The following in-depth local reporting was supported by the ARLnow Press Club. Join today to support local journalism and to get an early look at what we’re planning to cover each day.

Marguarite Gooden, who is now in her 70s, remembers the day that her grandfather, “a sage man,” as she describes him, told her something that would forever alter her family’s course.

“Keep the land,” he said.

When she could afford it, she purchased her first childhood home, which her father built on her grandfather’s property. She then purchased her second, larger childhood home, which her father built across what’s now named Langston Blvd, then Lee Highway, when his wife became pregnant with twins.

“I own both properties and I have had the wherewithal to make sure they’re in trusts, and that my kids and grandkids cannot sell them,” Gooden tells ARLnow.

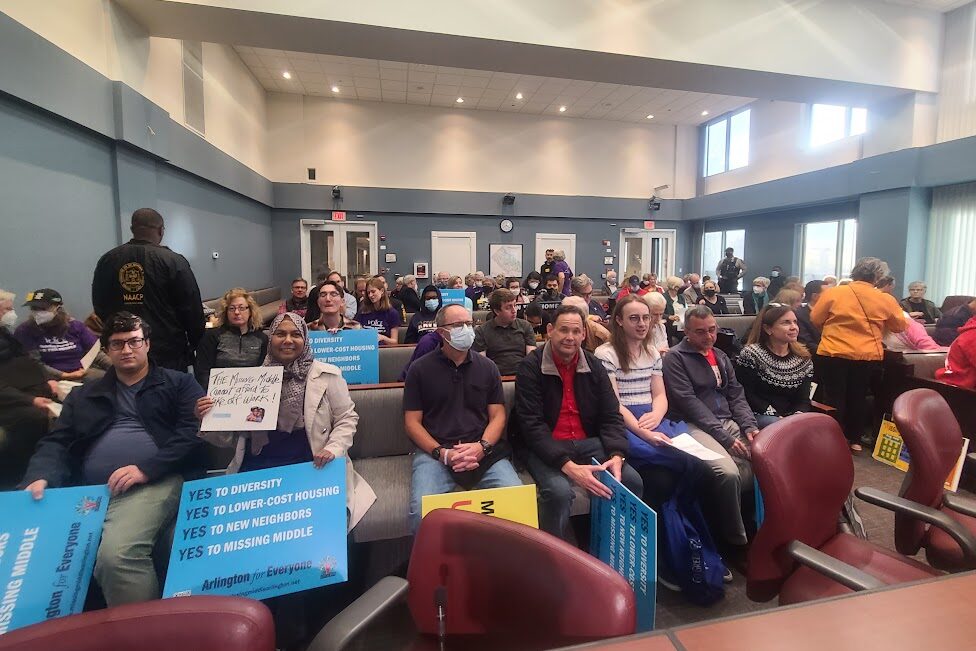

Gooden, who shared her anecdote during a county-facilitated conversation on the Missing Middle housing study, said in an interview with ARLnow that she is glad she could help her kids stay in Arlington if they wanted. She said she wants teachers, firefighters and nurses at the nearby Virginia Hospital Center to be able to afford to live here, too.

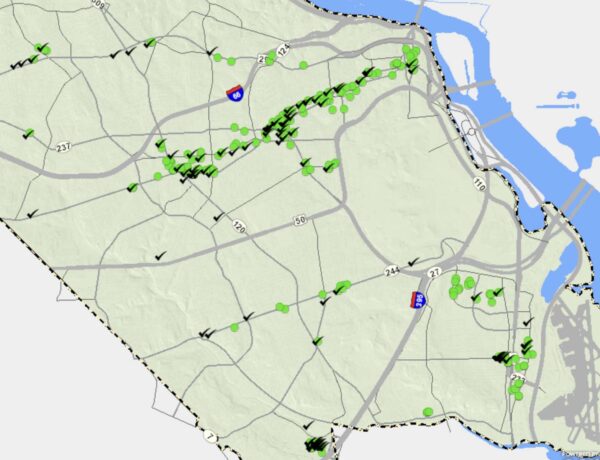

But all around her, new construction in Halls Hill is increasingly unaffordable — a new six-bedroom, single-family home with a modern design recently went for $1.7 million compared to a circa-1995, three-bedroom townhouse went for $825,000. Another new construction, single-family detached home on a dead-end street is listed for sale for $1.9 million.

There are still some relative bargains to be had in the neighborhood, like the five-bedroom rambler that sold for $735,000, but with each “fixer-upper” sale comes with the chance that another huge house from a local builder will replace it.

The pricier homes came at the expense of this historically Black community, Gooden said, as neighbors moved away for more space or cheaper property taxes and sold the property they inherited from their parents and grandparents.

“That completely changed that neighborhood,” Gooden said. “We don’t even know all our neighbors anymore. I used to know everybody.”

After all this upheaval, could the county’s plan to allow two- to eight-unit buildings in single-family neighborhoods create more attainable homeownership opportunities in Halls Hill? Could it prevent future displacement?

It’s unclear.

One prevailing attitude is “something is better than nothing,” but concerns remain that Missing Middle will increase development in Halls Hill without bringing down the price. Certain streets already allow low-density multifamily units, and given the recent sale of two duplexes for $1.2 million apiece, they’re worried new “middle housing” won’t be attainable and won’t stem the tide of gentrification.

“People who live here are worried Halls Hill will be targeted, not more north in Arlington, where options are needed,” said community leader Wilma Jones.

Some developers, meanwhile, are excited to tap into buyers who want homes that feed into Yorktown High School and still have lower property values, at least to compared to other North Arlington neighborhoods.

“There’s such little supply, people want to be anywhere in North Arlington,” said Charles Taylor, the head of acquisitions for Arlington-based Classic Cottages. “It’s pretty schools driven. A lot of times, we don’t granularly pick and choose ‘We want to be in this block or that block,’ it’s like, ‘Hey, this is a lot in North Arlington, it feeds into Yorktown, let’s go there.'”