Ed Talk is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

Ed Talk is a biweekly opinion column. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

The school-to-prison is the most misunderstood phenomenon in Arlington, even amongst the highest levels of leadership. School board and county officials, including law enforcement and the former Commonwealth Attorney, have vehemently denied that the school-to-prison pipeline exists in Arlington.

They acknowledge the phenomenon but contend that it exists elsewhere, but “not here.” Such narrow-mindedness is troubling. Perhaps it is cognitive dissonance that causes them to recoil at the mere suggestion that our affluent county with its highly educated residents and top-ranked schools is complicit in the school-to-prison pipeline. It is.

The naysayers misunderstand the pipeline to prison as a linear path on a monopoly board: Go directly to jail; do not pass go, do not collect $200. In fact, the School-to-Prison Pipeline is a tapestry of school policies and procedures that drive many of our children into a pathway that begins in school, and after many bumps, twists, turns and detours, ends in the criminal justice system. Simply put, the pathway from school to prison is multifaceted and often indirect. While there are many pathways, I discuss the three that most frequently intersect and overlap. Each is broken in APS.

Illiteracy

There is enough research to show a direct correlation between a person’s future success rates and the likelihood of them becoming involved in the criminal justice system, due to their literacy levels. Research shows that children who struggle to read in first grade are 88% more likely to struggle in grade four; and those who struggle in fourth grade are four times more likely to drop out of school. Data reveals that 85% of juveniles who interact with the court system are functionally illiterate, and 60% of the nation’s inmates are illiterate. While it is an urban myth that prisons base some of their future planning on third and fourth-grade literacy rates, the data is compelling that there is a strong connection between early low literacy skills and incarceration rates.

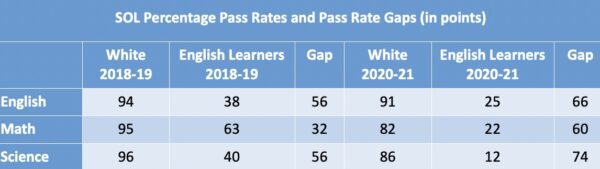

In our own yard, the pandemic has exacerbated the declines in reading proficiency. APS spent decades attempting to teach students to read using balanced literacy instead of structured literacy, which has not worked well. As a result, we have students who are graduating functionally illiterate, if at all. This is known as failing up. The recent planned scale-up to structured literacy is slow and focused primarily on K-3, leaving students in the upper grades and secondary schools without a clear and solid path for evidence-based reading intervention.

Special Education

Students with disabilities who qualify for special education too often receive inferior services, and often in segregated settings, if they receive any services at all. The proverbial wait-to-fail practice of delaying evaluations precludes early identification of learning disabilities and compound intervention.

The APS 2019 Special Education Evaluation indicates that more than one-third of students with Individual Education Plans reported that only some or none of their teachers have high expectations for them, and that they do not feel understood or supported by their teachers. One-third reported not being able to participate in after-school activities, not being treated fairly, and not feeling welcomed in school.

Disparate discipline and disproportionate referrals to law enforcement

The discipline disparities we see in APS are reflective of the national data that Black students are suspended, expelled and reported to law enforcement three times more than White students. Many of them have learning disabilities and/or trauma, and would benefit from additional educational and counseling services. Instead, they are isolated, punished and pushed out. Students who have difficulty learning to read will often act out in school. Additionally, Black students tend to receive harsher punishment for less serious behavior, and are more often punished for subjective offenses, such as “loitering” or “disrespect.”

The U.S. Department of Education, reports that students with disabilities incur repeated disciplinary actions and are more than twice as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension than students without disabilities. Students with disabilities represent 12% of the overall student population, yet make up 25% of all students involved in a school-related arrest. (Similarly, LGBTQ youth are much more likely than their heterosexual peers to be suspended or expelled.) Because disparate discipline impacts students of color with disabilities, dismantling the Pipeline requires an intersectional approach to disability and racial discrimination.

Notwithstanding the School Board’s removal of School Resource Officers (SROs) from APS pursuant to recommendations from the SRO Work Group and Superintendent Francisco Durán, Governor-elect Glenn Younkin has threatened to withhold funding from school districts that don’t have SROs, which he’s said he will require. Regardless of whether SROs actually return to APS, discipline disparities and referrals to law enforcement will continue unabated unless school administrators, who overwhelmingly favor having SROs in their schools, evolve to embrace restorative practices. That would require a seismic shift in mindset and culture.

In a regressive legislative move, a Republican-sponsored bill (SB2) has already been pre-filed for the 2022 General Assembly session to revive a mandate that school administrators report misdemeanors to law enforcement. Less than a year ago, SB 3/HB 256 was enacted as a specific antidote to the school-to-prison pipeline, for which Virginia ranks as one of the worst states.

Given the trauma experienced by children during the pandemic, experts anticipated unprecedented behavioral difficulties and pervasive attendance problems in the reopening of schools. Phyllis Jordan of Georgetown University’s FutureEd opined that:

“[T]here are going to be kids who have behavioral outbursts, and you’re just going to have kids who are out of practice at being in school who are just not behaving properly. And the worst thing a school can do is flush them all out with suspensions or harsh discipline. There is going to have to be some attention and training on issues like restorative practices and ways of coping with these issues that kids are going to have.”

Conclusion

Illiteracy, special education and discipline are major pathways in the school pipeline to prison, but racial bias is the express route. Confronting racial bias is where the hard work is, and where I find that some Arlington leaders are unwilling to toil. If they would stop gaslighting us by denying the school-to-prison pipeline exists here, that would be a start. Stop. Listen. Learn. We can’t change what we won’t acknowledge.

Symone Walker is a federal attorney and an APS parent. She serves as Vice Chair of the Arlington Special Education Advisory Committee (ASEAC), and is an Executive Committee Member of the Arlington NAACP and Co-Chair of the NAACP Education Committee. Symone is a former candidate for the Arlington school board.