Arlington leaders agree that Amazon’s impending arrival in the county demands urgent action to address housing affordability — but there’s a lot less agreement on what sort of policy response is necessary to hold down the area’s skyrocketing housing costs.

Some of the changes officials are envisioning are relatively modest ones, expanding on existing efforts that began long before the tech giant announced its plans to bring 25,000 workers to the area. After all, many have argued that the new headquarters set to pop up in Crystal City and Pentagon City won’t prompt the sort of explosion in gentrification that Amazon’s opponents fear.

Other experts see a need for more ambitious tactics, like allowing more development in Arlington to flood the market with more homes. That could well be a politically explosive change in the county, particularly if it means increasing density in Arlington’s oldest residential neighborhoods.

Or perhaps there’s a need for a more creative approach — some progressive activists are championing the creation of a “community land trust,” a strategy embraced elsewhere around the country to allow for the communal ownership of affordable homes.

It presents local leaders with a series of choices that could well define the county’s destiny for decades. And with Amazon’s workers set to start arriving by the thousands next year, officials won’t have long to make up their minds.

‘We should never let a crisis go to waste,” said County Board member Erik Gutshall. “Amazon is bringing a sharp focus to these fundamental issues, and it’s providing us with the opportunity to double down on the sort of planning we’ve done for decades.”

Building on existing efforts

County Board Chair Christian Dorsey agrees that the urgency of addressing housing affordability has been “magnified” since Amazon’s momentous mid-November announcement.

But, fundamentally, he says “the world, as I see it, in terms of housing strategy is not very different than it was” before officials knew they’d won a new Amazon headquarters.

“We’ve identified the tools we’d like to deploy,” Dorsey said. “Now we have to do the hard work of deploying them.”

For instance, the county has long relied on its “Affordable Housing Investment Fund” to provide loans to developers building affordable homes. Those projects often include apartments guaranteed to remain affordable to renters, known as “committed affordable” homes, that are most valuable for people at the lowest end of the income scale.

The County Board allocates cash to the fund each year, and that contribution has recently hovered around $15 million annually. The county is facing a budget squeeze in the coming fiscal year, but as tax revenue from Amazon’s new properties and workers trickles in over the next few years, Gutshall believes the Board should “earmark some of that specifically” for the loan fund.

Similarly, he notes that the Board will also be able to force Amazon to send cash to the program as it builds new offices (most of which will be located in Pentagon City), as developer contributions are the Board’s main tool for seeding the fund with money.

But as market forces persistently push the costs of new development higher, researchers believe the county also needs to preserve the affordable homes it already has.

“Buying up and preserving existing middle-income housing, that stretches public subsidy dollars much further than trying to build stuff from scratch,” said Jenny Schuetz, who studies housing policy with the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program. “The county should be doing more of that preservation work and they should be focusing on that area near the new headquarters.”

The Board has indeed worked to preserve some affordable homes already by setting up “housing conservation districts” to protect older, “garden apartments” designed to be affordable to middle-income renters. Officials first passed the policy in 2017, with plans to eventually allow developers to replace protected homes with even larger affordable developments, but there’s been little movement on the issue since then.

