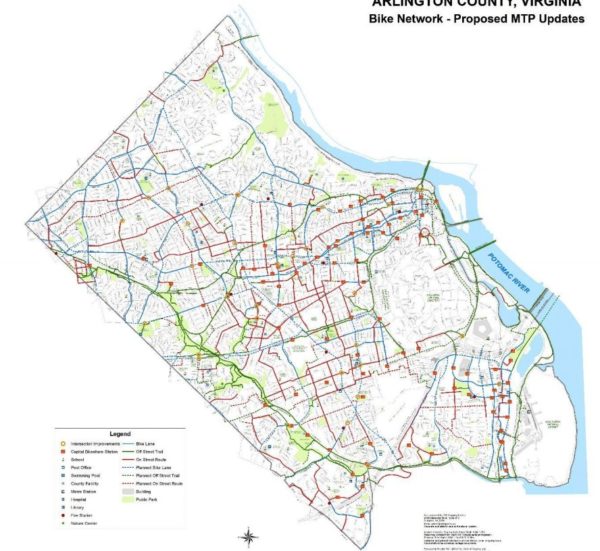

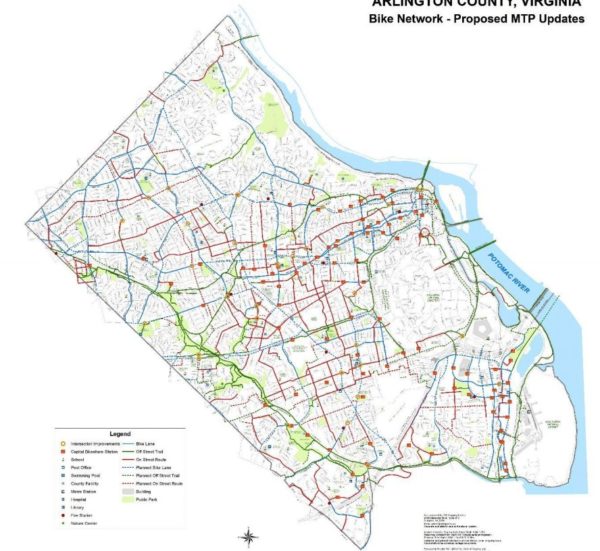

Arlington transportation planners’ latest attempt at crafting the future of the county’s cycling infrastructure has left neighbors, bicyclists and environmental advocates both pleased and disappointed.

The first draft of the 5o-page document, known as the bicycle element of the county’s Master Transportation Plan, originally included 26 cycling infrastructure projects including new trails and on-street bikeways. Since then, county staff has cut a few bike trails from the document, including two major projects: the Arlington Hall trail in Alcova Heights and another connecting the former Northern Virginia Community Hospital in Glencarlyn to Forest Hills, which were chopped after outcry from neighbors and environmentalists.

Still, bike advocates expressed broad support for the plan, but some think the latest draft doesn’t go far enough to ensure pedestrian safety and combat climate change.

“We made a number of changes in response to what we heard,” said Richard Viola, the project manager for updating the plan at the transportation division of the Department of Environmental Services (DES) told ARLnow Thursday. “I don’t think it negatively affects the overall plan, but it certainly shows a little more consideration of our natural resources.”

The plan is a sort of guiding “wish list” for the county, which some refer to as the “Master Bike Plan.” Viola’s group has been revising the document for more than a year, with the final version expected to be adopted later this spring. The latest edition will be posted publicly next week, he said.

During this latest revision, the county dropped its proposal for an off-street, half-mile trail connecting 6th Street S. to S. Quincy Street in the Alcova neighborhood at S. Oakland Street. The trail became a point of controversy because it could mean 6th Street residents lose some backyard privacy, and the county would cut down some important trees.

“We heard from a number of people from that Alcova Heights neighborhood that they did not want to see the trail built,” said Viola. “And then later we heard from a number of people in the neighborhood who want to see the trail build.” Ultimately, his working group shelved the Alcova trail idea for another time.

Another nixed idea was to extend the Four Mile Run Trail a half mile to connect with Claremont Elementary and Wakefield High. The Audubon Society wrote a letter in January warning that the proposal could cause “potential harm” to the rare magnolia ecosystem in the area.

“It’s a useful connection,” Viola said of the proposed trail. “People walk it today. But it would not be a suitable bike route when we thought about it because of the steepness [of the trail] and the proximity to this magnolia bog natural preserve.”

Another plan that became bogged down was a Glencarlyn/Hospital Trail connecting Glencarlyn and Forest Hills neighborhoods via the old site of the Northern Virginia Community Hospital. The half-mile project was envisioned by Viola’s team as a “low-stress route” between Arlington Boulevard and Columbia Pike because it could link up with other bikeways on S. Lexington Street, S. Carlin Springs Road, and 5th Road S.

The Audubon Society wrote that a trail passing through the old hospital site would “destroy valuable natural resources” in the conservation area that protects Long Branch Creek.

As a compromise, Viola’s team suggested instead widening the sidewalk on the east side of Carlyn Springs Road, so bikes and pedestrians can share.

“There are other comments they did not address in their plan,” said Audubon Society member Connie Ericson, referring to the organization’s January letter. “But we are pleased that they took some of our suggestions.”

However, members of the Arlington County Transportation Commission were “not wild” about the sidewalk idea, according to Commission Chair Chris Slatt.

Slatt told ARLnow Friday morning that members felt a paved, woodsy trail was too rare an opportunity pass up.

“There aren’t a lot of places where you could jog or bike without cars next to you,” he said. “It would seem like a shame to give up on that.”

In general, the plan drew praise from Ericson, and other advocates like D.C.-based Wash Cycle who said they couldn’t “spot any holes in the plans” in a January blog post.

Bruce Deming, who runs the Law Offices of Bruce S. Deming, Esq. and is known as the “Bicycle Lawyer,” also praised the Master Bike Plan for being “very thorough” and having a “cohesive strategy.” But he also told ARLnow in a phone call that, when it comes to safety, the “sense of urgency should be greater” in the latest draft.

The plan contains no mention of speed cameras — something Deming admitted is “politically unpopular” but reduces the injury and mortality rates in crashes with pedestrians and cyclists.

Deming also critiqued the plan for not prioritizing more bike lanes protected from cars, something 64 percent of respondents surveyed by the county wish for according to the Master Plan.

“According to the latest version of the plan, we’ve got 29 miles of bike lanes and 10 percent are the protected bike lanes,” said Deming. “I’d like to see that percentage increase substantially.”

Viola told ARLnow that the plan has been updated to language about “traffic safety education.”

The updates to Arlington’s Master Bike Plan are the first in 10 years, and according to Viola, the county doesn’t expect to undergo the process again for another decade. This comes a few months after the U.N.’s report indicating humans have 12 years to cut emissions before global warming causes permanent ecological damage, and reducing trips by car is one way to do this.

The Master Bike Plan acknowledges this, writing that improving the county’s pledges to improve air quality and reduce its emissions “depend greatly on shifting more travel to energy-efficient travel modes such as bicycling and walking.”

For Slatt, this means ensuring the infrastructure is so good it makes people want to ditch cars for bikes — something that would be easier to figure out how to do if the county allocated more resources and invested in high-end data analysis.

“People don’t people pick their transportation option because it saves the planet,” he said. “People pick their transportation option because it works for them because it’s faster or cheaper or makes them happy.”