Lyon’s Legacy is a limited-run opinion column on the history of housing in Arlington. The views expressed are solely the author’s.

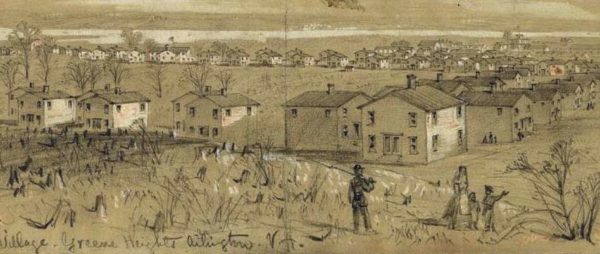

Arlington County was once home to a community of former slaves so prosperous that tours were given to foreign dignitaries as evidence of America’s racial progress.

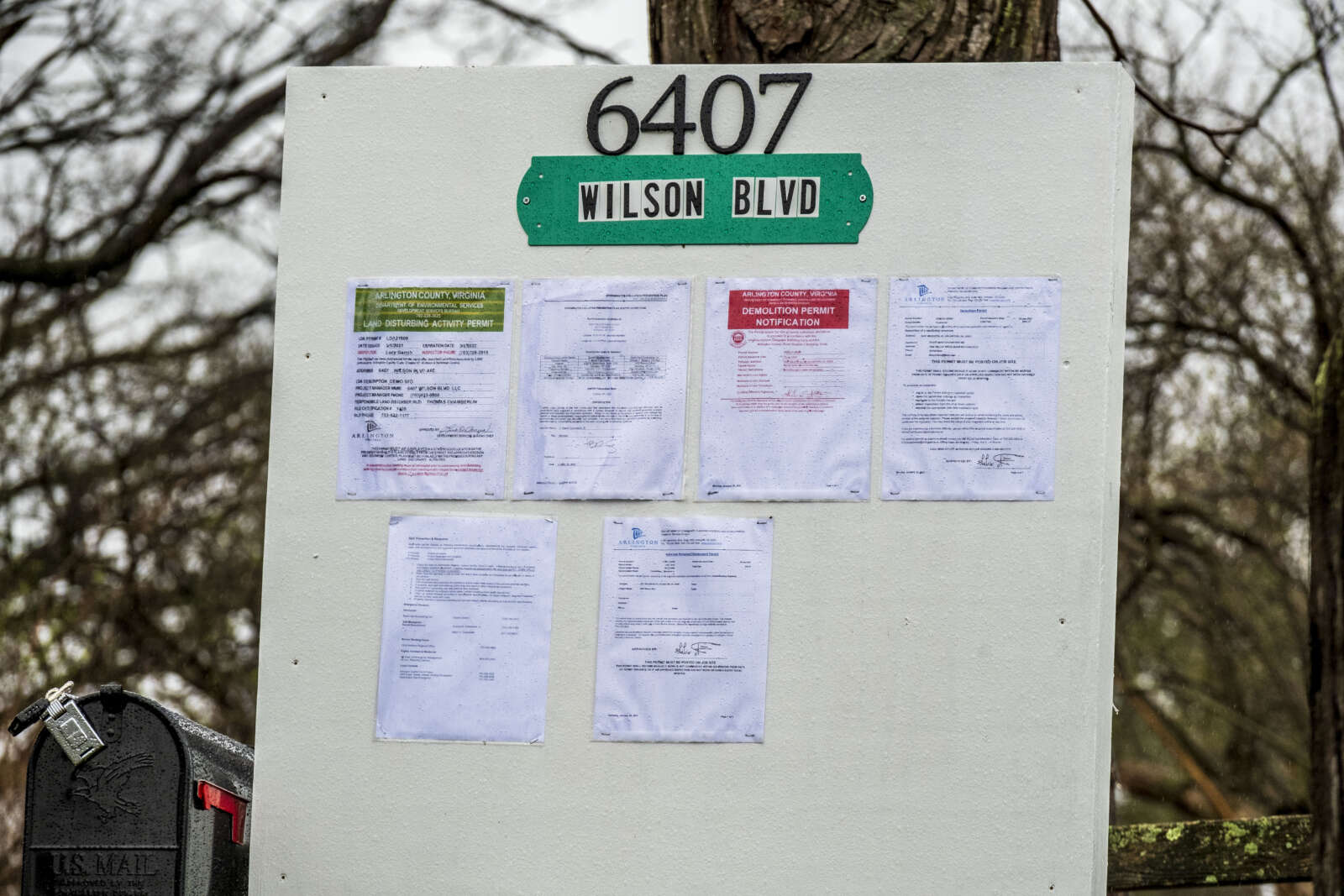

Today, just about the only physical trace of Freedman’s Village is a plaque on a highway overpass. Some of the descendants of that community remain in Arlington today, but for others, exile has been made permanent.

