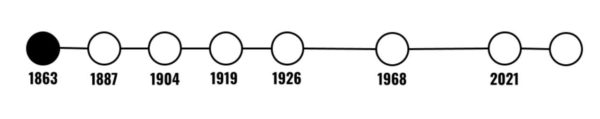

This is set to be a pivotal year for how Arlington County represents itself in its logo and its infrastructure.

At the close of 2020, Arlington County kickstarted the process of updating its logo — a process that will soon be inviting public input — and this fall, County Board members expect to review a new framework for considering the possibility of new names for things like parks, streets and building.

Board member Christian Dorsey and NAACP President Julius “JD” Spain, Sr. previewed these upcoming changes during a recent discussion on renaming hosted by the Arlington Committee of 100, a group that talks about local issues.

Meanwhile, Marymount University assistant professor Cassandra Good shed light on the history of Arlington’s street naming and made recommendations for a new approach.

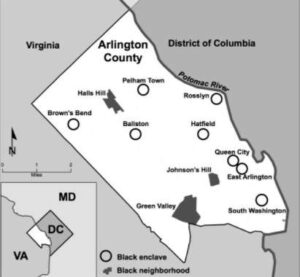

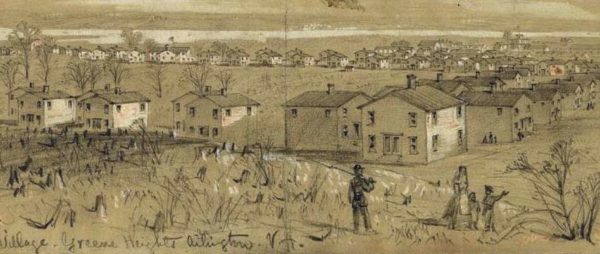

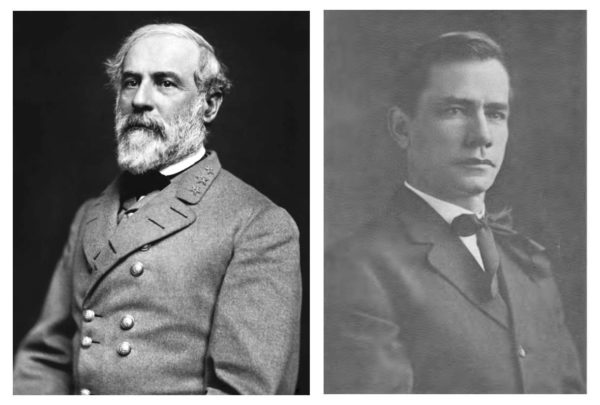

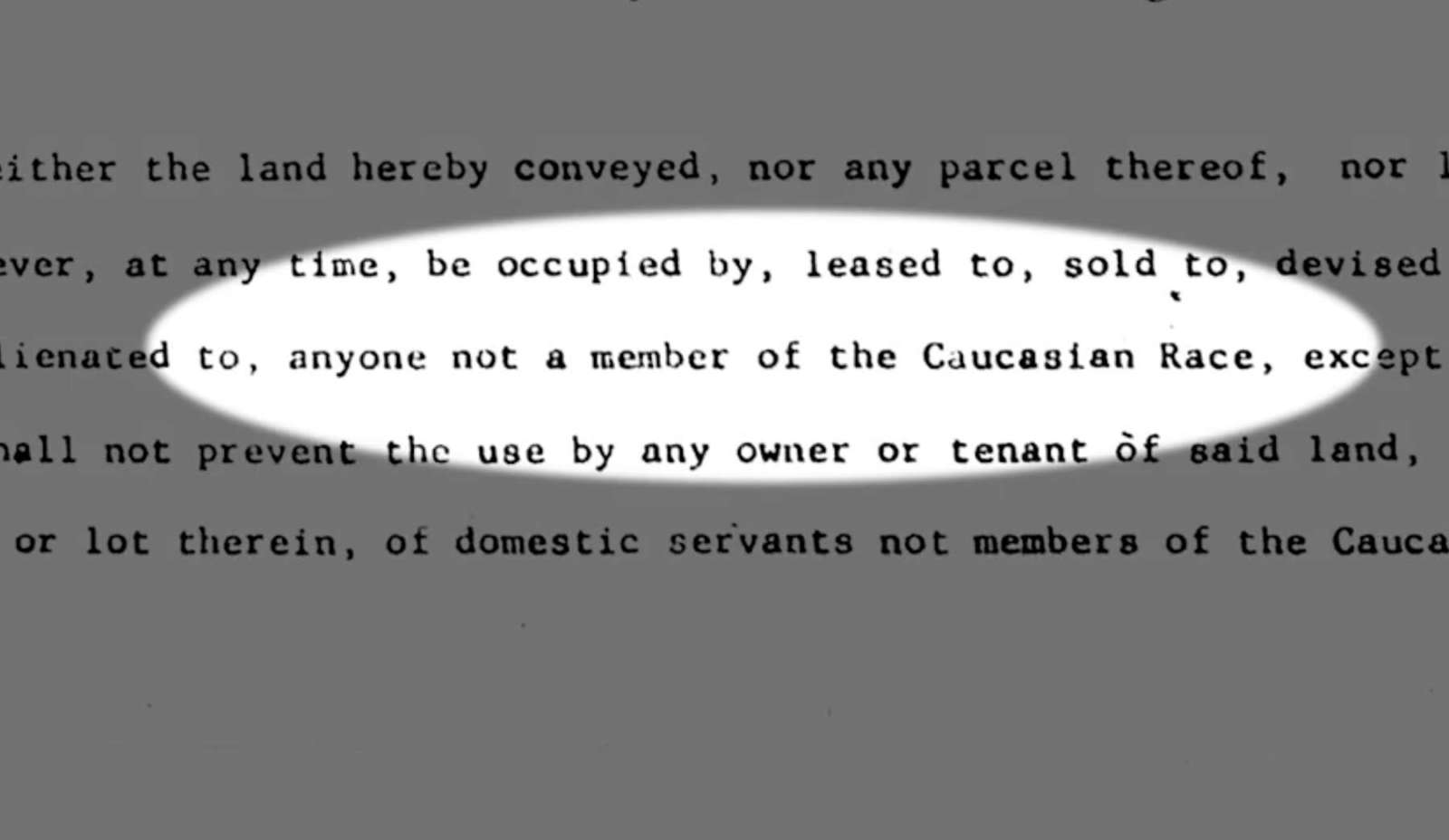

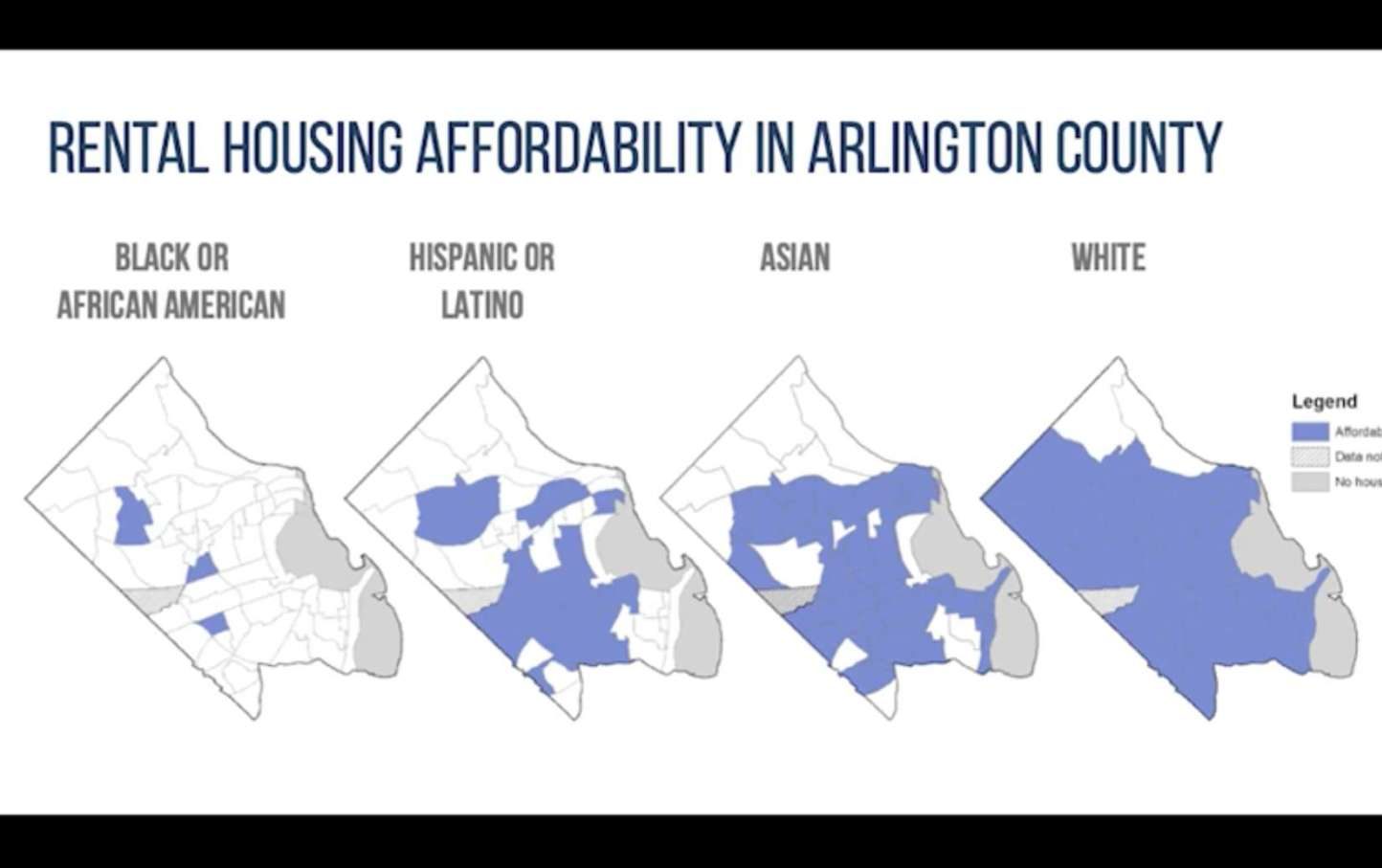

Spurred by a national discussion of systemic racism and police violence in 2019 and 2020, Arlington County is re-examining its logo, which depicts Arlington House: The Robert E. Lee Memorial, the former plantation home of the Confederate general and descendants of George Washington. The county is also reconsidering the names of various roads, parks and local landmarks named for Confederate generals and soldiers, slaveholders, plantations, and historic figures known for their racism.