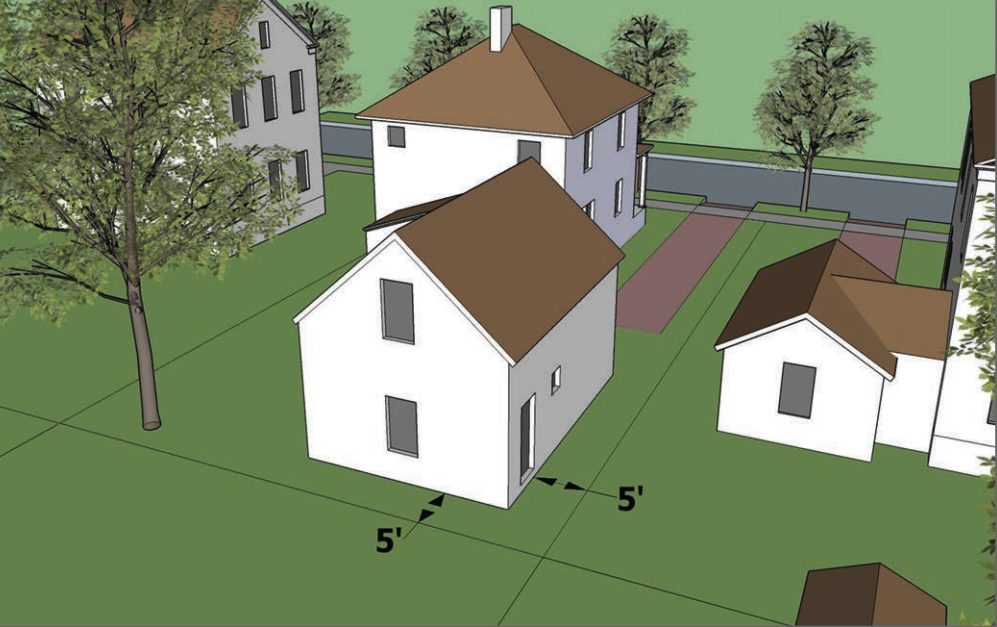

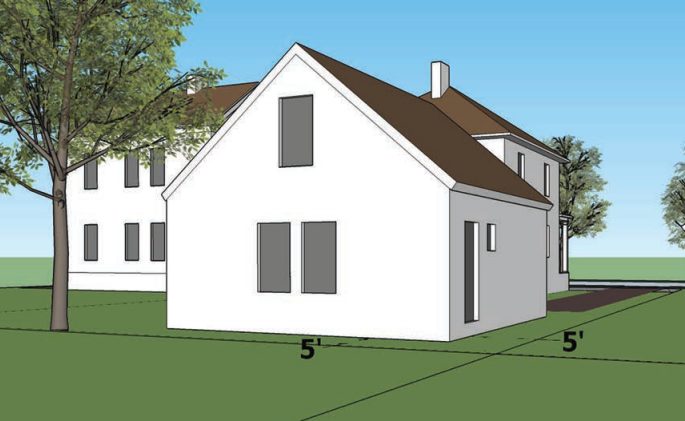

Gutshall argues that the county needs to “accelerate” some of that work, as it seeks to expand “missing middle” housing, commonly understood as homes that fall in between apartments and single-family houses. The Board already loosened some of its regulations for accessory dwelling units, or “mother-in-law suits” on the same property as another home, and Gutshall wants to further tweak zoning rules to allow for more duplexes and small apartment buildings to be built around the county.

“We need to be thinking about how we can keep the character of residential neighborhoods, but still open up housing types and allow for better transitions on the edges,” Gutshall said. “At the same meeting we vote on the Amazon deal, I would love to see a ‘missing middle’ directive… to really identify key areas where think we can make some rapid progress addressing this.”

Touching the ‘third rail’?

Yet the scale of the affordability challenge confronting Arlington has convinced many experts that such changes aren’t enough.

Many observers see a clear and urgent need to ramp up the supply of housing more rapidly, even if that means the construction of the same sort of high-end apartments that are already commonplace in the county. Those homes themselves might not be affordable for low-income renters, but experts argue that any new apartments will have a positive impact on the market as a whole.

“People moving into those new homes come from somewhere,” said Eric Brescia, a member of Arlington’s Citizens Advisory Commission on Housing, who also works as a Fannie Mae economist. “Think of it like the market for cars. A lot of poorer people buy used, not new, at first. New apartments help free up the older stock for people of more modest means.”

But the question becomes where those new apartments will fit, and that leads to some very thorny debates for local leaders.

Anyone walking along one of Arlington’s Metro corridors can see that neighborhoods like Rosslyn and Ballston are already jammed with high-rise developments. Most of the rest of Arlington is reserved for single-family neighborhoods — as much as 87 percent of the county is zoned only to allow for that type of development, according to one recent analysis — but officials might need to reverse that trend as Amazon ramps up the pressure on renters.

“Many people are saying it’s time to look at this exclusive, single-family detached development and how wasteful it is in terms of land use,” said Michelle Krocker, the executive director of the Northern Virginia Affordable Housing Alliance. “But if anything is going to shake communities to their core, this will be it.”

Schuetz points out that these are often wealthy neighborhoods, full of residents “that turn up in large numbers and vote” if they fear encroaching density. But she doesn’t see any choice for the county but examining the prospect of allowing more development in a wider variety of places.

“You have these neighborhoods within a mile, walking distance, of the Metro, but they’re only zoned for single-family homes,” Schuetz said. “It’s just not efficient.”

Dorsey acknowledged that such discussions have always been a bit of “a third rail,” politically, and he understands the impulse of homeowners who might “worry about what more density would look like in their neighborhood.”

“I don’t fault people for wondering if we’re intending for the same density as in Ballston to come to every low-density neighborhood,” Dorsey said. “I get that… that’s why we have to talk about this with real specificity.”

And Dorsey says the Board isn’t considering any sweeping changes to zoning rules across Arlington, even if advocates favor such a move. Instead, he expects a more modest first step is increasing density along some sections of Lee Highway, where the Board is already gearing up an extensive study of its plans for the corridor.

“The potential we have in Arlington is along our major transportation corridors, Lee Highway in particular, where there is more than enough opportunity for substantial amounts of new housing,” Gutshall said. “If we’re able to unlock that, that will carry us through our next 30 to 40 years.”

Following in Bernie’s footsteps?

Beyond these debates about zoning and density, some activists see room for another, very different path for the county to pursue as Amazon looms.

Tim Dempsey has been working with advocates and local leaders on the idea of a “community land trust” since first coming across the idea while reading a bit more about Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) during his 2016 presidential bid.

