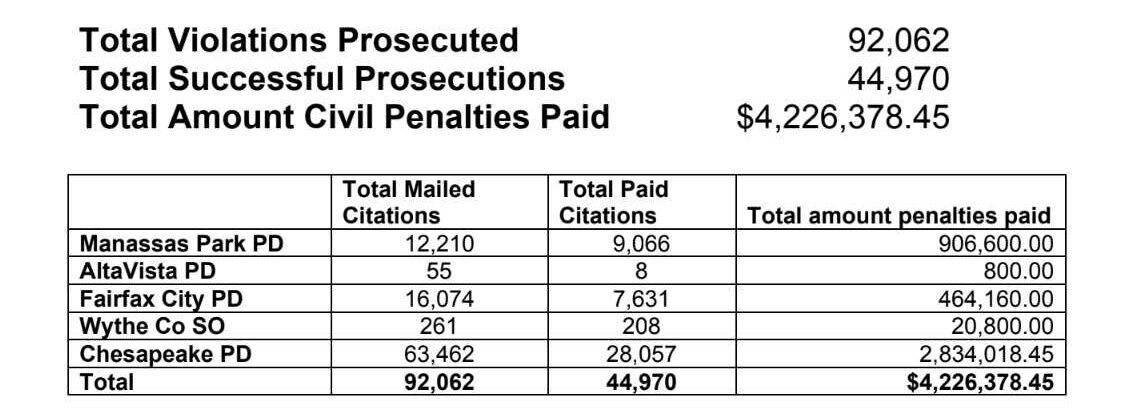

Although the state authorized speed cameras in 2020, only four police departments — those for Manassas Park, Altavista, the City of Fairfax, and Chesapeake — and the Wythe County Sheriff’s Office have adopted them.

In 2022, the most recent year with available data, about half of all violations resulted in a conviction or a fine paid in lieu of a court appearance, according to a Virginia State Police annual report.

Del. Patrick Hope says he would want to know why more localities have not adopted speed cameras before mulling what other automated enforcement to permit.

“I think that we need to find out what the issues are in localities to utilize this new authority,” he said. “I certainly support expanding it.”

It may be a tall order, as Ebbin recalls the decision to allow them in school and work zones was not unanimous.

“I’d be surprised if the General Assembly were to jump from limited red lights and school zones enforcement to full-scale automated enforcement without any restrictions,” he said. “I guess it’d depend on the parameters proposed.”

Baker says Alexandria and Richmond, which both have Vision Zero programs, are both on board with expanded cameras.

“I think there’s support from different progressive jurisdictions throughout the state for this as well,” she said. “I know we’re limited right now with what we can get passed in the legislature. So be thankful for whatever we can get right.”

There may be room for other legislative efforts concurrently, says Baker, noting state code allows Virginia Beach to catch drivers who roll stop signs using cameras.

Doyle would like to see this, too. In “near-miss” data that NVFSS collects, many near-misses are attributed to drivers who roll stop signs, forcing pedestrians to jump out of the way.

Ultimately, Baker says, auto-enforcement could also monitor for other traffic law violations, such as drivers blocking bike lanes or not stopping for pedestrians.

“All that could really help us achieve goals and change behavior but it’s not allowed in code,” Baker said. “So those are things that would be great to explore in the future.”

Cameras: just one hole in a Swiss cheese slice

More automated enforcement would have to be coupled with infrastructure investments — for safer street designs — and sustained police enforcement, says Sam Deutsch, a commentator on transportation safety and urban planning. He calls this the ‘Swiss Cheese’ model of enforcement.

“The first step should be the infrastructure,” he said. “The second step should be the automation because, even if you do build the infrastructure that encourages people to drive slower, some people will still break the rules, and they should be fined. But then the third step is the final resort. You do need some level of in-person enforcement.”

Infrastructure and automation capture the majority of dangerous behaviors, leaving the responsibility to police to hold accountable those who break through the first two layers, who Deutsch says are generally the most dangerous people.

These offenders need more serious consequences, Doyle says.

“We think pedestrian fatalities are a quiet killer: they don’t get that much attention but they’re a major problem, and the consequence — from a criminal point of view — for killing pedestrian is many times a ‘slap on the wrist.’ It’s way out of proportion,” he said.

Doyle says NVFSS has done some education work with policymakers in Richmond about modifying regulations to make striking a pedestrian more consequential, though this is controversial.

But where the rubber meets the road is infrastructure, Deutsch says.

“There’s nothing inherent about America or Americans about why our streets have to be so dangerous,” he said. “Even within America, you look at places like Hoboken, where they’ve… achieved zero traffic deaths… it’s about kind of refusing to accept the status quo.”

For instance, Glencarlyn Civic Association President Julie Lee says for too long, the county has accepted the status quo of traffic conditions, crashes and near-misses on S. Carlin Springs Road near Kenmore Middle School, which has narrow, 4-foot sidewalks. She says residents feel they have been ignored because the solutions are complicated.

“It will require more than speed enforcement but I don’t hold police accountable for the issues we’re having on Carlin Springs Road,” she said. “The issues have to do with the sidewalks and they have to do with the intersections.”

Arlington could take a page from neighboring Alexandria, lowering speeds to 25 mph as the city did on Seminary Road, which feeds into S. Carlin Springs Road. Crashes dropped 41% after the city reduced thru-lanes, added a center turn lane, buffered bike lanes, an in-street shared-use path — in lieu of a sidewalk — and more pedestrian crossings.

Lee would like to see speed enforcement, crossing guards and yellow flashing pedestrian beacons, which can be found along N. Carlin Springs Road through Arlington Forest.

“Those are also expensive and complicated, too, but the bottom line is that the county has kicked the can down the road, and ignored this instead of hitting head on,” she said.

This reporting was supported by the ARLnow Press Club. Join today to support in-depth local journalism — and get an exclusive morning preview of each day’s planned coverage.