Without in-person school, play dates and activities, many kids have lost their primary sources of social interaction and exercise due to COVID-19.

But volunteers in Arlington say a new traffic garden, a space where kids can play and learn how to travel roads safely, could restore some of the lost opportunities for play.

“It was clear we needed new stuff for kids to do,” said Fionnuala Quinn, who makes and consults on traffic gardens. “This is a friendly, happy place for them at a time when a lot has been taken away from them.”

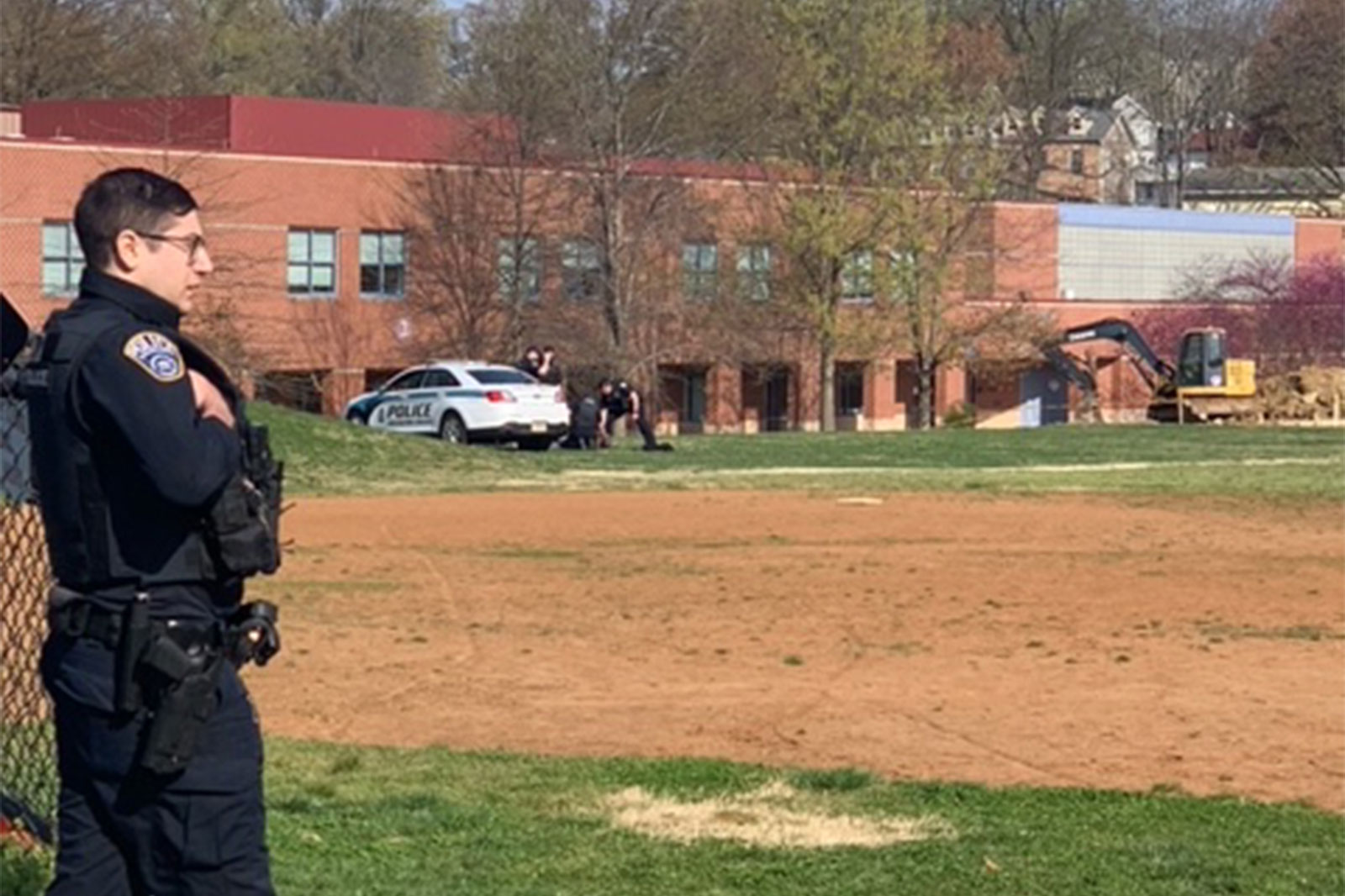

After getting approval from the Women’s Club of Arlington (700 S. Buchanan Street) in Barcroft to use their parking lot, a group of 10 bicycling enthusiasts, community members and engineers grabbed some chalk paint and duct tape and got to work. Three-and-a-half hours later, the parking lot was transformed into space with railroad crossings, crosswalks, streets and roundabouts that kids can walk, bike or skateboard along.

“It’s a bright spot in a tough time,” said Gillian Burgess, a cycling and walking advocate and former chair of the Arlington Bicycle Advisory Committee, who helped with the effort.

Families seem to enjoy it and kids find it intuitive, she said.

“It’s funny, parents will ask us how to use it, but kids just do it naturally,” she said.

The crew in Arlington is one of about 30 nationwide that have repurposed parking lots and constructed these temporary traffic gardens since the start of the pandemic, Quinn said.

“Once you start looking and thinking about this, you realize there is asphalt lying neglected everywhere,” she said. “As soon as you do it, small children appear.”

The original traffic gardens were built in the 1950s in Denmark and the Netherlands. They resembled miniature cities, with tiny buildings and kid-sized roads and traffic signs.

The trend made its way to the U.S., with a large concentration of them in Ohio, where they are called safety towns, Quinn said. She has catalogued about 300 installations in the U.S.

Quinn, who lives in Reston, left her engineering job to engineer and consult on traffic gardens full-time. She said the 50s-era gardens ertr amazing, but expensive to maintain and most kids only ended up going once during their childhood.

Her job is to make these gardens easier and cheaper to build and maintain so that they can be replicated on a smaller scale, more locally, and be more accessible to all kids.

She has helped with permanent installations at two Washington, D.C. schools, and spearheaded two in Alexandria and one in Fauquier County. They required months or years of planning and work.

But temporary pop-ups, including the one in Arlington, use little resources and take less time. Once people see how much kids love them, the pop-ups also advance the community conversation toward permanent versions, she said.

The Barcroft traffic garden will be in place for a few months. Burgess is working on getting the message out through schools and neighborhood email lists and has started looking for other locations in the county. She aims to add more gardens by this spring.

The group is working with the Arlington Safe Routes to School coordinator to apply for grants to fund permanent traffic gardens at Arlington schools.

With kids learning remotely, Safe Routes to School grants are going toward different educational initiatives, including traffic gardens, Burgess said. In the meantime, she and Safe Routes are also working with the school system to make walking and biking routes to school safer.

Photos courtesy Gillian Burgess