Arlington County historians are collecting artifacts to document the history of the Latino community in the county.

So far, some notable contributions include personal effects from former Arlington School Board member Emma Violand-Sanchez, who has been active in the Latino community for many years, Arlington Center for Local History Manager Judith Knudsen tells ARLnow.

“She is a wonderful resource and has also introduced us to several organizations [and] people who also have material we would like to receive and preserve,” Knudsen said. “The Bolivian Soccer League has donated their records and Kathie Panfil who worked in the schools for many years has also donated material.”

Between 1990 and 2000, Arlington’s population of Hispanic and Latino residents increased by nearly 53% and today, this group makes up 15.7% of the population, according to the Center for Local History, or CLH. But the Arlington Community Archives stewarded by the CLH did not grow at the same rate.

To remedy that, county archivists embarked on this multi-year collecting initiative, dubbed “REAL,” or el Re-Encuentro de Arlington Latinos. The CLH is looking to fill the holes in its archives with donated materials from people, businesses, civic groups, schools and the government documenting the history of Arlington’s Latino community.

“Community archives play a vital role in documenting all voices of a community,” the library website says. “Understanding the diverse experiences of these individuals, students, families, businesses, officials and community groups is critical to understanding Arlington’s history. With four decades of rich community history, it is vital to begin collecting materials that capture this story.”

Efforts like this take time, Knudsen says, adding that REAL has always been seen as a long-term project.

“Current organizations are busy working to help their communities, understandably, and donating material to an archive is not the first thing on their mind,” she said. “However, as more groups donate the word spreads and we get more donations. We just have to be patient and remind organizations/individuals from time to time. The interest is there.”

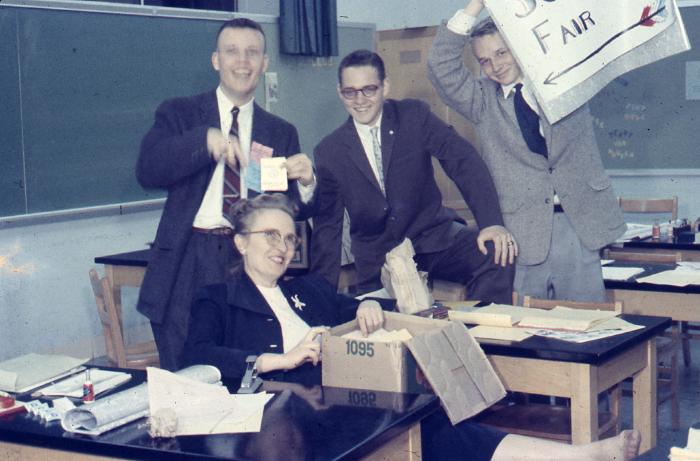

The CLH is accepting any and all materials “created in the process of engaging in community, civic, educational or personal pursuits in Arlington County.”

Examples include:

- Meeting Minutes or notes

- Fliers

- Financial Materials

- Publications

- Photographs

- Newsletters

- Personal Papers such as diaries, journals, notes, lists, etc.

“Donated materials will become part of the Center for Local History’s Arlington Community Archives, and will be available to donors and other researchers,” the website says. “Donations may be digitized to increase access.”