That work is ongoing. A county logo review panel has received more than 250 submissions to consider and narrow down to five for the community to rank in May, Spain said. The County Board will select a new logo in June.

Meanwhile, county staff members are hammering out a formal process for naming and renaming places in Arlington going forward, to bring a systematic approach to what has so far been a case-by-case process.

“We expect that during the fall of this year, we will have a proposal from our county manager for how we ought to think about the renaming issue,” Dorsey said. “There’s going to be a lot more that comes with that, I expect.”

Some Committee of 100 members wondered whether the panelists think the county ought to change its name, too, given that the county is named after the plantation house that’s being removed from the logo.

Panelists said such a conversation could take place but changing the name Arlington would not only pose an extreme logistical challenge but may also not reflect a nuanced view of renaming.

“When we’re talking about changing the name of Arlington, it may come a time when we need to have that conversation,” Spain said. “But Arlington — I believe changing the name of a county is a pretty heavy lift.”

Dorsey said he is not in favor of throwing out everything that was the product of a certain time in history as “the poisonous fruit of a poisonous tree.”

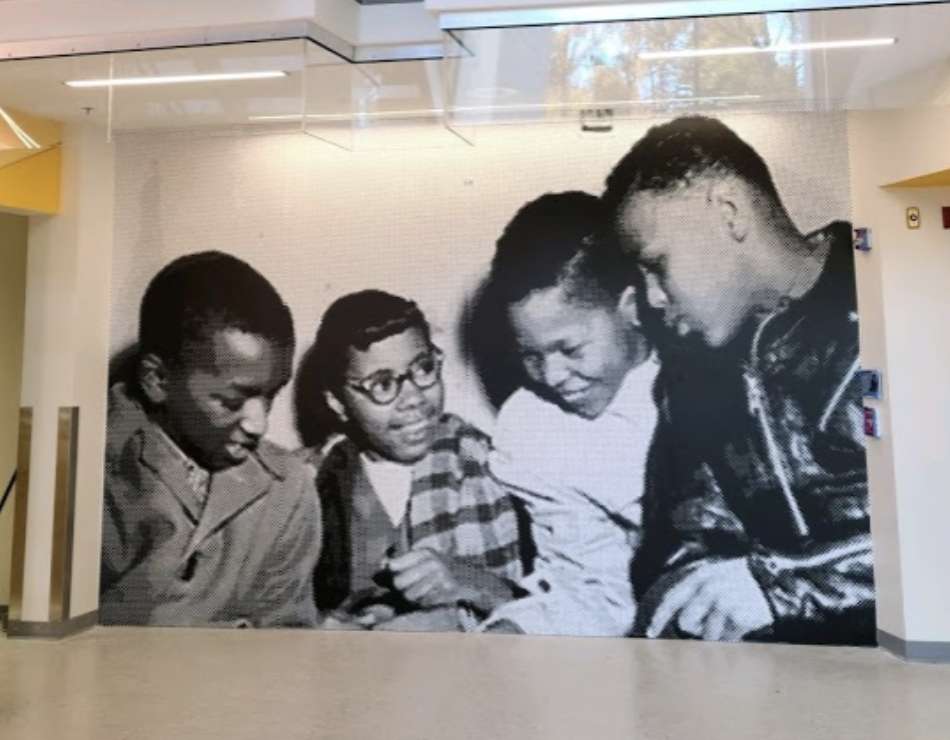

A recurring question for officials tasked with renaming has been whether to swap one historical figure with another. The community could choose a person whose character could come into question later on, they said.

Good, the Marymount professor, said while her preference is not to use names of historical figures, there ought to be a few new historical figures featured.

“There need to be some names for people,” she said, otherwise, “the names that remain will mostly white people.”

Dorsey added that while the county can think beyond individuals, there will be some figures who community members will want to honor.

“I would hate to lose that entirely,” he said.

Good said Arlington first formalized a naming process for streets in 1932, when a commission of, as far as she can tell, all-white Arlington residents finalized the names for the county’s streets. Several — including Lafayette, Hamilton and Pocahontas Streets — were renamed at that time, she said.

Going forward, she recommended that all renaming decisions include those who have been excluded and involve a professional historian. Renaming should be considered if the current name was originally chosen to honor somebody for reasons that are at odds with the community’s values, she said.