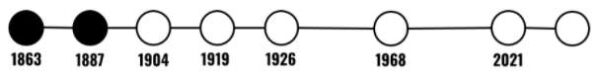

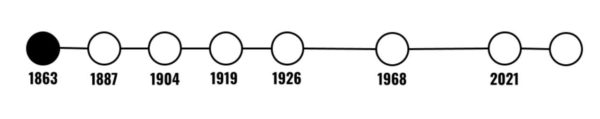

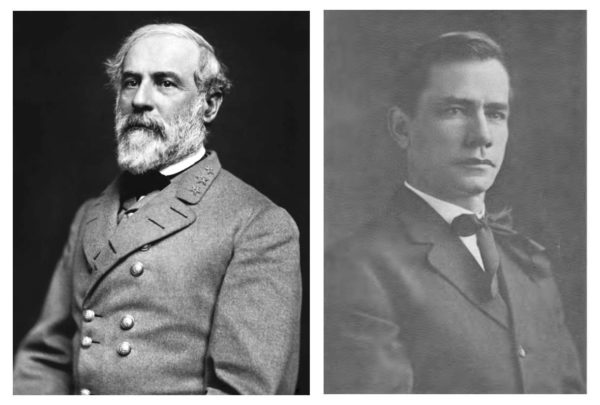

This is the second part of Lyon’s Legacy, a biweekly series on ARLnow (you can read the whole thing, with citations, here). It will tell an eight-part history of how Black people, and other groups that experience racial or economic discrimination, have been excluded from living in Arlington County. Last week, the story started with Freedman’s Village. But with the destruction of that community comes the arrival of Frank Lyon and others who willfully embedded white supremacy into our county’s laws and urban planning.

What those men did is still with us, a century later.

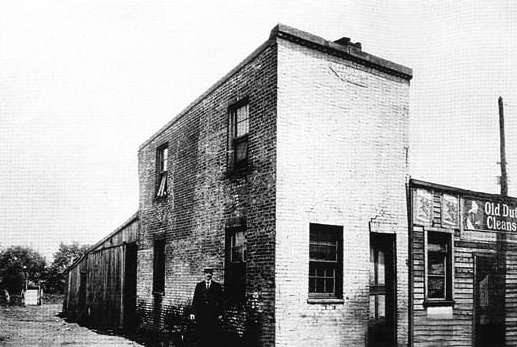

By the 1880s, the county’s white leaders began to agitate against Freedman’s Village. One of Virginia’s U.S. senators called it “improper that government property should be continually occupied by squatters who have no interest in it such as to stimulate improvements.” These ‘squatters’ were residents who had worked to build on the land for a quarter-century, paid rent, and paid municipal, state, and federal taxes of all kinds. But they were Black, and their law-abiding industry didn’t turn a profit for white real-estate developers in the county. The government issued eviction orders at the beginning of winter, 1887. Mt. Zion Baptist Church, like all the other people, businesses, and institutions in Freedman’s Village, had to go.

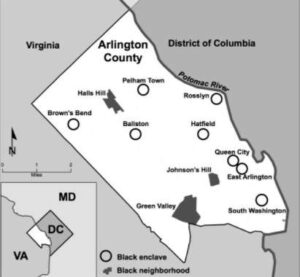

The diaspora of Freedman’s Village took root across the county and beyond. The forbearing evictees settled in middle-class Black communities like Johnson’s Hill, Butler-Holmes, and Green Valley, as well as poorer areas like the farms of Hall’s Hill and the bustling Queen City. Queen City was so egalitarian that some residents later recalled that “a man sometimes didn’t know he was poor until he was 27 years old.” But Queen City isn’t on any Arlington map today. Only fifty years later, the government demolished their homes a second time — not to build the Pentagon, but to build the Pentagon’s freeway exit.

In the late 19th century, the county’s Black community had political power. No fewer than five Black men served on the County Board between 1871 and 1888: William A. Rowe, John B. Syphax, Travis B. Pinn, John W. Pendleton, and Tibbett Allen. Tibbett Allen lost his seat under suspicious circumstances and was replaced by a white Confederate veteran. There were no more Board members of color for a full century afterwards.

After the dispersal of Freedman’s Village, before the turn of the century, there were Black neighborhoods, there were white neighborhoods, and there was Rosslyn. Rosslyn was a residential district inhabited by working-class Black people. They were attracted by the chance to live so close to the Federal jobs across the river, where racial discrimination in employment wasn’t quite as intense.

Rosslyn was also “Dead Man’s Hollow,” a thicket of saloons, gamblers, and sex workers. It attracted white Washingtonian drinkers, too, on the merit of its location: The county was outside the jurisdiction of Washington’s cops, but close enough that a drunk who’d blown his streetcar fare on cards could teeter home across a bridge. And the county maintained a police force totalling two — not enough for a crackdown.

But what made Rosslyn special wasn’t the Black people or the saloons — it was their combination. These saloons weren’t segregated. At least one was Black-owned. These were tables where spades and diamonds meant more than black and white.