(Updated at 9:55 a.m.) The Arlington County Board has done away with parking restrictions on a handful of streets in two South Arlington neighborhoods, putting to rest a contentious dispute that has dragged on for years between Forest Glen and Arlington Mill residents.

The Board voted unanimously Saturday (Jan. 26) to end zoned parking on eight streets in the area. As part of the county’s “Residential Parking Program,” the county previously barred anyone without a permit from parking on the roads from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m. each day.

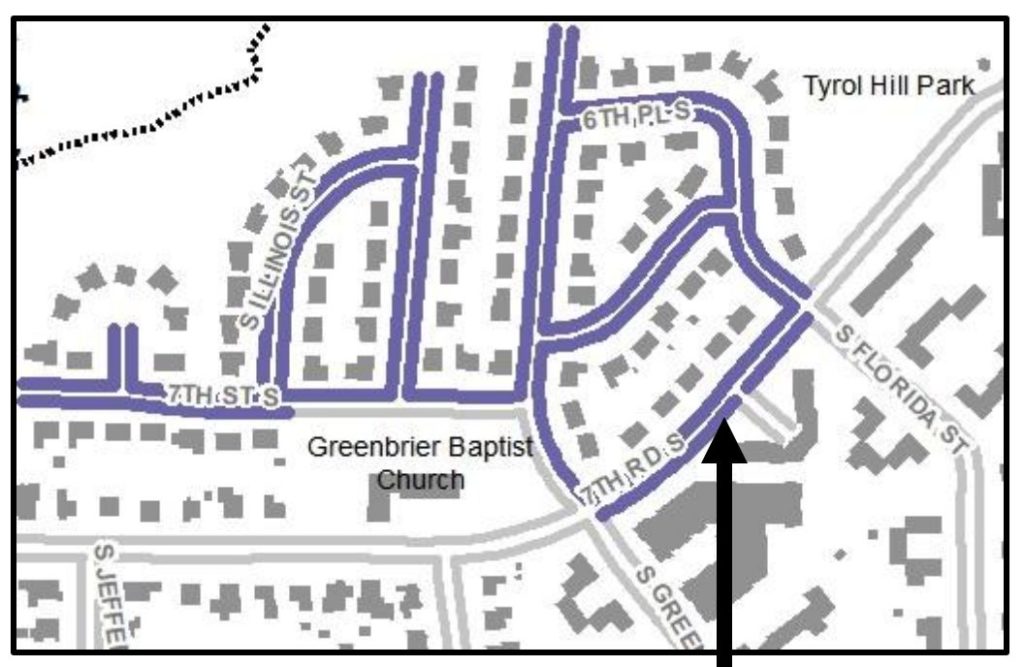

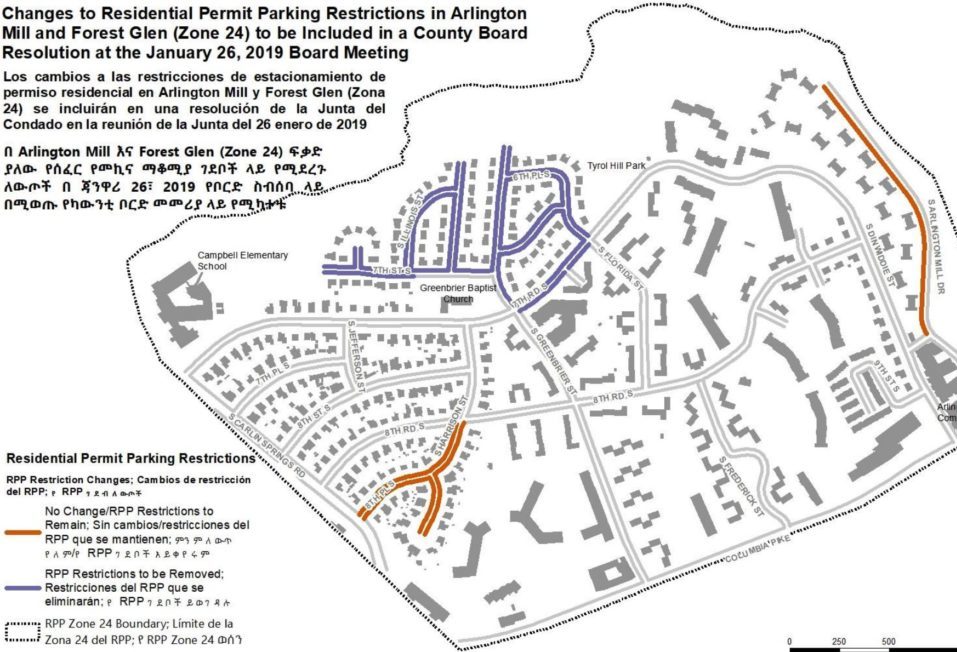

The following streets, once part of the county’s “Zone 24” and stretching into sections of both Forest Glen and Arlington Mill, are now open for parking around the clock:

- 6th Place S.

