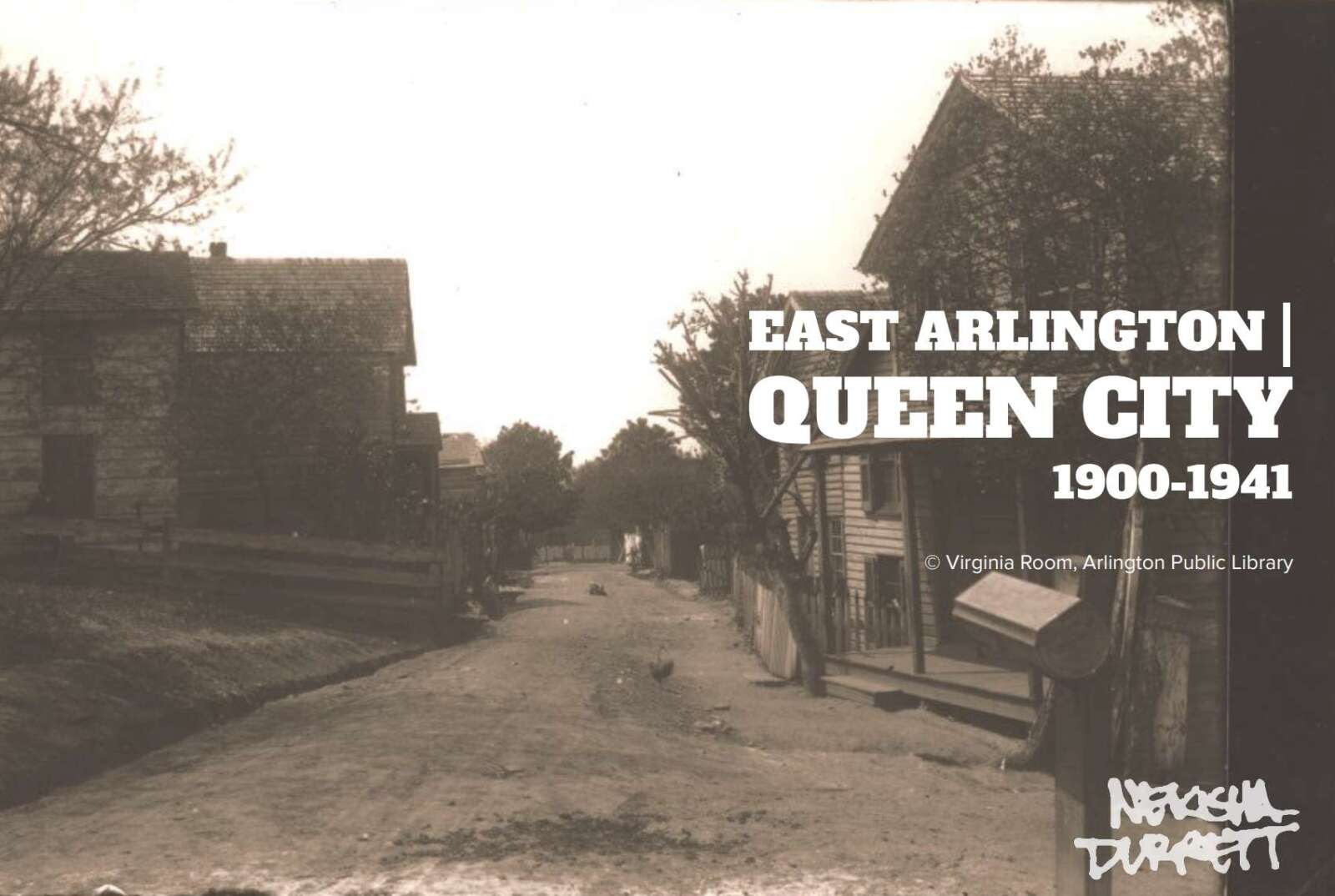

(Updated at 8:50 p.m.) A new historic marker has gone up at the 138-year-old Mount Salvation Baptist Cemetery, honoring the final resting place for a number of early Halls Hill leaders.

