This reporting was supported by the ARLnow Press Club. Join today to support in-depth local journalism — and get an exclusive morning preview of each day’s planned coverage.

The Arlington County Sheriff’s Office is facing mounting pressure from personnel, inmates and the NAACP to address worsening conditions at the county jail.

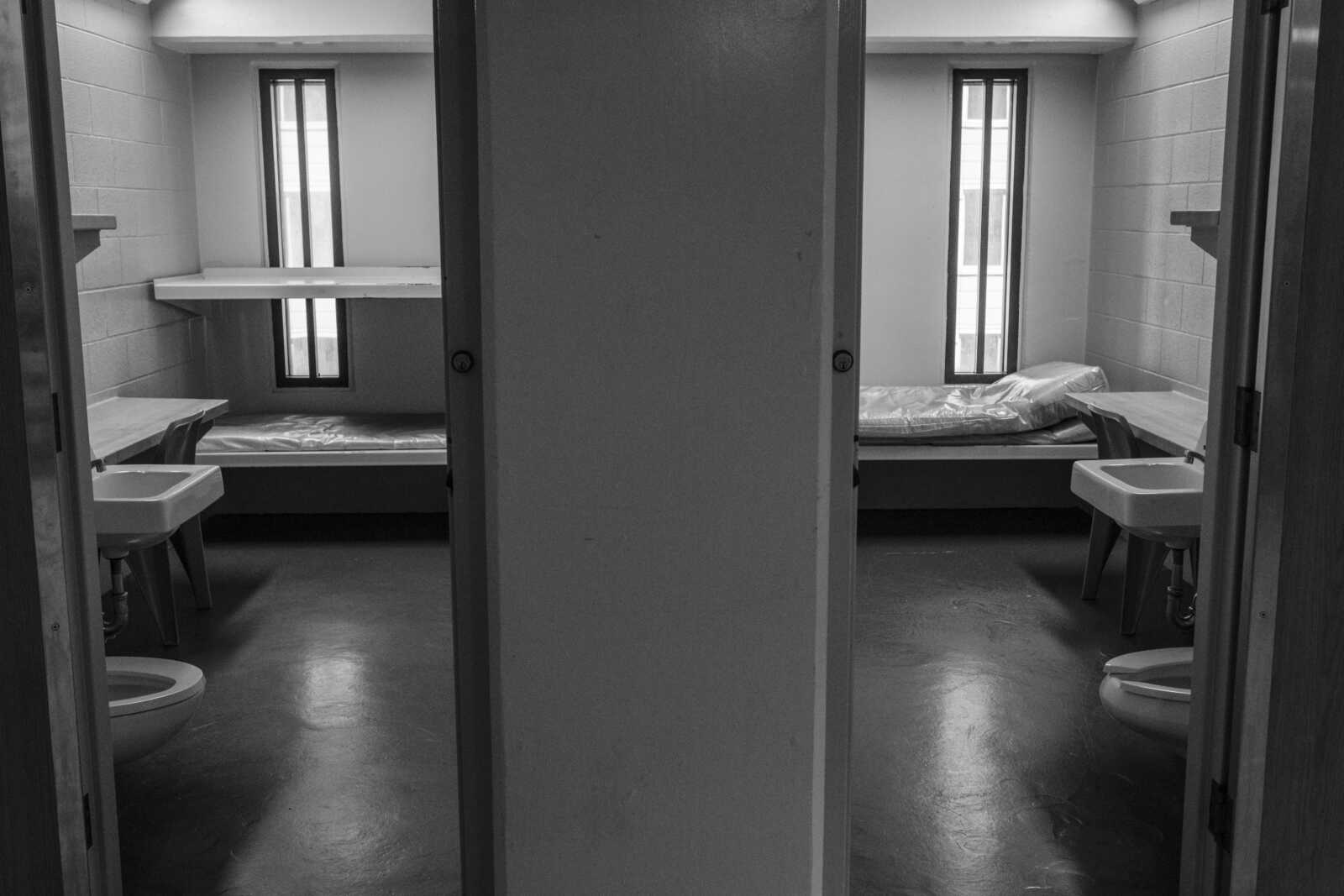

Current and former deputies, along with a former inmate, claim that chronic staffing shortages inside the jail have led to inmates being confined to their cells for up to 21 hours daily, deputies not following proper protocols, the mismanagement of medication dosages and inmates not being allowed to take showers.