- 7th Street S.

- 7th Road S.

- S. Florida Street

- S. Greenbrier Street

- S. Harrison Street (north of 7th Street S.)

- S. Illinois Street

- S. Jefferson Street

Arlington officials first zoned the streets off in 2016, largely due to Forest Glen residents arguing that too many drivers from outside the area were occupying the neighborhood’s limited parking spots. But residents of Arlington Mill said they started to feel the squeeze instead once that change was made, as it cut off street parking near the many apartment complexes in the neighborhood.

“Street parking in Arlington Mill became so scarce that it was rare to find a parking spot anywhere after 7 p.m.,” Austin McNair, an Arlington Mill resident who fought for the change, told ARLnow via email. “Anyone not working a traditional 9 to 5 job was now faced with the extra task of finding parking more than a mile away from their home. I can promise that this is the story for many families.”

Ordinarily, the county likely wouldn’t have waded into such a dispute — the Board put a two-year moratorium on any parking zone changes as it reviews the efficacy of the entire program, a process that isn’t set to wrap up until sometime early next year.

Yet the Board subsequently determined that county staff didn’t follow their usual process for setting up the zoned parking in the area, convincing officials that the parking restrictions both weren’t working well and that they were likely set up improperly in the first place.

“This was not a decision that we take lightly or came to easily… but the status quo is not acceptable,” said Board member Erik Gutshall. “What this is all about, for me, is the efficient allocation of a public resource, which is on-street parking. I’m sorry that this is the least objectionable of lots of other bad options.”

Board members stressed that they’d urged staff to work out some sort of compromise position between the two neighborhoods over the past few months, perhaps by putting restrictions on one side of each street but freeing up the other side. But they could never quite find an acceptable solution to all sides, or manage to find one that county lawyers thought would hold up in court — the county’s parking restrictions were challenged all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1977, and officials have since been careful to limit the parking zones to the narrow intent of keeping commuters out of residential areas.

“While the neighborhood has grown in density, it has never been and is still not a destination for commercial customers or commuters who would be parking their cars to access public transportation,” McNair said.

The dispute has also turned a bit ugly in recent weeks. A community meeting the Board convened to discuss the matter drew plenty of raised voices, with some in Forest Glen arguing that the parking restrictions were necessary to prevent speeding, littering and other criminal activity in the neighborhood. Others in Arlington Mill, particularly some advocates for Latino residents, claimed those concerns were based in some deep-seated racial stereotypes.

That divide was evident at the Board’s gathering as well. Danny Cendejas, an activist on variety of local issues, told the Board that the current parking restriction “has discriminated against our neighbors,” while Forest Glen residents argued that reversing the restriction would harm their quality of life.

“I had to place trash cans in the middle of the street to slow down people who were racing to find parking while my three young children were riding their bicycles,” Brent Newton, a six-year resident of the neighborhood, told the Board. “When we were granted the [Residential Parking Program designation], our neighborhood became quiet, clean and tranquil. With utmost certainty, it will return to what it was before the RPP: speeding cars, trash and noise.”

While Board members sympathized with those concerns, they didn’t believe changing the parking restriction would make a difference on those fronts. Board member Libby Garvey suggested that they may be “related,” but she would rather see police step up enforcement in the area to address those worries.

Gutshall pointed out that his own neighborhood, near Clarendon, has parking restrictions in place, but still deals with its own share of littering issues as people flock to the area to reach nearby bars and restaurants. For him, and the rest of the Board, the parking staff’s missteps in evaluating the neighborhood for earning zone restrictions were more important to address.

Stephen Crim, the manager of the county’s parking program, told the Board that his staff discovered that they didn’t check license plates on the affected streets against records maintained by the county’s Commissioner of the Revenue, which tracks tax payments on property like vehicles. That means that staff didn’t necessarily have a full picture of how many people from outside the county were actually parking in the neighborhoods.