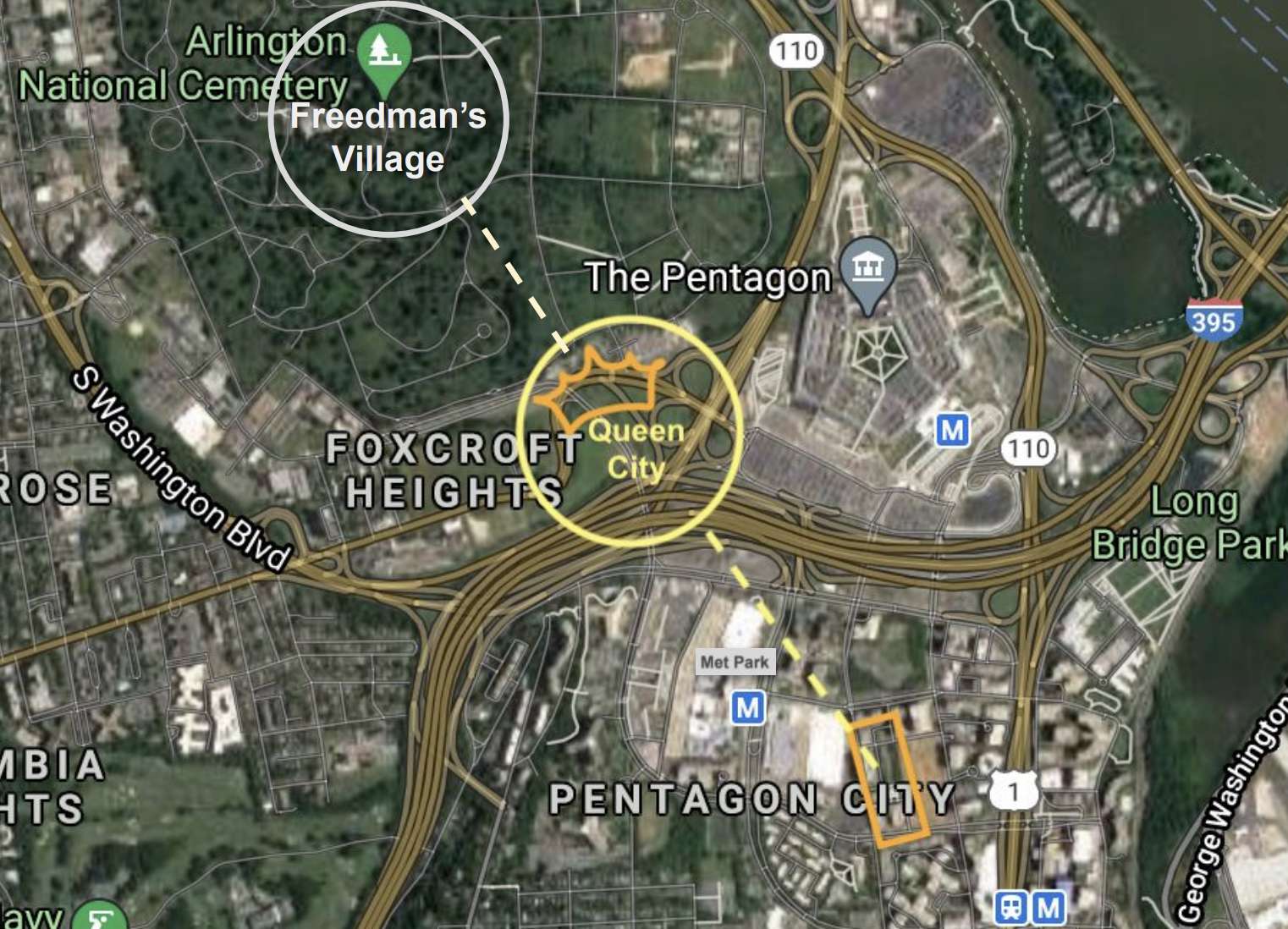

The county installed a historic marker in October at Mount Salvation Baptist Cemetery on N. Culpepper Street in the Halls Hill neighborhood, also known as High View Park. A brief unveiling ceremony was held in late November and attended by Board Chair Katie Cristol, local historian Charlie Clark, Black Heritage Museum president Scott Edwin Taylor, and others.

The marker reads:

“The Mt. Salvation Baptist Church trustees have maintained this cemetery since June 7, 1884 when they bought the property for $80. Reverend Cyrus Carter cultivated the congregation which began at the nearby home of Isabella Washington and Moses Pelham, Sr. The cemetery contains 89 known burials from 1916 to 1974, although earlier burials were likely.

This is the final resting place of many community leaders, including those who were formerly enslaved and their descendants. Members of this church provided stability and social support throughout segregation and served as a pillar of Arlington’s African American community. The cemetery became an Arlington Historic District in 2021.”

The cemetery was designated as a local historic district last year and the marker was approved by the county’s Historical Affairs and Landmark Review Board (HALRB) in April 2022.

“Being a Local Historic District (LHD) is not required to request a marker, but we thought this would be a wonderful opportunity to celebrate our newest LHD and provide a small glimpse into the history for those enjoying the neighborhood,” county historic preservation planner Serena Bolliger wrote ARLnow in an email.

The cemetery is the final resting place for at least nearly 90 early residents of Halls Hill, a fact known thanks to a ground-penetrating probing survey that was done in October 2019 with permission from the church. The probing also revealed potential grave markers and borders.

Buried at Mount Salvation are a number of influential Arlingtonians including Lucretia M. Lewis, Moses Pelham, and Annie and Robert Spriggs.