A jail-based staff-led anonymous survey obtained by ARLnow chalks up the retention challenges to issues with leadership, salary, and work conditions, particularly mandatory overtime.

Sources caution that without intervention, the ongoing staff shortages at the jail pose a significant safety risk to deputies and inmates.

Nine deaths in eight years

On Oct. 2, 2020, Arlington County Jail inmate Darryl Becton, 46, was found unconscious in his cell at 4:17 p.m.

Twenty-eight minutes later, medics pronounced him dead at the scene. His death, later attributed to hypertensive cardiovascular disease, complicated by opiate withdrawal, generated significant county and community attention.

In the wake of Becton’s death, his family filed a $10 million wrongful death lawsuit against former Arlington County Sheriff Beth Arthur, Corizon Correctional Health — the jail’s now-former medical provider — and four medical staff members, citing negligence in properly monitoring his high blood pressure and withdrawal symptoms.

A Corizon nurse was charged in connection with Becton’s death but was later found not guilty.

In response, the jail hired a new medical provider, updated its safety protocols and announced it would equip some inmates with biometric wrist monitors tracking their vital signs. Current Sheriff Jose Quiroz piloted these wrist monitors this fall, distributing them to inmates in the jail’s medical unit.

“We’re going to pilot it with the folks in our infirmary who are, in my eyes, the most critical, the most vulnerable, whether it’s pre-existing medical conditions or anyone going through withdrawals or detox,” Quiroz told ARLnow during an interview in September 2023. “And so, I’m definitely committed to that.”

Like Becton, Jermaine Culbreath, a former Arlington County Detention Facility inmate, also suffers from high blood pressure. Although prescribed blood pressure medication during his incarceration, he told ARLnow he did not receive a wrist monitor.

Culbreath also alleges that on multiple occasions, the jail’s medical staff either failed to deliver his medication promptly in the morning or did not deliver it at all.

“If they did give it to me, they’d give me the medicine in the afternoon,” he told ARLnow. “Like, I’m supposed to take it in the morning because if I try to take this medicine after a certain hour, I can overdose because this is like me taking it twice.”

Over the last eight years, nine inmates — many of whom previously experienced homelessness — have died while in the custody of the Sheriff’s Office. The two most recent incidents this year involved 73-year-old Abonesh Woldegeorges and 55-year-old David Gerhard, both of whom were found unresponsive in their cells.

Gerhard died after going into cardiac arrest, and Woldergeorges died after falling out of her bunk and hitting her head, according to the Sheriff’s Office. Investigations into both cases are currently ongoing.

How staff shortages figure into current conditions

While it’s difficult to say they are directly related, sources, including Culbreath and retired Arlington County sheriff’s deputy Wanda Younger, trace the recent deaths and lapses to staffing shortages within ACSO and the impact they have on jail operations.

“There have been nine deaths in eight years,” Younger told ARLnow. “This is showing signs of the exacerbation that’s happening with the lack of staff, the daily shortages and these daily lockdowns.”

Situated directly opposite the Arlington County Justice Center on N. Courthouse Road, the 11-story jail, on average, houses about 364 inmates who are managed by a team of approximately 270 sworn deputies and civilian staff.

At any given time, the jail is supervised by up to 35 personnel — including 30 deputies, four sergeants, and one lieutenant — who work 12 to 12.5-hour shifts, Maj. Jonathan Burgess told ARLnow during a tour of the detention facility in September 2023.

Theoretically, 35 deputies per shift would be ample, but daily staffing levels are reportedly lower than that, says Younger, referencing conversations with those currently working inside.

“I’ve been told that the Sheriff’s Office is short-staffed almost on a daily basis,” she said.

Before her retirement, Younger, who previously lost her bid for county Sheriff last year, served as a shift commander at the jail. In this role, she had the authority to initiate “modified operations” — changing or limiting inmate movements and routines — when staffing levels decreased to 27.

If staffing dropped to 26 or below, command staff would have the discretion to enter into a lockdown, during which detainees were only allowed out in “manageable groups” for two hours during the day and one hour at night.

Sheriff’s Office spokesperson Amy Meehan declined to comment on the current minimum staffing requirements, citing state law, which she claims exempts the Sheriff’s Office from disclosing such figures.

Younger argues that if the Sheriff’s Office met minimum staffing, “there wouldn’t be a need for any lockdowns.”

Sheriff Quiroz acknowledged that staffing shortages have contributed to more frequent lockdowns. He argues these lockdowns and modified operations are necessary for the safety of staff and inmates.

