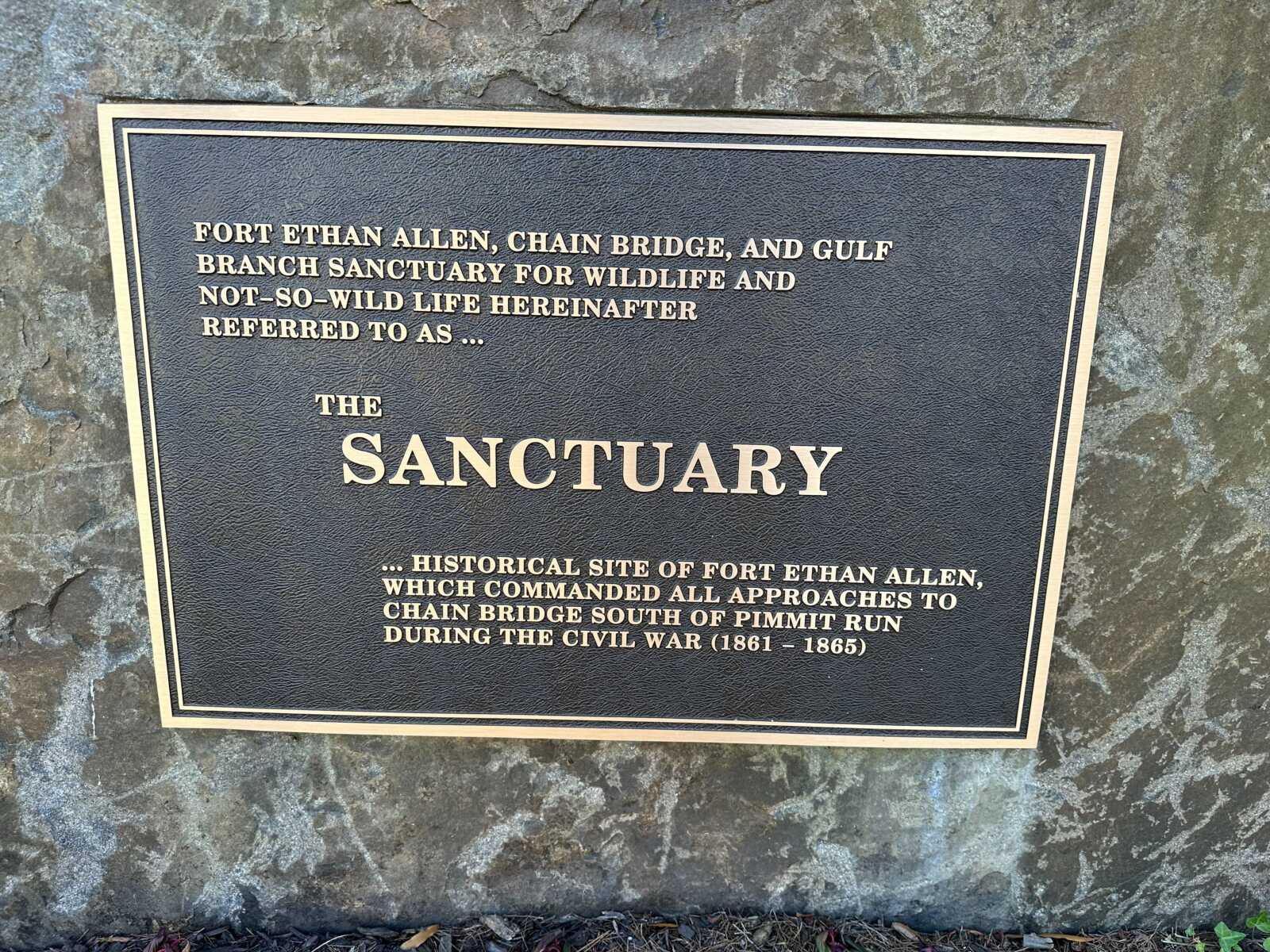

A curious plaque outside a private development in the Old Glebe neighborhood underwent some copy-editing in recent years.

The plaque is attached to a large stone on the corner of N. Richmond and Stafford streets, near where Fort Ethan Allen once stood. It marks the entrance to a development across the street from the Madison Community Center and Fort Ethan Allen Park, built by former developer and prominent philanthropist Preston Caruthers, who died earlier this year.

For years, it sported the following inscription, complete with a cheeky but outdated reference to the Civil War.

FORT ETHAN ALLEN CHAIN BRIDGE GULF BRANCH SANCTUARY FOR WILDLIFE AND NOT SO WILDLIFE HEREINAFTER REFERRED TO AS …

THE SANCTUARY

… HISTORICAL SITE OF CIVIL WAR FORT ETHAN ALLEN WHICH COMMANDED ALL THE APPROACHES SOUTH OF PIMMIT RUN TO CHAIN BRIDGE DURING THE WAR OF NORTHERN AGGRESSION (1861-1865)

Coined by segregationists during the Jim Crow era, “The War of Northern Aggression” is decidedly not the preferred nomenclature for modern Arlington sensibilities.

Finally, in 2020 — a year that saw significant upheaval locally amid a national racial reckoning after the murder of George Floyd — “The Sanctuary” got a new plaque.

Preston’s son, Stephen Caruthers, says the homeowners association spent $5,000 to change the sign and leave out the ‘War of Northern Aggression’ reference. One resident, who has since moved away, was “the primary mover and shaker responsible for suggesting that be changed.”

“It was agreed upon by the members here and that’s the entire story,” Caruthers said.

“When my dad wrote that, some of it was tongue-in-cheek,” he continued. “If you read the entire description, he made light of the fact that ‘the Sanctuary’ is for the wildlife and the not-so-wildlife, referring to the residents who live there.”

Still, the younger Caruthers acknowledged that many people were upset by the term, which he says he understands.

Resident John Belz says the plaque aggravated him the first time he saw it and whenever he would think about it afterward. It was his wife who noticed the plaque had changed when she was volunteering as a greeter during early voting this year.

“I’m glad they changed it,” he wrote.

“I recognize that Virginia was part of the Confederacy, but it surprised (shocked?) me that more than 100 years later, someone in this area would refer to the rebellion as ‘The War of Northern Aggression,'” Belz continued. “And plant a sign, which refers to the Union fort that was there, within yards of the place.”

Stephen emphasized that his father, who died at the start of 2023, has a more enduring legacy than this plaque as “Mr. Arlington.”

Preston Caruthers was a prolific donor who contributed land to Arlington County and made financial contributions to the Virginia Hospital Center Foundation, Marymount University, Shenandoah University, and the David M. Brown Planetarium, among other institutions.

“My dad was very involved in many things here in Arlington,” his son Stephen said. “He had a very full life, he loved Arlington, and was always trying to do things to help Arlington.”