Making Room is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

Making Room is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

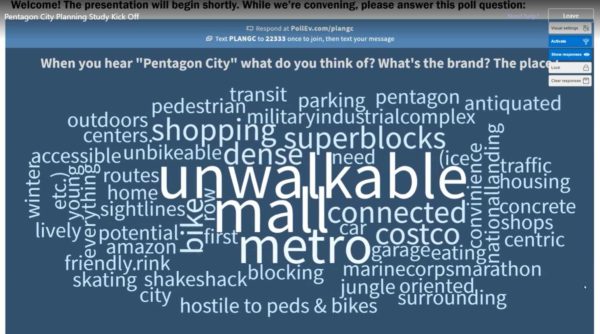

Crystal City and Pentagon City have long been a patchwork of single-family homes, dense retail, and aging office buildings, cut up by wide roads. Nothing divides the neighborhoods more than Route 1, which is elevated as it comes from DC into Arlington.

Two years ago, when Amazon selected Arlington for its second headquarters, it pushed to include a plan to bring more sections of the highway to ground level. Although many urban highways should be removed, the Route 1 plan is imperiled by the decision to maintain current traffic volume.

Without an absolute commitment to lower speeds, reduce car travel lanes, build protected bike infrastructure, and reduce the total width, a lowered highway is a death trap running through our front yard.

Route 1 is a dividing line between Pentagon City and Crystal City, cutting people off from recreation, shopping, and jobs, to say nothing of the Metro Station and the Mount Vernon Trail. The elevated portions of the highway allow pedestrians and cyclists easier access. Many of my neighbors share the fear that an at-grade Route 1 will be a further impediment to connectivity.

The National Landing BID has been one of the leading forces in favor of the new “urban boulevard.” They assured us that lowering the highway would enhance connectivity and improve the road for all users. They emphasized multimodal improvements and likened their vision to Connecticut Avenue in D.C. or the Michigan Ave in Chicago. Left unstated is that this is only possible with a significant reduction in traffic volume through Crystal City.

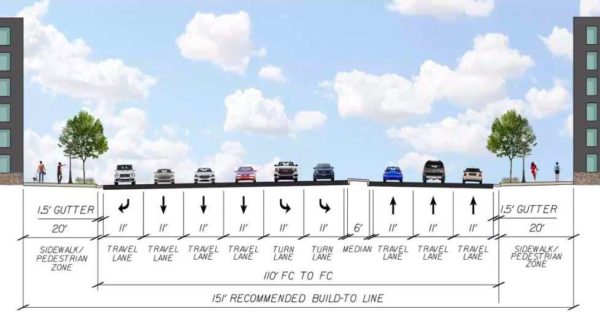

Now VDOT shared a preview of its vision for Route 1, confirming everything locals feared and expected. In contrast to the vision championed by the BID (only 5 or 6 lanes, with protected bike lanes and wide sidewalks), VDOT proposes expanding the highway with 9 lanes and no bike infrastructure. The plan includes two left turn lanes, against the explicit wishes of the BID. To appease neighbors worried about commuter traffic cutting through nearby local streets, VDOT has to put drivers’ speed and convenience first.

This outcome is not surprising. VDOT consistently pushes to widen roads and views traffic safety as the need to keep cars moving. Arlington and VDOT are also pursuing a widening project on Route 50/Arlington Blvd, over the objections of adjacent residents and the Transportation Commission, under the auspice of “safety.”

Now that I see VDOT’s rendering alongside the purported study goals, the dissonance is laughable. These 9 lanes of traffic are neither safe nor environmental. They do nothing for transit effectiveness or multimodal accessibility. They do not mend the urban fabric. Instead, VDOT’s plan would put a dangerous, polluting highway through a growing downtown neighborhood.

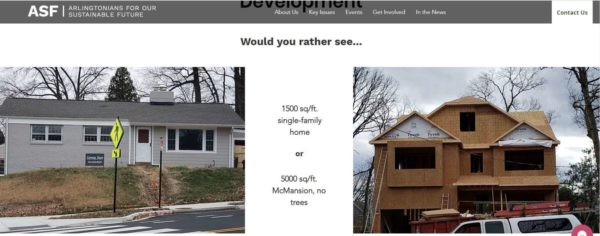

VDOT’s unfortunate reality check might be enough to kill this project altogether. But we can do better than Route 1’s status quo. A committed group of local residents has been exploring alternative ideas, informed by extensive outreach to neighbors. It is time for our elected leaders to get involved and push for a real commitment to safety and connectivity. We can praise Arlington for approving large-scale development, both commercial and residential, to meet obvious demand. But unless we also commit to reducing car traffic, we will fail to bring inclusive, sustainable, humane growth.

Community members can voice their concerns at a public meeting on March 3.

Jane Fiegen Green, an Arlington resident since 2015, proudly rents an apartment in Pentagon City with her family. By day, she is the Membership Director for Food and Water Watch, and by night she tries to navigate the Arlington Way. Opinions here are her own.