“If I let the entire jail out, and I don’t have enough staff, God forbid, there’s an emergency, I have to answer to that loved one if something happened,” he said.

Quiroz attributes the staffing shortages partly to pay disparities between deputies and county police officers, noting that deputies are paid less despite having “more certifications.”

“We don’t get paid the same as the police department. And while their job is extremely important, so is ours because [they] bring arrests to our jail, to Arlington jail,” he said.

The minimum starting salary for a deputy in 2023 was $62,504, compared to $68,503 for a police officer, per the county’s adopted budget for the 2024 fiscal year.

The pay makes living in Arlington difficult, leading many deputies to commute from other counties and states — or seek jobs closer to home, Quiroz says.

“A lot of my staff don’t live in Arlington,” he said. “They commute from Stafford; Fauquier; West Virginia; La Plata, Maryland; Leesburg and Waldorf, Maryland.”

While pay may be a source of consternation, the 90 staff who responded to the anonymous survey said other issues are equally to blame: among them, ineffective leadership, understaffing, inadequate training, mandatory overtime and extreme fatigue among lower-level staff.

“Command staff must respect work/life boundaries,” said one respondent with 12-15 years of experience working in the Sheriff’s Office. “Mandatory overtime for over three years is not sustainable, as is seen with low staff retention/morale.”

Those who cited “leadership” or “working conditions” as their primary concern also linked the rising number of jail lockdowns to overworked staff frequently calling in sick or taking unpaid time off.

“We’re tired,” said a survey participant with four to seven years of experience. “It is visibly shown by the sick calls, tiredness of staff, and people leaving the job. We’re overworked and underpaid.”

When asked if ACSO was aware of the survey, Meehan said Quiroz gave three staff the go-ahead to conduct it. The results were shared with staff and discussed among Quiroz and command staff.

“The Sheriff has not shied away from sharing challenges that we continue to face daily,” she continued. “While we acknowledge the issues, our commitment to staff and those incarcerated remains unwavering.”

This past Friday, in a nod to this commitment, ACSO launched a quarterly newsletter “aimed at fostering transparency and communication with the residents of Arlington,” outlining the office’s efforts to make the jail safe and prioritize staff wellness and professional growth.

For the anonymous staff, reaching those goals will require greater respect and transparency from management toward rank-and-file, increased pay and greater accountability for inmates who break rules, among other changes.

What happens during a lockdown

As a consequence of the staff shortages, Culbreath said lockdowns happened almost weekly, if not daily when he was incarcerated.

“So, every time the sprinkler head breaks or somebody upstairs does something, or there’s a fight, they lock us down, they lock us down, they lock us down,” Culbreath said. “We were getting locked down multiple times throughout the day.”

The lockdowns became so frequent that Culbreath’s wife, Chelsea Harty, began to keep track of them. She said her husband experienced 27 lockdowns between June and August, most of which lasted about 21 hours.

Although inmates were usually allowed at least 2-3 hours a day of recreational time outside their cell, Culbreath said it was not enough.

“I had to start working out and thinking of just happy things for me not to get so depressed and just like break down,” Culbreath said. “Locked down in an eight by ten cell 12-20 hours, that sucks. It’s terrible.”

Emphasizing the extreme steps he took to manage his depression, Culbreath said he recorded five miles on his step counter in a single day while pacing in his cell during an extended lockdown.

“You shouldn’t have to live like that,” he said. “My dog gets more freedom than we get. Animals at the zoo get more freedom than we do being incarcerated.”

Arlington’s chief public defender, Brad Haywood, says several clients also reported frequent lockdowns, which affected their mental health.

“Our clients are supposed to have rec time,” Haywood told ARLnow. “They are supposed to have time outside of their cells. That’s important for the mental health of people who are incarcerated.”

Numerous studies have linked solitary confinement to adverse health outcomes. One by the National Institute of Health found that confining someone to a cell alone for 22 hours or more per day can heighten psychological distress and also lead to physical effects, including weight fluctuation.

As of October 2023, more than half of inmates were taking psychotropic medications for various mental health disorders, according to Meehan.

Haywood emphasized that inadequate out-of-cell time can aggravate the mental health of inmates receiving treatment.

“It’s actually sensory deprivation,” he said. “Sensory deprivation is actually well known to cause even things like psychosis. So, the more you kind of go in that direction, the more harmful incarceration is to clients.”

When asked about the frequency of lockdowns at the jail, the Sheriff’s Office declined to comment, claiming those numbers are also subject to state exemption laws.