While he was still just the mayor of Burlington, Vermont, Sanders helped create a land trust, among the first of its kind in the nation. In the unusual arrangement, a nonprofit buys up available land, then builds homes atop it.

Anyone can then move in and pay a mortgage on the homes themselves, while the nonprofit retains the ownership of the land. That protects home prices from wild fluctuations, particularly the sort of speculation that could follow Amazon’s arrival in the county, Dempsey said.

“This prevents the land from falling into a speculator’s hands in the first place,” said Dempsey, who sits on the steering committee for the Sanders-inspired group Our Revolution Arlington

And more than just providing low- and middle-income people with a place to rent temporarily, Dempsey believes this method “allows people to have many of the benefits that come with home ownership, like building equity, tax deductions and having very stable housing.”

“They might not get the full value of owning a home, but they probably would never be able to get into homeownership to begin with, otherwise,” Dempsey said. “This could address long-standing social justice issues when it comes to home ownership.”

Without such a model in place, Dempsey fears Amazon will push already skyrocketing home prices higher and force people out of Arlington. That’s why he’s already brought the idea to many Board members and other local affordable housing advocates, where he says it’s largely earned a warm reception.

That’s significant, because Dempsey believes the county has a key role to play in setting up the trust — the county would likely need to provide the cash to get the effort off the ground, and could take a leading role in acquiring land for any future nonprofit.

Dorsey says he’s certainly willing to examine the issue in more detail. But he urged the trust’s proponents to strive for the true “end game” of such a program, rather than getting hung up on setting up a trust, per se.

“I don’t want to get so focused on the prospect of a land trust that we don’t look for the true essence of this opportunity: how do we acquire property that can be made into affordable housing?” Dorsey said. “It could be a land swap, or allowing an entitlement to build something that’s more dense to get a different opportunity elsewhere.”

Where Dorsey and Dempsey can agree is that such a trust would be most effective if it’s a regional effort.

Indeed, with Amazon’s workers expected to settle all throughout the D.C. area, experts of all stripes are unanimous that Arlington can’t hold down housing prices on its own, no matter which strategies leaders pursue.

“Arlington can obviously play a part in this, but housing markets are regional,” Brescia said. “And we need more collaboration across the region.”

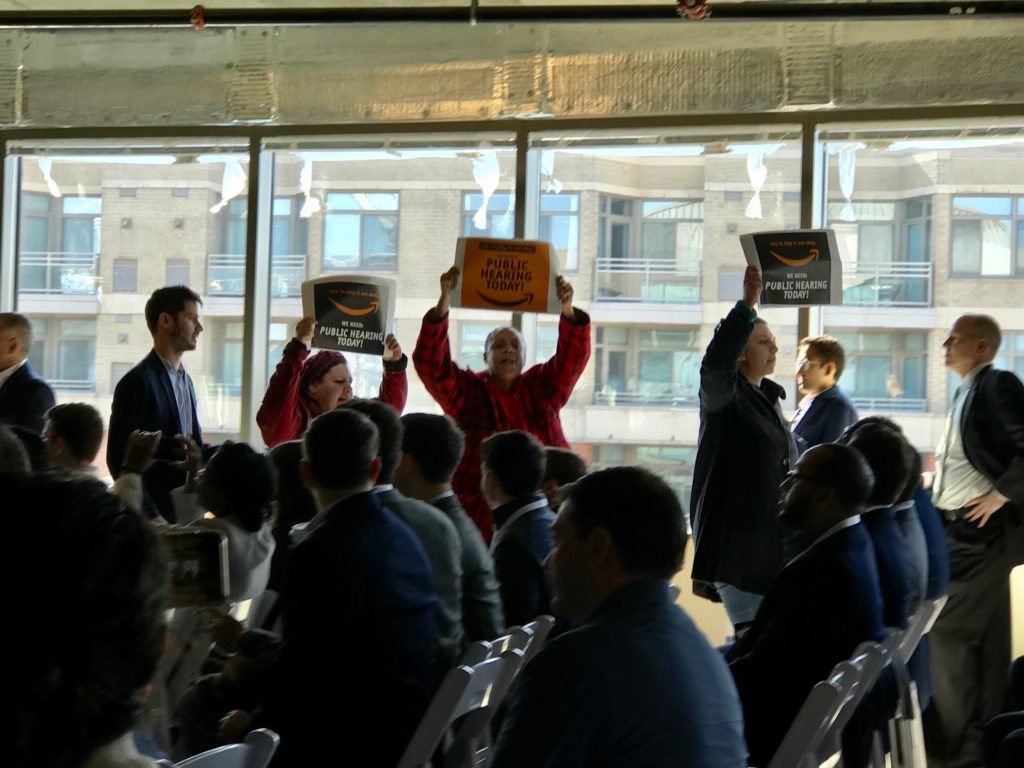

File photo