(Updated on 1/29/23) Arlington County suffered another defeat last week in the pre-trial proceedings for the Missing Middle lawsuit.

It appealed an earlier court decision that the 10 residents suing Arlington County — alleging the County Board illegally approved the Missing Middle zoning amendments — have standing to do so.

Last Thursday, Judge David Schell denied the latest motion, meaning the court proceedings will continue forward with a trial this July, according to a press release from Arlington Neighbors for Neighborhoods, the LLC funding the litigation efforts on behalf of the 10 residents.

“[The] ruling is another win for Arlington homeowners and another loss for the County, which now has brought in the big guns, hiring at Arlington taxpayers’ expense, Gentry Locke, a Roanoke law firm, to assist with the case,” said Arlington Neighbors for Neighborhoods spokesman Dan Creedon in a statement. “The judge recognized that the County’s delay tactics would harm the plaintiffs as MMH/EHO buildings would be built pending an appeal.”

Schell said that granting the county’s motion could delay the trial for two or more years, per the release. This may not be in the county’s interest, either, the judge noted, musing that, should the county lose at trial, developers may tear down EHO structures — Expanded Housing Option, another term for Missing Middle — built while the case was pending.

Two land use attorneys recently broke down the details of the lawsuit in a panel hosted by the Arlington Committee of 100 last week. They walked through the county’s alleged procedural missteps, as asserted by lawyers for the plaintiffs.

“The reason for the procedural requirements aren’t to create arbitrary processes to do these things. The processes set forth in the code are there to ensure there’s adequate public discourse on the impact of what is being proposed,” said attorney Tad Lunger.

For major zoning map amendments, such as those allowing lower-density multifamily housing in previously single-family-only zones, Lunger says Virginia code requires a public discourse on how the changes would impact transportation and infrastructure and how those costs would be borne by residents.

“These things weren’t discussed at that level in Arlington,” he said.

One Missing Middle proponent, affordable housing advocate Michelle Winters, is optimistic that, should the county lose on procedural grounds, it could re-adopt the ordinance and resume approving EHOs.

“It’s very easy to cure procedural deficiencies. You change your process and re-adopt it. This is exactly what Fairfax County did,” Winters said.

The Virginia Supreme Court struck down Fairfax County’s zoning ordinance early last year but within a couple of months, the Board of Supervisors adopted the same ordinance after fixing the procedural issues. The changes were approved in a virtual meeting in 2021, at a time when virtual meetings were only to discuss essential government functions and services.

Pointing to the ordinances in Fairfax and similar changes Alexandria adopted late last year, she said it is clear these types of changes are here to stay, come what may from a lawsuit alleging Arlington County enacted its ordinance poorly.

“In Alexandria, what is relevant is the reflection of the shift that we’re seeing in America — not only in our region but in America — that this type of change absolutely needs to happen and no matter what you do to this particular ordinance, if this ordinance isn’t in place, something like it will be in place to replace it,” Winters said.

Raighne “Renny” Delaney, an attorney with Bean, Kinney & Korman, argued the lawsuit could have more far-ranging political impacts.

“If [the residents] win, do the people who want to propose [new ordinances] have the political wherewithal to do it again and go through the procedures in a correct way?” he said. “Yes, procedural problems can be fixed, but they can also cause a host of other issues and there’s elections in between that may affect the outcome.”

Representing Arlingtonians for Our Sustainable Future, a group that strenuously opposed Missing Middle, panelist Jon Ware provided an overview on where EHO approval and development stand today.

