Making Room is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

Making Room is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

This piece was co-written by Gillian Burgess.

Next month, the Arlington County Board will approve its Capital Improvement Plan (or CIP) after a truncated process. This critical component of Arlington’s budget outlines the investment that the county will make in infrastructure in the future.

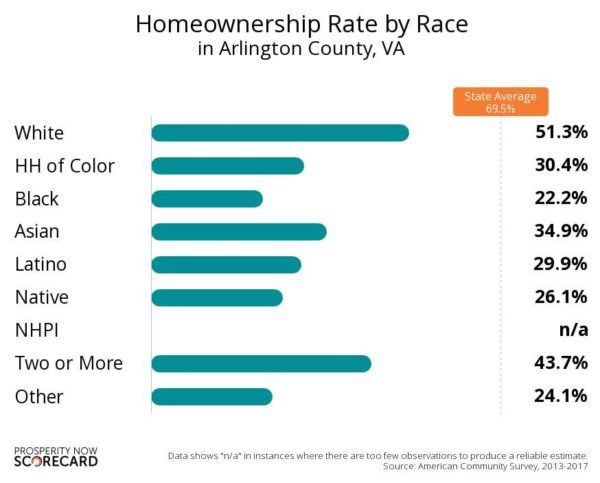

Unfortunately, the County Manager’s proposed CIP budget is setting us up to perpetuate inequities in our infrastructure investments at a time when we should be responding to a crisis by pursuing equity.

The typical CIP budget process involves months of community input. It also typically projects out the investments that the county will make over the next 10 years. This long-term planning is essential for infrastructure projects that will serve residents across the county for many years to come. It is so time-consuming that it typically only happens every other year. The last CIP was adopted in 2018.

However, under the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, County Manager Mark Schwartz has proposed a budget with only one year of investments, with a promise to come back next year with a longer-term (4-6 years) investments. Mr. Schwartz said he was guided by five principles in these making the county’s investments:

- Finish projects that are underway;

- Repair infrastructure that is failing or at the end of its life;

- Meet legal and regulatory obligations;

- Make investments to address the pandemic;

- Implementing the body-worn camera for police, sheriff, and fire marshalls; and

- Invest in strengthening stormwater infrastructure.

The first five categories can be described as “needs and requirements,” but the sixth is the only new investment the county is considering. Funding for the projects come from many sources: grants, specific fees, real estate taxes (through the annual operating budget) and bonds, which the public votes on in November. Many of those sources are restricted in what they can be used for, such as grants for transportation projects.

The Manager’s Proposal leaves new projects that we typically see in the CIP — everything from parks to bike lanes — unfunded and delayed for at least a year. This year, the Manager is recommending a bond referendum of $51 million to fund the first round of stormwater projects. If approved, this would be the first time a bond was issued specifically for stormwater infrastructure (previously, stormwater had been funded by the stormwater tax and utilities bonds).