Arlington County is slated to accept a $95,000 grant to place two older adults with serious mental illnesses in community-based treatment once they leave state psychiatric hospitals.

The money will pay for housing costs, medications, transportation, or other associated costs as part of their treatment plans.

Their discharge, treatment and funding plans are approved by Arlington’s Community Services Board. These county-appointed community members oversee how the county Dept. of Human Services provides services to people with mental health challenges, developmental disabilities and substance use disorder.

The one-time grant funds come from the Virginia Dept. of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services. Not having this grant would mean longer wait times for these two individuals set to leave a state hospital, says DHS spokesman Kurt Larrick.

“If we did not have this funding available right now, they would need to wait until a slot in the [Regional Older Adults Facility Mental Health Support Team (RAFT) program] became available or clinical staff identified another option,” Larrick said.

RAFT is a grant-funded program that discharges older adults from psychiatric hospitals to long-term care and, where possible, diverts them from hospitals in the first place. Arlington County DHS manages it for Northern Virginia, says Larrick, and partners with assisted living and nursing home facilities throughout the region.

The 10-person team works to provide community treatment options to people ages 65 and older who have a diagnosis of serious mental illness or dementia and who either have been hospitalized in a psychiatric facility or are at risk of hospitalization.

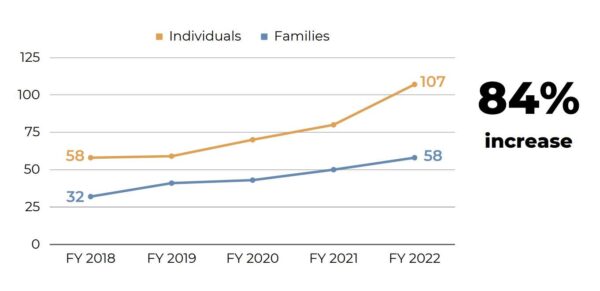

It served 106 clients last fiscal year, up from 73 the year prior, a 45% increase attributed to the launch of a dementia program in January 2023. Through this program, the team helps ensure people with dementia can live at home or with a caregiver by providing specialized dementia training to caregivers.

The team also provides on-call support to assisted living and nursing home facilities to prevent psychiatric hospitalizations or oversee discharge when a client is hospitalized.

RAFT has a 90% satisfaction rate among clients and partnering organizations, according to a recent survey, in which several people shared their gratitude for the program and its staff.

Each year, RAFT receives $500,000 from DBHDS. While the program faces budget pressures, due to factors such as inflation, Larrick says running the program remains tenable.

Individuals who receive treatment through RAFT are asked to contribute what they can to their care, he said. To keep costs down, the program also leverages community partnerships and other resources for older adults.