Culbreath noted that lockdowns not only affected inmates but also took a toll on deputy morale. He said that some deputies felt “bored” during these times, which he believes led to some staff members resigning.

“I’ve talked to several of them, and they’re like, ‘Man, I’m leaving this shit… I’m not gonna put up with this.’ They’re bored just sitting there,” he said.

Culbreath also alleged that, during lockdowns, deputies frequently failed to make their rounds punctually, withheld shower privileges from inmates, and sometimes ignored inmates even if they activated the emergency call box in their cells.

“There is a light that sits up at the top that blinks to let you know somebody hit the emergency button, and it will pop up which cell on [the deputy’s] screen,” Culbreath said. “You hit your button, though, and then they turn it off.”

In response to ARLnow’s inquiries about inmates’ rights during a lockdown, Meehan said that irrespective of a lockdown or modified operation, inmates are entitled to medical care, legal assistance, religious freedom and basic necessities, which include access to showers.

Two inmates, one health condition

While Culbreath said the frequent number of lockdowns were “torture,” he expressed even greater concern about how the jail’s staff attended to his medical issues.

Several months into his incarceration, he started experiencing a tingling sensation in his hands. Initially dismissing it, Culbreath became concerned after it continued for weeks and asked to see the jail’s medical staff.

Culbreath said a nurse eventually came to check his blood pressure, after which she promptly escorted him down to the medical unit because his blood pressure, she said, was “way too high.”

“It kind of freaked me out,” Culbreath said.

Before his August 2021 arrest, Culbreath acknowledged he was addicted to PCP, a hallucinogenic, dissociative drug that is associated with high blood pressure, according to American Addiction Centers. He pleaded guilty to multiple charges, including driving under the influence, driving on a suspended license and possession of a Schedule I/II drug.

Culbreath was prescribed various medications to lower his blood pressure and was told by medical staff a nurse would come by regularly to check his blood pressure. However, there were instances when several weeks passed without any check-up, says Culbreath.

“Nurses that work in the jail have not been checking Jermaine Culbreath’s blood pressure [and] he has filed three sick calls, not once has anything been checked,” Harty said in an email addressed to Chief Deputy Tara Johnson on July 31, 2023.

Harty also claims in the email to Johnson that Culbreath consistently received the same meal tray as other inmates when he was supposed to get a “diet tray” with low-sodium foods.

“I had to tell my wife to send me more money so I could eat to commissary because I’m not eating the trays,” Culbreath said.

Culbreath says he filed four grievances with the jail about his medical care, which he claims “went unanswered.” Harty, meanwhile, sent numerous emails to staff and filed an official complaint with ACSO on June 22, 2023.

In her complaint, she also noted that deputies were often nodding off during their shifts or preoccupied with their phones during lockdowns.

In several voicemails to Harty obtained by ARLnow, Johnson claimed she had spoken with Culbreath and was addressing the issue.

In a letter from Johnson on June 26, 2023, also obtained by ARLnow, she refuted the claims that Culbreath had consistently received low-sodium foods and argued he was allotted adequate time for recreation during lockdown days.

She also said that Harty’s claim that deputies were on their phones “is not accurate.”

“We have supervisors and cameras in the entire jail, and it is easy to identify concerns of this,” Johnson said in the letter.

Feeling she had little recourse, Harty contacted the Arlington branch of the NAACP for assistance. After she did, Harty said her husband started getting his medication on time.

“I was advocating for all inmates,” Harty said.

Grievances and legal action

Days after Becton died in 2020, the local NAACP branch called for an independent investigation into his death.

Last month, the general counsel for the national NAACP upped the ante, calling for an independent U.S. Department of Justice investigation after hearing complaints from several inmates and jail staff. Invoking the nine deaths in eight years, the NAACP argued the jail was violating the civil rights of inmates.

“The conditions inside the jail are contributing to deteriorating state of mental health for staff but also the residents,” NAACP Arlington Branch President Mike Hemminger told ARLnow.

“It’s the position of NAACP that unless something drastic happens at the detention center, we’re going to continue to see escalating and level catastrophes occur within the detention center,” Hemminger continued.

Culbreath said he shares the NAACP’s belief that the lives of his peers still in jail are at risk and plans to take legal action as well.

“I’m glad I’m out of there,” he said. “And I just hope that they just changed for the people that’s in there… I mean, it’s to say you shouldn’t have to live like that. I understand that you’re incarcerated; you’re paying debt back to society. But God dang, man.”