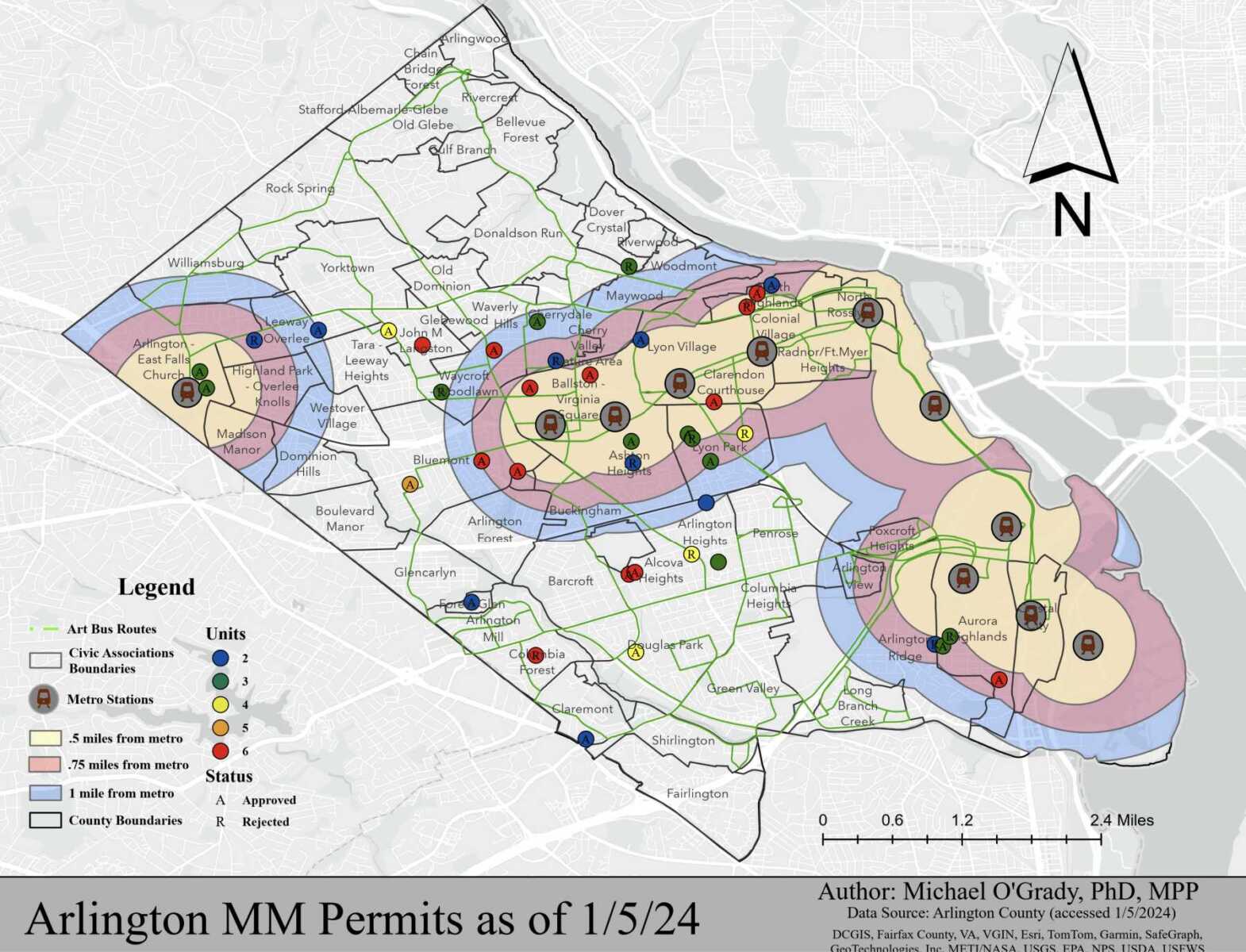

The permits are localized a handful of neighborhoods, including Alcova Heights, Aurora Highlands, Bluemont and Lyon Park, he said. Notably, many of the permits are within a mile of Metro stations.

Most approved permits are for six-plexes and a majority of these are on the county’s smaller lot sizes, ranging from 5,000 to 6,000 square feet, Ware said.

He highlighted one approved 6-plex in Aurora Highlands that would, if built, be about twice the size of the largest new home in the neighborhood.

Ware argued the pace of permit approval portends a development pace exceeding initial county projections.

“The county paid $100,000 to a pair of non-economist consultants… [who] said it would only be 19-21 lots per year, dispersed throughout the county. The county turned around and told other staff, ‘This is the pace, because it’s so slow, we don’t need to do the further deep analysis about what the impact might be,'” Ware said. “Instead of 19-21 per year, we saw 50 applications in just the first six months, 26 of which have been approved.”