Police Looking for Missing Teen — “ACPD is seeking assistance locating 15-year-old Alejandro… Described as a Hispanic male, 5’8″ tall, 145 lbs with brown eyes and half yellow/half black curly hair. He has ear piercings, a nose piercing and wears a silver dog chain necklace.” [Twitter]

Another Missing Teen — “ACPD is seeking assistance locating 14-year-old Anderson… He is described as a Hispanic male, approx 5’7 tall and 130 lbs. Last seen wearing a black sweat shirt, gray pants and black sneakers. He is known to frequent Rocky Run Park and CVS (2121 15th St N).” [Twitter]

W-L Name Change Attorney Disbarred — “A Virginia state court has disbarred Jonathon Moseley, an attorney who has represented a slew of high-profile Jan. 6 defendants, including a member of the Oath Keepers charged with seditious conspiracy, as well as several targets of the House select committee investigating the attack on the Capitol.” Moseley also represented opponents of changing the name of Arlington’s Washington-Lee High School to Washington-Liberty. [Politico, ARLnow Comment]

Another Drug Take-Back Day Planned — “On Saturday, April 30, 2022, from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., the Arlington County Police Department (ACPD) and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) will provide the public the opportunity to prevent pill abuse and theft by ridding their homes of potentially dangerous expired, unused and unwanted prescription drugs. This disposal service is free and anonymous, no questions asked.” [ACPD]

Fmr. APS Superintendent Leaving WV Job — “Among 75 personnel transactions during Monday night’s Berkeley County Board of Education meeting, district Superintendent Dr. Patrick K. Murphy announced his retirement, which was unanimously accepted by the board along with the other movements.” [The Journal]

Historic Home Reopens — “The Ball-Sellers House, one of the few surviving examples of working-class 18th-century housing in Northern Virginia, reopened for the 2022 season on April 2. Owned and maintained since the 1970s by the Arlington Historical Society, the house will host a number of programs in 2022.” [Sun Gazette]

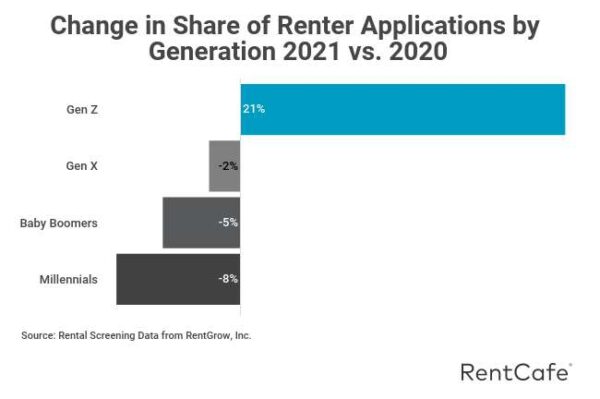

Nearby: MoCo Wrangles Over Housing — “In the D.C. region, where local governments are struggling to address a severe housing shortage that is driving up prices, elected officials are under growing pressure to push back against civically engaged homeowners who mobilize against new housing construction. Montgomery County, an affluent D.C. suburb that has experienced transformative growth and demographic change in the last 30 years, exemplifies how hard that can be.” [DCist]

It’s Thursday — Rain throughout the day, until evening. High of 56 and low of 48. Sunrise at 6:45 am and sunset at 7:39 pm. [Weather.gov]