Scott Edwin Taylor, president of the Black Heritage Museum of Arlington, told ARLnow that what also makes Mount Salvation special is that it’s a great example of how traditional African American cemeteries were laid out and designed prior to the turn of the 20th century. Graves are often oriented east to west, with the head point westward. Burial plots tend to be shallow, no deeper than four feet, with plantings.

“Some anthropologists have suggested that marking graves with plants may have been rooted in the African belief in the living spirit,” reads the county’s report on the cemetery.

Some graves even have seashells.

“A lot of Black Americans, before the turn of the [20th] century, used seashells. It was… like asking angels to watch over the graves. A couple of the graves still have those seashells on there,” Taylor said.

Mount Salvation is one of two still-remaining, church-affiliated, historic African-American cemeteries in the Halls Hill neighborhood with the other being Calloway Cemetery on Langston Blvd.

It’s important to preserve these sites for generations to come, Taylor explained.

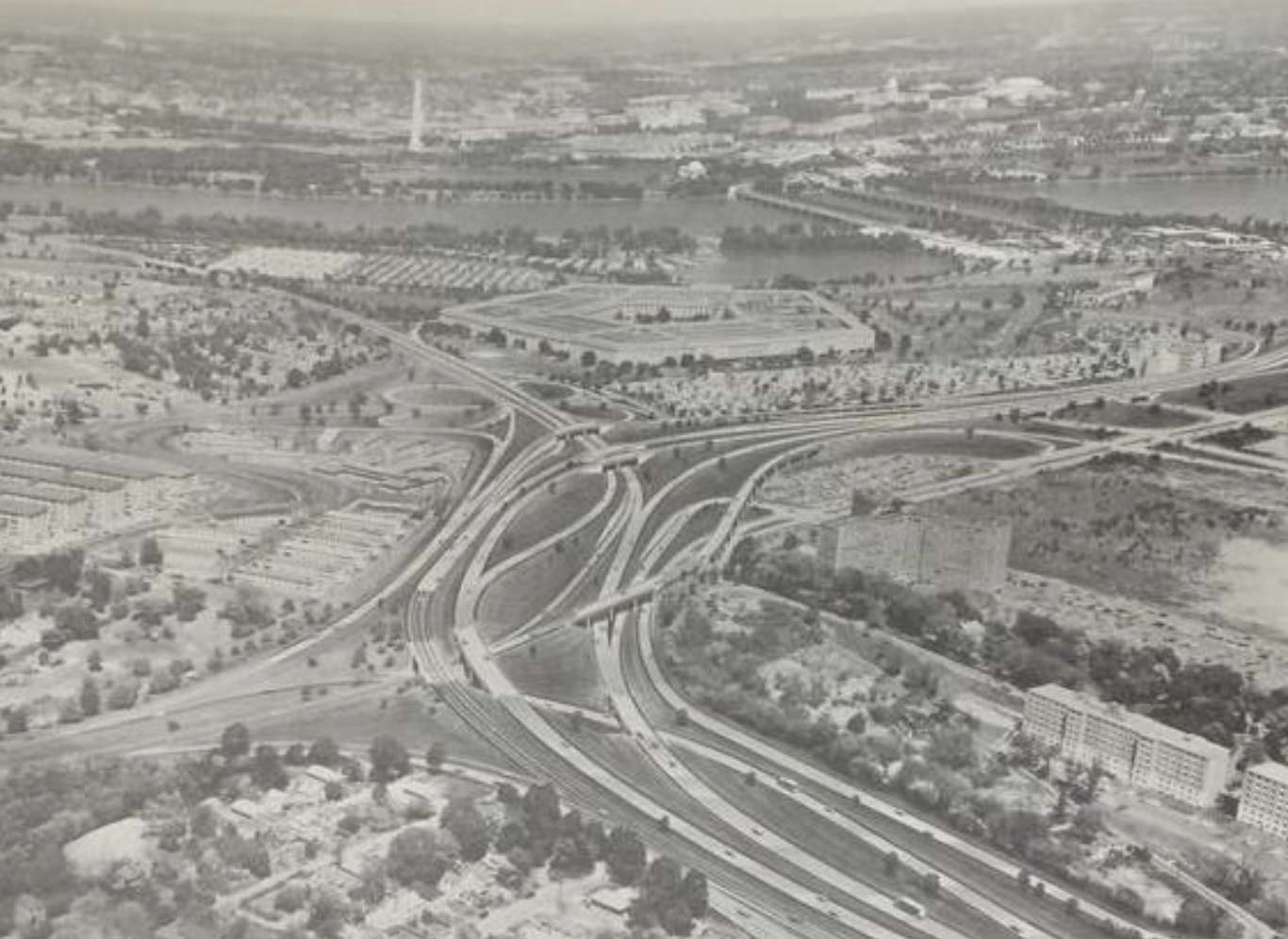

“The gentrification that’s going on in Arlington is moving at the speed of light,” Taylor said. “When we have landmarks like [this], we need to cherish them because it shows the real African-American experience.”